The Anglican Communion is a wonder of balance, even though sometimes we seem like the Pushmi-Pullyu two headed beast of Dr. Doolittle’s Zoo. Not too Roman Catholic, not too Protestant. We love our sayings, such as “All may, none must, some should,” a perfect reflection of our theology, liturgy, and just about everything else.

The Daily Office readings leading up to Advent have been mostly pretty grim. The occasional flights of heartbreaking beauty in the vision of the throne of God in Revelation. But then there is Judgment Day, and the whore of Babylon. Even stripping “her” from the misogamy and saying Rome or the greedy world of today, it is still pretty nasty. The Old Testament lesson has been focused on wars and the struggle to regain Jerusalem after the exile, but also dire warnings about obeying every jot and tittle of the 613 commandments of the Jewish law. And the parables chosen tend to be the opaque ones.

This can bring up a lot of difficulty for a contemporary reader, especially for us liberal, peace and justice, gender equality, tree hugging Episcopalians. How can we resolve all those laws when even Jesus, the bringer of the new Covenant, has a few, and not easy ones? Spread the Good News? Obey the Laws? Love and forgive? Punish those who stray? Faithful to Scripture and the Faith? Interfaith acceptance? Pushmi-Pullyu. Who are we? And how can we resolve this dialectic, honoring both sides? Then I came on two men from our own history that for me, at least, pulled it all together.

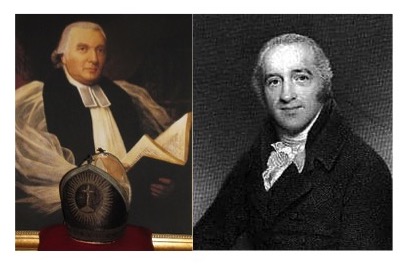

There is no holy person for Nov. 13 in A Great Cloud of Witnesses, but like our church, this day in the middle is bracketed by days for Charles Simeon, Priest (1759-1836) on Nov. 12, and Samuel Seabury, Bishop (1729-1796) on Nov. 14. Bear with me through this history lesson.

At Cambridge, the Rev. Charles Simeon was deeply troubled by his belief in his unworthiness to properly receive communion in purity of mind, body, and spirit. Like Martin Luther before him, and many others, after suffering and wrestling, stuck in his piety, he experienced a shift in his understanding of the Presence on the altar and its efficacy, realizing that neither the law nor any person’s act of piety could make them worthy. It was the sacrifice of Christ and faith alone that bestowed grace. It was a gift, not something to be bartered for. From that one insight he dedicated his life to the evangelical movement of the Anglican Church, a founder of the Church Missionary Society (publishers of A Great Cloud of Witnesses, which makes his inclusion twice as nice). As rector of Trinity Church, Cambridge for 54 years he was a passionate and extraordinary preacher, his simple Biblical sermons spreading notions of evangelical and clerical pastoral service still part of our tradition today.

Bishop Samuel Seabury was the first American bishop, and without bishops the American Anglican Church was tied to England to make new priests and bishops. That got messy when a group of rebels decided to go to war with England, and we know how that worked out. Seabury was loyal to England throughout the Revolutionary War, and served as a chaplain for the British army. However, after the war he remained in the new country and accepted American citizenship. At a secret meeting in Connecticut in 1783 he was chosen to try to obtain Episcopal Consecration. But since he could no longer swear fealty to the English crown some other way had to be sought. Our church sort of sneaked its way in through the back door. In Scotland there were bishops called Non-juring bishops, those who refused to swear allegiance to England. Through them Seabury was made bishop in Aberdeen November 14, 1784, and then was able to establish an independent Episcopal Church in the U.S. He also agreed to adopt the Scottish Book of Common Prayer of 1764. What makes this more than an historical footnote is that the Scottish liturgy was far more focused on the Eucharist and used prayers more coherent with the historical Church of both the East and of Rome then did the English prayer book of 1662. Of note was the restoration of the epiclesis, the invitation to the Holy Spirit to come down on the elements and on us during the consecration of the Body and Blood. As our Presiding Bishop Michael Curry pointed out last week from Aberdeen, Scotland, the Scottish Church is our Mother Church.

What this history lesson offers is a look at the two sides of our spirituality, evangelical and canonical. And the two sides of those messy lessons. There is a canonical duty of obedience to priests and bishops, as there is to the laws set down in scripture. We all fall under those, whether we know or observe them or not. It anchors us. But there is also the movement of the Spirit in preaching and the call to evangelical conversion. There we are again, betwixt and between. By faith, perhaps balance.

I don’t discount the warnings about eternal damnation, just as I cling to the presence of the Spirit which I experience in prayer and in the Eucharist. A forgiving God who will save all those who will come to God. But we have that choice. Even in the eschatological moment of Revelation, there will be those who won’t turn and kneel and open themselves to whatever change they couldn’t make in life, to be made perfect in the Blood of the Lamb, to allow God to wipe away every tear. As there will be those who have been practicing their whole lives to embrace that Glory. So I am content to live in the tension between holy obedience, as Jesus showed us, and the freedom to find our way, fall, get up, pray, redirect, and go on our messy way, the gift of choice which Jesus also showed us.

And we are blessed with the presence of such a Cloud of Witnesses in our Church Triumphant who can still teach us so much as we fumble along on our way to heaven.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is a parishioner at All Souls Parish, Episcopal, Berkeley, California and earned her master’s degree and PhD from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.