I have often mentioned Education for Ministry (EfM) as one of my passions. It’s a four-year study of Old and New Testaments, church history, and theology. It’s designed to be like a seminary for lay people, although priests and deacons may serve as mentors or even as group members. The basic design is to give participants insights, information, and ways of doing things that will assist in their doing their ministries, both in the church and out in the world.

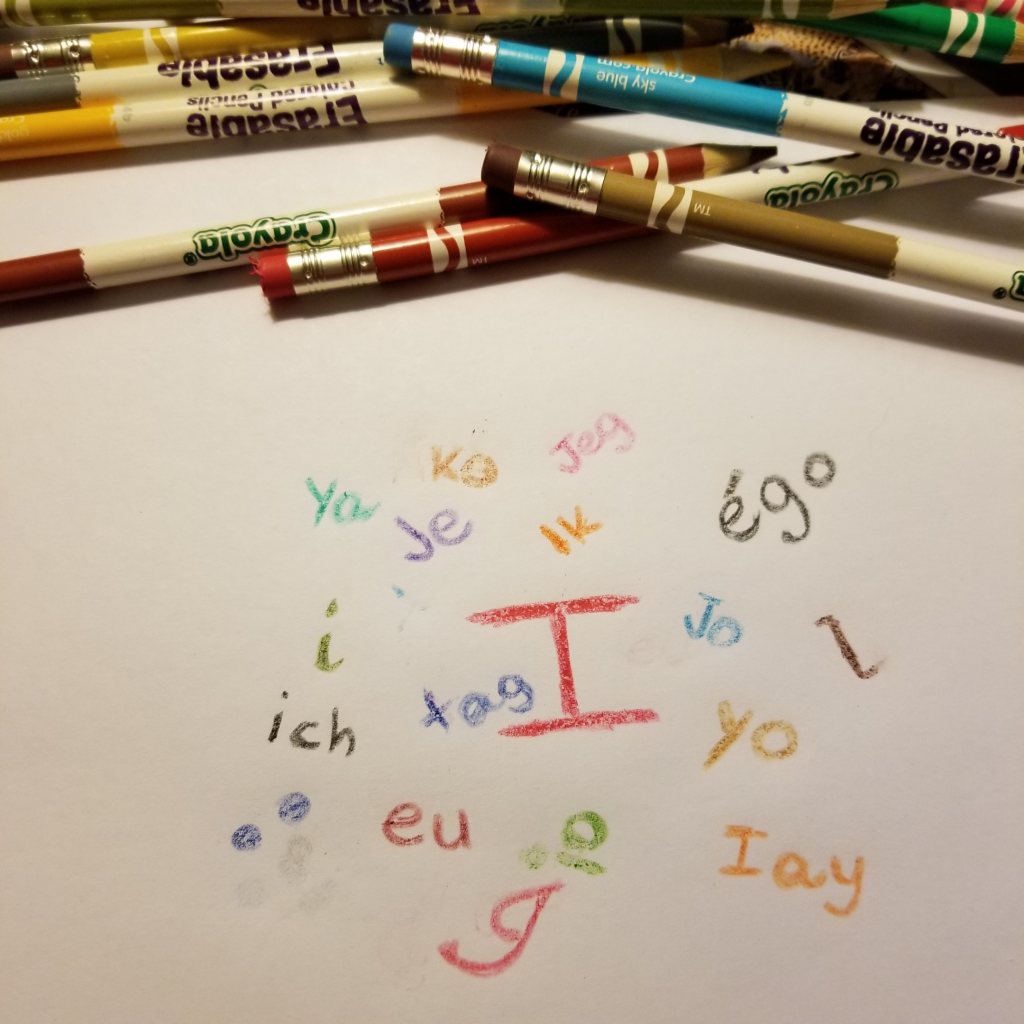

One of the disciplines or practices on which we’ve been working hard for the last few years is the use of the “I” statements. “I” statements are used to indicate our personal beliefs, thoughts, opinions, and positions, as opposed to “we” statements which lump us in with others who may or may not share our thoughts and beliefs. It takes away, to an extent, the “us” or “we” and “them.” It’s like the difference between the words of the Apostles’ Creed vs. the Nicene Creed. Both are statements of faith and belief, but one uses the singular pronoun while the other uses the collective or plural form.

Using an “I” statement is often seen, at least in contemporary culture, as a sign of ego; “I have done this,” or “I have got that.” Those are statements of accomplishment, like patting oneself on the back by saying it aloud so that others will know just who it is they are dealing with and why the speaker deserves attention or admiration. The ego demands, no matter how gently it slips into a conversation. When someone is very forthright in using the word “I,” especially when directing others or expressing their opinions and thoughts as the only truly right ones, is where the problems exist. In essence, the ego is saying “I am important; you are not.”

A better way to use “I” is to use it as a way of communicating through allowing a person to express how words and actions make them feel without casting any aspersions on the person to whom they are speaking. “When you say this, I feel that.” It works very well as a bridge to civil discourse as opposed to finger-pointing and increased anger.

Our late mentor and friend, Ann Fontaine, was quite a proponent of the “I” statement. She was not afraid to remind us that we were to use “I” statements rather than “we” statements because we could not with any assurance speak for the group or members of the group. It was owning our own stuff, and not trying to either force it on someone else or point to someone else as if they were personally a protagonist. I’ve tried using it with friends, and it’s created much better conversation since the person to whom I’m talking does not feel like I am pointing them out personally. Ann was never afraid to remind us when we slipped into the “we” speech, as we do on occasion. In our sessions, at some point, someone will mention they feel like Ann’s tapping her foot at our forgetting. We laugh, and we restate our words and phrases to reflect our individual points of view or feelings. It’s almost like having her back with us.

Jesus was particular about what he said. He was not afraid to make “you” statements, especially with his disciples. They asked why they could not cure someone, and Jesus would give them an answer that indicated that something was lacking but without using a lot of judgment calls or name-calling. He wasn’t afraid of using names, as he had been known to call the temple officials “brood of vipers” and other choice epithets. Still, he didn’t use the word “I” except when speaking to others of his beliefs, his knowledge of God, and his presence in the world. “Verily, I say unto you” usually was a turn of phrase that he used when correcting something from Scripture that had been misinterpreted. Still, he wasn’t pointing fingers directly at someone and accusing them. Instead, he was making a statement that called attention to the fact that there was something that needed to be corrected.

“I” statements aren’t necessarily wrong. Some wag once said words to the effect of if you don’t blow your own horn, it won’t get blown. There are times these days when the ego wants to come out, to be stroked, and to let others know what valuable words for commendable actions the speaker has performed but of which the audience would have been unfamiliar. Some war heroes never speak of their acts of bravery and go to their graves without ever having mentioned them. Very possibly, there were those for whom the memories were too painful, but many remained silent because they considered they were doing their job, and their job was protecting others.

I found that using “I” statements in terms of making another person aware of how I feel when they say or do something is much less confrontational than pointing fingers and calling names. It’s like making a confession where the focus is on the sins I have committed and not something that someone else has done to me. Yes, people have done things to me that I have difficulty forgiving, but my confession is how I react to those things, not a condemnation of the actor. It isn’t my job to take someone else’s inventory, as the 12-Step programs emphasize, but to own my own thoughts, beliefs, feelings, emotions, actions, and shortcomings.

If you wonder why so many of my reflections use “I” statements as a basis or foundation, there’s the reason. I work hard to use it. It is how I see and feel and think, even though I may bring in the thoughts and words of others. In conversation, I have to pause before saying something so that I can speak of how another’s actions and beliefs affect me. I take time to phrase it so that it’s not confrontational but rather merely informative.

If you haven’t tried it, do give it a shot. And whether or not you ever knew Ann Fontaine, and many of you have heard of her or knew her, remember to say thank you to her.

God bless.

Image: I image.jpg, Author’s interpretation

Linda Ryan is a co-mentor for an Education for Ministry group, an avid reader, lover of Baroque and Renaissance music, and retired. She keeps the blog Jericho’s Daughter. She is also owned by three cats.