Bill Carroll

Lord, to whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life. (John 6:68)

We live in an age dominated by images. Images come to us unbidden, on screens large and small. We are bombarded with them. And powerful forces, commercial and political, use them to manipulate us. We live also in an age of many words. Words used to distract and control us. Too many words to hear God’s voice. We drown God out with chatter. We dare not speak the risky words that lay our hearts bare—words that lead to genuine fellowship and communion.

Even the language of friendship has been debased. We use “friend” as a verb, friending and unfriending strangers—and others we hardly know. Who would “unfollow” a real friend, just to keep the peace? We live in a torrent of words and shallow relationships. In the world around us, people are all surface and no depth—all more or less expendable. If it were not for communities like the Church at our best—with real friendships and a hunger for God—we would be isolated and alone, sharing everything yet saying nothing.

A famous article (and then a book) once contended that we are living at the end of history. If we believe the hype, there is no alternative to how things are and evermore shall be. We are past the time of historical change, whether revolutionary or gradual. We are off far from home, living on nostalgia—living also in the eternal flux of diversions and memes, beyond all sacred stories, where all is said but nothing is real—where good things come from Walmart or with a click for those with money, and the Kardashians pass for news.

And yet, those who follow Jesus have met the Word that lives in God’s own heart—now also in our flesh. He has spoken the words of life to us—face to face—and he has made us God’s children.

Words can wound us or heal us. They can give us life—or else take it away. They can summon us to struggle for change, or they can numb us and beat us into submission. And so, we are hungry for the words of life.

We speak such words to our children, who become themselves by hearing our words. By speaking, we nourish or stifle their growing sense of self and agency. We speak words of life to those we love, who need our words like bread. We speak words of life to all who depend on our kindness and acceptance—who need our strength and compassion to make it through the day.

If we’re honest with ourselves, we know we’ve spoken words both of life and of death. Most often a mixture of the two. And sometimes, it’s true, our words make a difference. Sometimes our words help somebody put one foot in front of another and keep on living. At their most powerful, our words can even change lives and create new facts on the ground.

Jesus and his fellow Jews would have known the prophecy of Amos, written some 780 years earlier, in the eighth chapter of the book that bears his name. This is what Amos says to God’s People in a dark and faithless age: The time is surely coming, says the Lord God, when I will send a famine on the land; not a famine of bread, or a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the Lord. They shall wander from sea to sea, and from north to east; they shall run to and fro, seeking the word of the Lord, but they shall not find it.

Amos prophesied these words in the power of the Spirit, condemning a People who trampled on the needy and exploited the poor of the land. And then, after a long era of absence and hunger, Jesus came to end that famine of the Word. Himself the Word, he came to feed us. He came to speak words he heard from his Father. For Jesus is God’s Word alive in our flesh. And he speaks to us the words of life.

I wonder what he would say to us today, with our facile dismissal of truth and goodness, our frenzied consumption, and our endless stream of glittering images, surface friendships, and wasted words. I think he’d see through us papering over our despair and thinly veiled rage. (Or else letting it out in the open, proudly displaying it for all to view.) He’d notice the futility of our efforts, as violence breaks out again and again.

And he would speak the words of life to us. He would speak them to children with parents in prison, to families living in cars, and to soldiers on food stamps questioning the American dream. He would speak them to grieving widows, sick children, and people wrestling with secret shames. He would speak them to students and teachers and parents, and all who struggle. He would speak them to the survivors of violence, as well as to the oppressed and excluded. He would speak the words of life to us all.

That brings me to T.S. Eliot’s poem “Ash Wednesday,” written in a similar time of crisis. In it, he alludes not only to Ash Wednesday, but to Good Friday and the Cross:

If the lost word is lost, if the spent word is spent

If the unheard, unspoken

Word is unspoken, unheard;

Still is the unspoken word, the Word unheard,

The Word without a word, the Word within

The world and for the world;

And the light shone in darkness and

Against the Word the unstilled world still whirled

About the centre of the silent Word.

O my people, what have I done unto thee.

Where shall the word be found, where will the word

Resound? Not here, there is not enough silence

Not on the sea or on the islands, not

On the mainland, in the desert or the rain land,

For those who walk in darkness

Both in the day time and in the night time

The right time and the right place are not here

No place of grace for those who avoid the face

No time to rejoice for those who walk among noise and deny the voice

Will the veiled sister pray for

Those who walk in darkness, who chose thee and oppose thee,

Those who are torn on the horn between season and season, time and time, between

Hour and hour, word and word, power and power, those who wait

In darkness? Will the veiled sister pray

For children at the gate

Who will not go away and cannot pray:

Pray for those who chose and oppose

O my people, what have I done unto thee.

Will the veiled sister between the slender

Yew trees pray for those who offend her

And are terrified and cannot surrender

And affirm before the world and deny between the rocks

In the last desert before the last blue rocks

The desert in the garden the garden in the desert

Of drouth, spitting from the mouth the withered apple-seed.

O my people.

Jesus, the Word, is spoken to those who choose and those who oppose him. He is spoken especially to those whom others look down on or otherwise exclude. In fact, he died outside the gate, sharing our stigma and shame. He died for all of us, frail human beings—at once saints and sinners, hearers and betrayers of the Word. We have been made one with him in his Body.

And we long for him to speak. We long to see his Holy Face and to hear him speaking to us the words of life…the words that give life—the Word that he is—the Word that he gives, like his Body broken and his Blood poured out for us all.

Lord, to whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life.

The Rev. Canon Bill Carroll serves as Canon for Clergy Transitions and Congregational Life in the Diocese of Oklahoma. He has served as a parish priest in Oklahoma, as a parish priest and college chaplain in Southern Ohio, and as a member of a seminary faculty. In 2005, he earned his Ph.D. in Christian theology from the University of Chicago Divinity School.

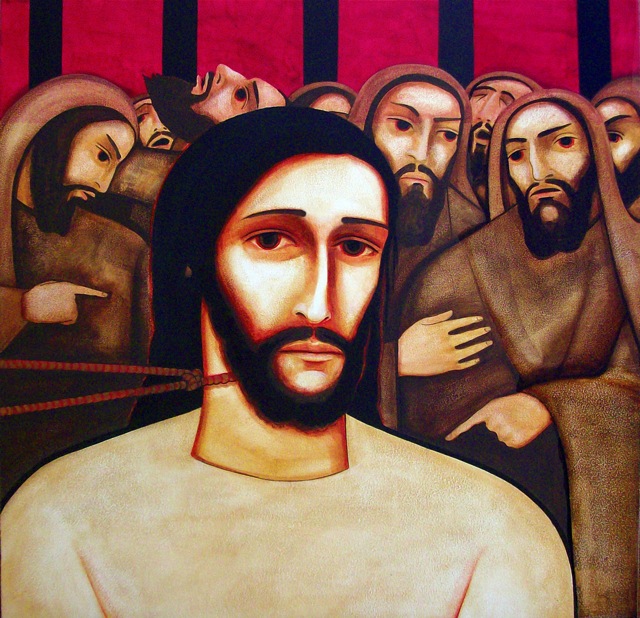

image by Michael O’Brien