Election season means a renewed interest in wages and inequality, but are we hearing real solutions to poverty, or just sound bites and buzzwords?

Matthew Desmond, Harvard sociologist and author, addresses poverty through housing costs in his latest book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, and in two articles published in the New York Times and the New Yorker. Desmond blames housing costs, which rise faster than wages, and which can compound with legal fees, eviction processes, and inadequate safety nets, to quickly wipe out savings, leaving many homeless and impoverished.

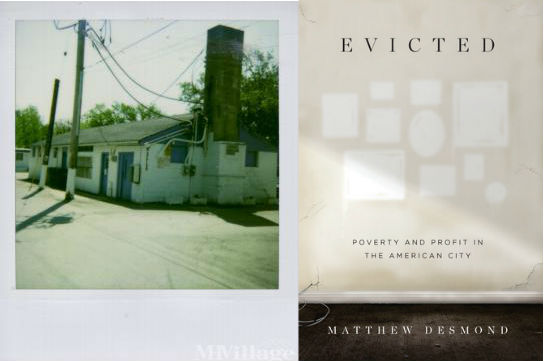

Writing in the Times, Desmond shares the story of a former neighbor, Larraine, and the trailer park they both lived in on the South Side of Milwaukee. The trailer park was referred to as an ‘environmental biohazard’ by city inspectors for the sheer number of code violations it had, but rent exceeded 70% of Larraine’s income each month.

Larraine, a 54 year old grandmother on disability, lived on $5 a day after rent and utilities, and was eventually evicted; everything Larraine owned ended up in a dump. The rent she paid contributed to the half-million annual her landlord netted from a dilapidated and squalid living environment. Evictions led to more profits, and he employed unusual contracts which oftentimes left him with the mobile homes that had belonged to the tenants, which he would then rent to a new family.

Desmond puts the total cost of preventing these evictions–and squalid living conditions–around 22 billion per year. Most of our housing assistance, however, is tied up in homeowner tax benefits, which reward more affluent people who already own homes.

From the Times piece:

We have the money. We’ve just made choices about how to spend it. In 2008, the year Larraine was evicted, federal expenditures for direct housing assistance totaled more than $40 billion, but homeowner tax benefits exceeded $171 billion, a figure equivalent to the budgets for the Departments of Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security, Justice and Agriculture combined.

In his New Yorker piece, Desmond shares the stories of other families who are perpetually evicted, and the landlords who call the lawyers. Forced Out shows how cyclical eviction is, and how minor mistakes and setbacks can result in huge, self-perpetuating, economic challenges for impoverished families. His main focus is on Arleen, a young mother, and her struggling family. As a young woman, Arleen left public housing, thinking she’d be able to make it on her own. When she lost her job and fell behind in her rent, she discovered she couldn’t return to public housing, and her cycle begins.

From the New Yorker article:

If Arleen wanted public housing, she would have to save roughly six hundred dollars to repay the Housing Authority for having left the subsidized apartment years before without giving notice; then wait two to three years until the list unfroze; then wait another two to five years until her application made it to the top of the pile; then pray that the person with the stale coffee and the heavy stamp reviewing her file would somehow overlook the eviction record that she’d accumulated while trying to make ends meet in the private housing market on a welfare check.

The heart-breaking piece alternates between Arleen and her landlord, Sherrena, telling two different but very similar stories of costs, bills, and pitfalls that keep amassing despite the best intentions of all parties.

Desmond’s central thesis is that housing costs, and the legal fees and penalties associated along with the lack of support from government agencies, combine to keep the poor poor, regardless of good intentions or hard work.

Did the two articles change anything about the way you view poverty? Were you able to relate to the experiences of Arleen or Sherrena? Evicted is available from Penguin Random House.

Photo of the trailer park referenced in New York Times article / cover of Evicted