THE MAGAZINE

by Tom English

One of the most difficult concepts in Christianity is forgiveness. Perhaps that is because we almost always talk and think about forgiveness in the noun form, keeping us grammatically at arm’s length from the requirement “to forgive,” the verb form. We are required to forgive as we have been forgiven just as we are required to love just as we have been loved. And like love, to forgive and to be forgiven are not feelings, but actions. In fact, love and forgiveness cannot be separated. To love is the will to extend one’s self for the nurture of one’s own and another’s soul. And so it is to forgive. To forgive is an act of love.

The relatives of people slain inside the historic African American church in Charleston, S.C., earlier this week were able to speak directly to the accused gunman Friday at his first court appearance.

“I acknowledge that I am very angry,” said the sister of DePayne Middleton Doctor.

“But one thing that DePayne always enjoined in our family … is she taught me that we are a family that love built. We have no room for hating, so we have to forgive. I pray God on your soul.”

To forgive is a decision, a hard one, not a feeling.

But the legal system grinds on in its pursuit of retribution. The South Carolina Solicitor General announced that she will seek the death penalty for Dylann Roof.

“… We repent of the evil that enslaves us, the evil we have done, and the evil done on our behalf…” In Advent, when my parish uses this alternate confession, I reflected on what it means to “repent of the evil done on our behalf.” I better understand the evil that enslaves us and the evil we (I) have done, but what about the “evil done on our behalf?” Immediately unjust wars and, for me, the death penalty jump to mind, followed by an immediate feeling of powerlessness. What can I do?

My ministry as a deacon at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Eugene has taken me and this congregation out of the pews and into Oregon jails and prisons for almost seventeen years. I could not help but think about what repenting “the evil done on our behalf” means for Christians in the context of a criminal justice system so broken and so brutal as to be a public scandal. When an offender is executed and someone pronounces that “justice was done,” they cannot be speaking of God’s justice, because God’s justice must always include forgiveness and mercy. Just as love and forgiveness cannot be separated, neither can love and justice. John Dominic Crossan, in his book, The Greatest Prayer (HarperOne 2010), describes this relationship best:

“We speak of human beings as composed of flesh and spirit or of body and soul. Combined, they form a human person; separated, we do not get two persons; we get one corpse. Think, then, of justice as the body of love and love the soul of justice. Think, then, of justice as the flesh of love and love as the spirit of justice. Combined, you have both; separated, you have neither. Justice without love or love without justice is a moral corpse. That is why justice without love becomes brutal and love without justice becomes banal.”

My reflection was not on the morality of the death penalty, however as important that issue is, but on the lesser known, relentless brutality of a criminal justice system that sucks the souls out of judges and staff, inmates, victims, families and communities on a daily basis. This also is evil done on my behalf, perhaps more insidious because it gets no headlines, no “news at eleven.” It is routine, normal. God’s justice does require that offenders be held accountable, that victims be restored and communities be safe places for God’s people. And it would be naive not to recognize that some offenders are too dangerous to return to the community. But God’s justice must also be executed in such a way that is restorative and healing for victims, offenders and communities.

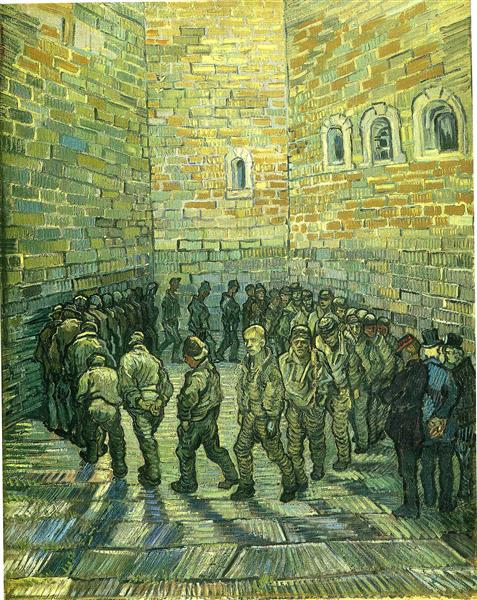

How did our criminal justice become so broken? Who is to blame? The answer for me is I am, we all are responsible. Christianity itself also bears significant responsibility for the use of incarceration. Seen as reform from torture and capital punishment, prisons were built throughout the United States in the mid-1800s with the intention not only of incarcerating but also improving prisoners through a mixture of work, discipline and personal reflection. But when the reform movement died, prisons became out of sight and out of mind for most Americans. We were glad they were there because they made us feel safe. But we paid scant attention to what went on inside the walls. Underfunded, understaffed and increasingly over-crowded, our prisons became warehouses or worse where inmates are punished. As members of the Church and of a polity where citizens are sovereign, we are called not only to be compassionate to those who violate our laws but to seek a justice which truly protects our communities, restores victims and holds offenders accountable while not blunting their chance at reconciliation with brutality.

The church has the tools to first acknowledge responsibility and call for reforms necessary to create a truly restorative criminal justice system. As a Church we meet, we teach and we preach. We have sent our people into prisons and jails to work with both inmates and staff. We have helped offenders return safely and successfully to our communities. We have provided care and comfort to victims. But is not enough. Repentance offers us the opportunity to right the wrong and to forgive ourselves for waiting too long to act. We are created free in the image of a freedom-loving God. “To take that freedom away from people is to exercise an awesome responsibility because it strikes at the heart of human dignity and identity. So the first thing the biblical record invites us to recognize is the exquisite pain imposed by imprisonment; why it hurts so much, and thus invites us to use great caution in resorting to it.”

There are things we can and, as a Christian must do, to repent the evil done on our behalf. Not to act is to be complicit.

- As people of God we can add our voices, and that of the Episcopal Church, to the growing recognition of a broken and brutal criminal justice system. We can educate ourselves and, as citizens, demand humane and effective reform.

- We can visit the prisoners. If your state is like Oregon, roughly 40% of prisoners receive scant or no visitation at all. Recent research demonstrates that even casual visitation make a positive difference in prisoner mental health and success in returning to community. In Hebrews13:3 we are told, “Remember those who are in prison, as though you were in prison with them; those who are being tortured, as though you yourselves were being tortured.” In Matthew 25 Jesus identifies himself with those in prison, so that those who care for prisoners actually encounter the anonymous presence of Christ. “I was in prison and you visited me.”

- Finally, we must take action to meet those returning to the community with generous hospitality and the resources they need to make a successful re-entry into our communities.

If we focus prayerfully and lovingly on these three elements, we are actively repenting.

The Rev. Deacon Thomas R. English is Co-Chair of the Episcopal Diocese of Oregon Prison Ministry Commission.