There is a terrible irony in today’s Gospel, Matthew 27:24-31. The very actions we use to keep us alive are here actions of death. The Sanhedrin and Pilate wearing their masks of righteousness. The powerful keeping their distance to the real needs of the people. And hand washing. To quell a riot, Pilate washes his hands. What he says, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves,” has been used as an excuse to blame the Jews for Jesus’ death, and caused the death of only God knows how many Jews in the past two millennia. And we know that the Matthean Jewish community was in conflict with the remnant of the Temple Jews, the kind of elders and pharisees who did bring Jesus to trial. Pontius Pilate was not a nice man, and he certainly didn’t like Jews. Or being sent off to govern this dirty nasty foreign backwater. Both Philo of Alexandria and Josephus, two first century Jewish historians, had some pretty harsh words for Pilate. That is the historical perspective. But there is more to mine in this reading.

And so Pilate releases Barabbas, a known rebel and enemy of the Roman occupation, rather than the rather mild mannered, weak, and of little consequence Jew from Nazareth. It really doesn’t make sense in terms of politics. The name “Barabbas” itself is odd. It is a patronymic for “son of the father.” Isn’t that who Jesus claimed to be? Coincidence or not, let’s move on. This appeased the crowd, who wanted a war leader for a Messiah. And, in truth, even this rebel had friends and a mother who were glad to get him home, free from that terrible Roman execution on a cross. We sometimes forget about the humanity of these minor characters in this cosmic drama.

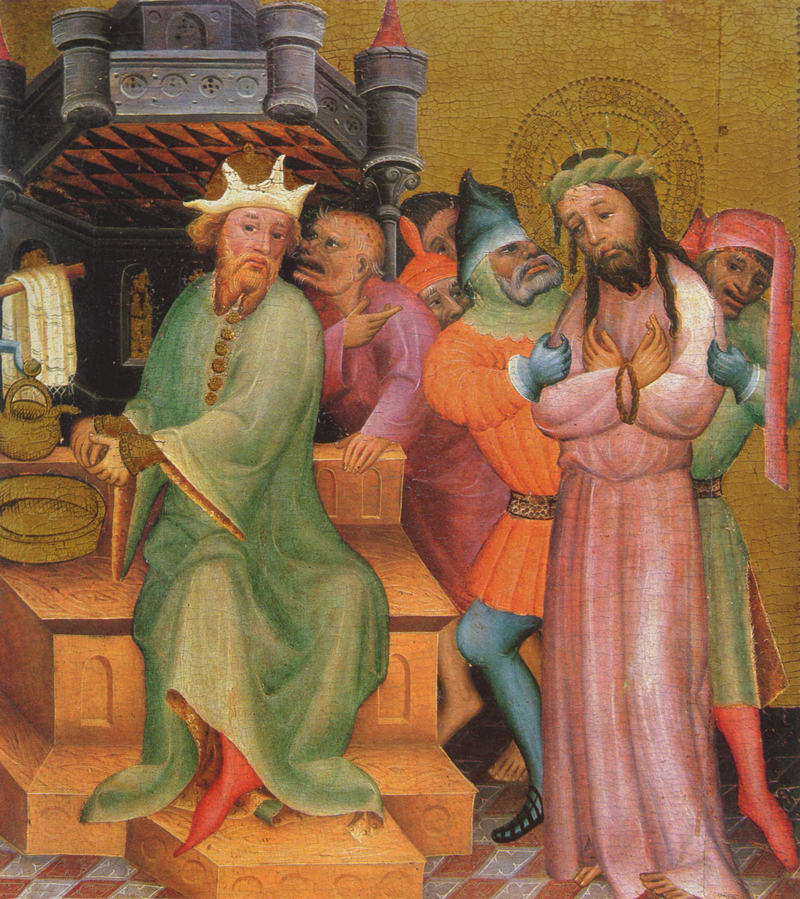

And so they took Jesus to the governor’s headquarters at the praetorium, probably the Antonia Fortress. And soldiers are not nice with prisoners. If we have any doubt about what the powerful can do to the vulnerable, I suggest watching the news and the out of bounds behavior towards peaceful protestors. There is something nasty in human nature. It comes out in bullies. In those in authority, from kings and governors to parents and bosses. Hit the helpless. Make them cringe. Cry. We have tried to domesticate sadomasochism with safety words and fanciful leather costumes, but, at the heart of it, it is cruelty played out on another person’s body and soul. And it is part and parcel as much a part of police brutality today as it was in that garrison in Jerusalem on that day so long ago.

To be clear, I am not making a partisan statement. I don’t support liberal violence or conservative violence. I follow Jesus. I pray for friend and enemy. I do not consider those who in love and mercy have different opinions to be enemies. Peaceful discourse is good. Beating innocents is neither peaceful nor good. And history is so full of massacres and genocides that we weep with Jesus far too often. The death marches forced on Native American tribes, the genocides in Africa between the Tutsis and Hutus, the elimination of the Uyghurs in China and the Rohingya in Myanmar, the horrors of the Serbian/Croatian conflict. And the systematic round up and elimination of Jews, gays, political protesters, and Gypsies/Romani in Nazi Germany. Humans killing humans in wholesale, dare I say, glee. And now today in our cities. Yes, we are a sinful people. Those soldiers had mothers and sisters. They must have mourned their brothers-in-arms lost during deployment. But here they are, mocking, beating, humiliating a poor Judean peasant with some odd religious ideas. And apparently enjoying it. What a great story to retell over a mug of cheap wine with the guys. When we say we are an incarnate people, what is happening to Jesus in this reading stands out in full color of what we are and who our God is. Jesus didn’t just sit under a tree or in a portico with his students and tell spiritual stories until his death at a ripe old age. Our God incarnated into the muck and sorrow of our sin, and from there he brought us back to life and light. It was the hard way. It was the Father’s way. It was Jesus’ way.

Paul’s closing of his letter to the church in Rome (Rom 16:1-16) reads like the parish prayer list. Interesting names. Not much else. But look, when he says, “Greet Rufus, chosen in the Lord; and greet his mother—a mother to me also.” That is tender. That is loving. That is intimate. That is the opposite of the horror of the scene in the fortress. That is the love of God, the Spirit in Paul reaching out with consolation and blessing. The question is what turns people like those of the church in Rome into a violent mob, or women and men sworn to protect into the cruel arrogant sadistic legionaries beating, mocking, and spitting on Jesus? If I had a quick answer, I’d give it. Embedded social expectations? Demons? Probably both. I’m pretty sure it has something to do with power, and the entitlement which power grants.

Perhaps a clue comes from the reading from Joshua (Josh 24:16-33). Just before his death, Joshua gathers all the tribes of Israel before him, and reviews how they got from Egypt to this land they fought for and claimed, as the Lord commanded. And he exhorts them one last time. You cannot serve the Lord and other gods. This God is jealous and powerful. And so they agreed and sealed their vows with a covenant, a book of the Law, and placed a sacred stone by an oak tree to remember. (We shall not go into the symbolism of a rock and tree being the very symbols of the high places later forbidden. That is another story for another time.) The lesson we can apply to the soldiers and the church in Rome is that people are formed by their god, or ruler, or law. The soldiers were formed by the symbol of the Emperor, who was the soul, the genius in Latin, of the Roman state. That is why he was called a god. He was a god of power and gain. The people of Israel were ruled by the Lord God, but bound up in the Law. The new churches were ruled by the very nuanced and difficult Way of Jesus. And that required patience, forgiveness, and mutual love.

If that is so, who is our God? Saying it is God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit does not make it so. That is why conversion stories about Roman officers are so important, starting with the conversion of the centurion at the Cross (Luke 23:37) who glorifies, not his emperor, but God as Jesus revealed. These men turned because something beyond their culture and entitlement called them to a greater and truer reality. That is the God whom we must follow. And any police officer or military officer or Roman officer who is faced with following their oath to that profession or following their vow to God in baptism is standing at the Cross, not in the garrison with a whip. Theoretically, the US Constitution does seem to require an unbiased application of the law, but that is not always the case. The covenant with God, God’s will, is always the case. Perhaps the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and how many more, may have been the catalyst for action focused on systemic racism and the legacy of Black slavery in the U.S., but the sin it exposed runs deeper and has been with us always. And once again we are called to turn from being seduced by the power of violence to turn towards the peace of God.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is at Church of Our Saviour, Mill Valley, CA. She earned her master’s degree in systematic theology from the Jesuit School of Theology/GTU and PhD in church history and spirituality from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California. She lives with her cats, books, and garden.