by Leslie Scoopmire

Daily Office readings for June 21, 2017:

Yesterday, my friends Andrew and Maria and I were blessed to go on a retreat with our bishop as the day of our ordination to the priesthood draws near. One of the things we did was to go over the liturgy for the ordination of a priest. We carefully examined and discussed the language that is used in the liturgy, because, as Bishop Smith reminded us, words matter. This may seem to be an obvious point, but this is actually a statement that receives a lot of resistance right now, especially in our political discourse. As a former English teacher, the idea that words do NOT matter is actually puzzling, and even a bit frightening. As a former history teacher, I recall times when words have been used to the great benefit of humanity. I have also known of times and places where political leaders have used words to inoculate themselves as they have gone about perpetrating great evils, where words have been used to insert terrible concepts into the political discourse through the use of euphemism and doublespeak and sometimes the outright undermining or subversion of the power of words.

No, I believe that words matter. And so do most of the world’s great religions: in Islam, the only Qur’an that can be called a Holy Qur’an in one that is written in Arabic, the language of Muhammad, and a person who has memorized every single word of the Qur’an is called a hafiz, which means “guardian.” For generations, the Torah existed in through memorization. Now, there are actually two Torahs, the written Torah, which we see preserved in the first five books of the Christian Bible, and the oral Torah, which is commentary and explanation about the written Torah preserved in the Midrashim and the Talmud. In the book of Genesis, both Jews and Christians are reminded that God spoke creation into being, commenting on the goodness of creation aloud at the end of each “day.” In the Christian gospel of John, the Word of God is described as being present within creation itself, and Jesus is identified as that living Word.

Words matter.

That’s why my attention was caught when I saw that the Pentecost event in the Book of Acts was one of the readings used today in the daily office. In the reading from Acts 2:1-21, we ar reminded of the power of words in the response of the disciples after the power of the Holy Spirit comes over them, giving them the gift of language. In a blink they are outside, in the streets, doing exactly what the disciples were told to do in our gospel reading—they are out in the world, testifying to the power of God as revealed in Christ to the people they encounter there. It’s probably the most excitement you and I have ever heard coming out of a church meeting.

In a kind of reverse of the curse of the Tower of Babel, now these disciples, many of them simple country folk, have just learned to speak other people’s language. I think that’s an important point for us too in the Church today: we are called to speak to people in their own languages first, rather than expect them to immediately understand the language of Christianity.

Through the power of the Spirit, we are reminded that language is power, empowering us to carry the gospel of Christ throughout the farthest reaches of the world as disciples, evangelists, and teachers—as Christians who are the Church.

But the disciples’ first new language came as a challenge even earlier, for them as well as us. As soon as those early disciples answered Jesus’s call to follow him, they had to learn the language of Jesus—a strange language, then and now, awash in a grammar of grace rather than a grammar of vengeance.

We are still learning Jesus’s language of reconciliation today. It is the language of salvation, but not salvation for selfish ends. Rather, this language calls all disciples, them as well as us, to find the vocabulary for helping to repair the world and our relationships within it, with each other and ultimately, with God. This idea of responsibility of faithful people to repair the world is what our Jewish brothers and sisters call tikkun olam—the repair of the world.

This language was filled with strange ideas, in which the greatest is the least, the least is the greatest, in which forgiveness and grace are more important than being right or self-righteous. Even after Jesus’s life on Earth was done, we can see that the disciples were still trying to make sense of that language. And we are too. We ourselves as Christians 2000 years later also continually work at acquiring that same language– and it’s still just as alien and difficult for us as it was for them. The power of the Holy Spirit is here to help us continue learning Jesus’s counter-cultural grammar of grace and reconciliation.

The Spirit hovered over the waters at creation, and God spoke goodness into the world. The Spirit breathed the Church to life at Pentecost, and blew those disciples out into the streets with the explosive power of love and truth to proclaim the good news to those who most needed to hear it—and in their own languages. The Spirit hovers over us even now, hoping to reinforce the goodness in our hearts. The Spirit is always trying to speak to the soul, using a language that we understood instinctively in childhood, but often have allowed to slip away as our hearts sometimes harden and we become more “worldly-wise.” That’s why the language of love that God imprinted on us at creation, during Jesus’s ministry and again at our baptism, often seems like a foreign tongue. It’s hard for us to trust in words like “grace,” “mercy,” and “forgiveness” for ourselves as being real, much less for us to speak and live them out to others.

But that’s exactly what we are called to do as the Church. We are called to speak to the soul of each precious person we encounter, and hear the echoed whisper of that goodness and love vibrating from them—especially when it’s hard for us to do so, when we allow our differences, our fears, or our suspicions to divide us rather than strengthen us. Words do matter when we are speaking to the soul, and the word is God and the Word is with God and with all of us.

Leslie Scoopmire is a retired teacher and a transitional deacon in the Diocese of Missouri, and a graduate from Eden Theological Seminary in Webster Groves, MO. She is Interim Youth Missoner for the Diocese of Missouri, and tweets daily prayers and news of note @Scoopexplainsit. Her blog is Abiding in Hope.

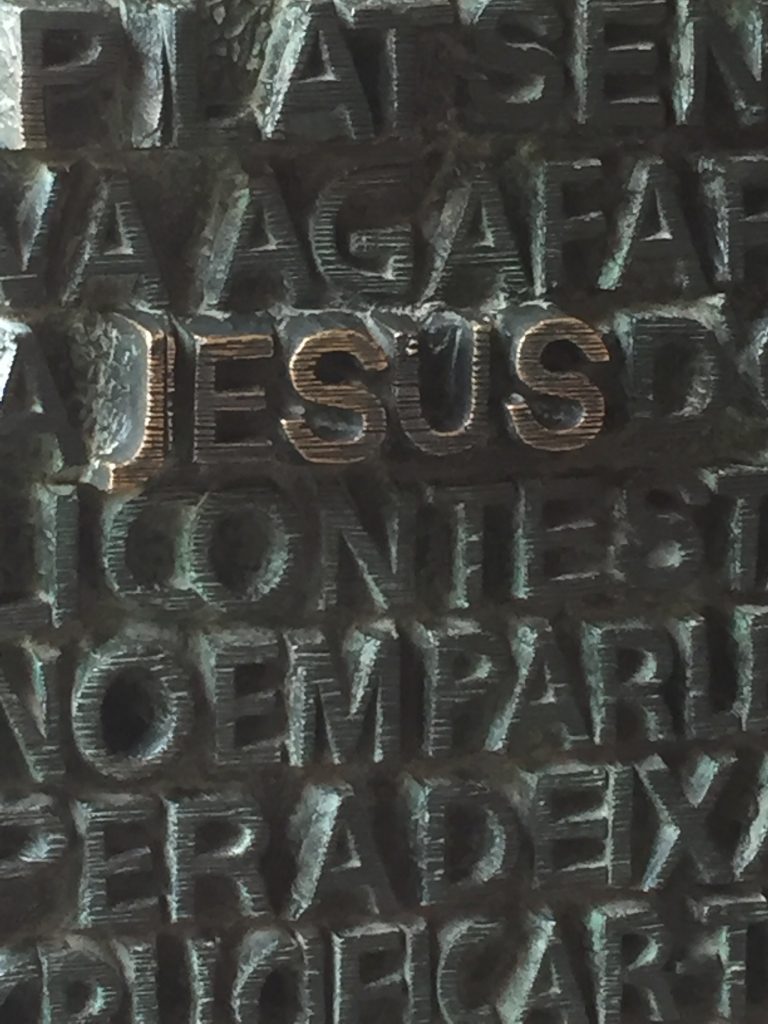

Image: photo by Leslie Scoopmire -Jesus, the Word- detail from a door at La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona