THE MAGAZINE

by Robert W. Prichard

Although it might not always be clear from stewardship sermons, Christian attitudes about Church finance have changed frequently over the centuries in response to changes in the cultures and economies of the nations in which Christians lived. In the case of the Episcopal Church in United States, there have been multiple overlapping patterns of church support.

During the colonial era, patterns of support depended on the colony in which a church was located. In those states in which the Church of England came to be established (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) the legislature designated land for church buildings and glebes (land that could be farmed by clergy or rented to produce income) and gave the church vestry the right to levy a tax (called a tithe but actually a flat tax on everyone who had wealth above a certain level). With the right to tax came also the responsibility for social welfare; churches supported orphans and widows, and other impoverished persons, and assisted with the care of the sick. (The move to give these duties to the vestries began when Parliaments in Elizabethan England realized that no one had assumed the public welfare responsibilities once exercised by the non-longer existing monastic orders.) The combination of glebe lands and tithes was at times sufficient to support the church, but it generally was not big enough for major capital projects, such as the construction of church buildings. That was often financed by soliciting subscriptions from church members and staging fundraising events such as lotteries.

This system in the colonies with Anglican establishment did not produce uniform returns or lead to a uniform clergy salary structure. Eighteenth-century clergy salaries in Maryland, where the governor selected the clergy, were, for example, higher than those in other colonies. Church finance also differed within individual colonies. In Virginia, for example, clergy were paid in pounds of tobacco; where soil was rich—in the Tidewater area—the tobacco brought a higher price, and thus more financial assets for the parish, than it did in upland areas.

The major source of income of those colonies that lacked Anglican establishment was the missionary societies: the Society from the Promoting of Christian Knowledge (SPCK), which bought books; the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), which paid clergy salaries; and Dr. Bray’s Associates, which funded missionary efforts to African Americans. This support was particularly important in rural parts of New England, where the more affluent people attended the established Congregational Church, and the Anglican Church ministered to people of modest income. There may have been, however, a handful of self-supporting congregations in major cities in New England and the Middle colonies.

Tax and missionary society support halted at the American Revolution. The English missionary societies cut off funds as a result of provisions in their charters that limited support to British territory. Colonial legislatures ended the taxing ability of the vestries and—in the case of Virginia—began to confiscate glebe lands and other church property. This sudden change left clergy with very little in the way of financial resources and led many congregations to close. Clergy filled the economic gap in a variety of ways, including serving as military chaplains and doubling as school masters.

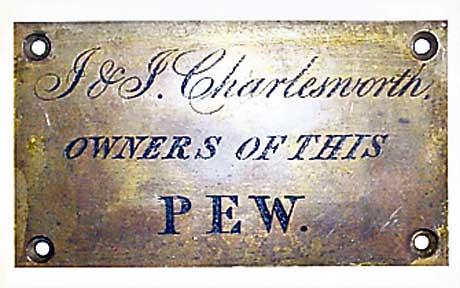

By the early part of the 19th century, the church had found a two-part system to replace lost income. They began to rent pews (or in some cases to levy an annual fee for pews that were already owned by parishioners), much as professional sports teams or opera houses do today. Funds received were used for the ongoing support of the parish budget. Special fundraising campaigns were still conducted for church building and special offerings were also collected for charitable projects: Sunday school, missions, etc.

This system was relatively effective and was used widely by multiple denominations. By the middle of the 19th century, however, some began to notice that the system had social implications. Those too poor to rent pews were either limited to balconies and “stranger pews” in the back of the church, or stayed away from the church altogether. William Augustus Muhlenberg’s Church of the Holy Communion in New York City eliminated pew rents in 1846, becoming one of the first mainline Protestant Churches to do so. It was a bold move, made possible in part by the support of Muhlenberg’s sister, who was a wealthy widow. In 1877, two years before Muhlenberg’s death, supporters of the idea created the Free and Open Church Association of the Protestant Episcopal Church. The General Convention kept statistics about the success of the association’s campaign, recording figures about the number of free and rented seats in the Episcopal Church up until the second decade of the 20th century.

By 1910, only 20% of the seats in the Episcopal Church were rented; the remaining seats were free. It was not immediately clear what system was to replace pew rents, however. Women’s groups were increasingly successful in fundraising at that point, financing the construction of buildings, overseas mission, and charitable projects though such mechanisms as parish aid societies and the United Thank Offering. They owed their success in part, however, to their focus on special projects rather than to more hum-drum continuing parish costs, and were unlikely to replace funds lost by the elimination of pew rents. Endowments were another possible resource. By 1910 the pooled parish and diocesan endowment funds managed by the Trustees of the Estate and Property of the Diocesan Convention of New York had reached $840,815.11, a significant increase over the $61,587.16 in the fund in 1886. Returns were, however, relatively modest with only five parishes in the diocese receiving more than $1,000 a year from the fund. Other forms of support were needed.

The solution would be the every member canvass, a reformulation of the tithe as a percentage of cash salary (rather than a flat tax), and a technique for linking giving to support the parish to external charitable support. Two major national Episcopal fundraising campaigns—one to create the Church Pension Fund (1915–17) and the other a “Nation-wide Campaign” (1919) to create endowment to support outreach projects—demonstrated the value of concerted fundraising campaigns. Individual Episcopalians had been extolling the merits of a tithe of one’s cash salary since the publication a pamphlet by the Rev. C. P. Jennings of the Diocese of Central New York titled The Christian Treasury, or the Church’s Sources of Income (1878). It would not be until the 1920s, however, that the majority of Americans lived in towns or cities and earned cash salaries that made the tithing argument reasonable. A new invention—the duplex envelope system—allowed parishioners to use a single envelope to link the previously separate giving to the parish budgets and outreach. This funding approach would be re-emphasized following the Depression and World War II, both of which depressed church attendance and giving.

While the General Conventions of the late 20th and early 21st centuries have continued to affirm the importance of tithing a tenth of one’s income (General Convention Resolutions 1982-A116, 1988-A164, 1994-A120, 2009-D055), there have been shifts in the pattern of giving put in place in the 1920s. It has been common, for example, to suggest that the tithe is not only a standard of giving for individuals but also a target for parish giving to the diocese and diocesan giving to the National Church. There has been a renewed emphasis on the creation of endowments to support parishes and programs (The Consortium of Endowed Parishes, 1985). Some churches have followed a 19th century English pattern and begun to charge fees for use of facilities. Under Dean Gary Hall (2012-15), for example, the National Cathedral began to impose admission fees on those who visit the building outside of occasions of worship. It is common for some parishes in urban areas to charge significant fees for non-members in search of a venue for weddings. New financial instruments such as debit and credit cards, automatic bank withdrawals, and online donations have created new ways in which people can make contributions. It is would appear that the Episcopal Church is in a period of transition similar to that of a century ago—a period in which old funding approaches are being tested and new ones tried, but one in which a single consistent new approach to church finance has not yet emerged.

The Rev. Robert W. Prichard is the Arthur Lee Kinsolving Professor of Christianity in America and Instructor in Liturgy at Virginia Theological Seminary.