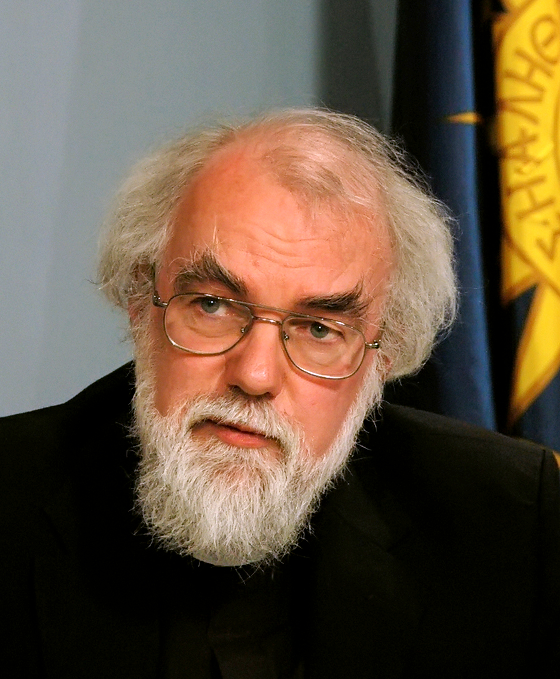

Former Archbishop of Canterbury and current Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, Rowan Williams reflects on the controversy stirred up by the Lord’s Prayer advert banned by a cinema conglomerate in the UK in last night’s London Evening Standard.

You know Christmas is coming when the papers begin to fill up with stories of well-meaning and cloth-headed persons trying to avoid the terrible threat represented by mentioning the Christian origins of Christmas (the clue is in the name…). It is so obviously offensive to be reminded that singing about peace and goodwill started two millennia ago, for a very particular reason, on a hillside in Bethlehem.

The delicate and sensitive public — impervious to industrial levels of cinematic violence and internet trolling — has to be protected from this appalling truth.

Williams’ defense of the ad rests on two poles, which are not entirely aligned with one another. One the one hand, he argues that as a member of the public, he is assaulted frequently and unwillingly with competing philosophies of life, and that disallowing this one is unfair.

Now, when I go to the cinema (not very often, I admit), I have to sit through an assortment of adverts actively and aggressively promoting a set of values and myths that I find mostly incomprehensible or alien.

They are myths about the happiness that comes from acquiring various consumer goods, values illustrated in sophisticated (and eye-wateringly expensive) bits of film that nurse some of our most childish fantasies about power and success.

As a cinemagoer, I’m being carefully targeted for conversion to a philosophy of life. If I don’t like it, that’s my problem. After all, this philosophy of life is completely self-evident to the film-makers, and assumed to be acceptable and attractive to every sane citizen. So advertising our Christian history is not intruding dangerous propaganda into a neutral and benign space. It is competing with existing propaganda, existing philosophies and ideologies.

He does not, however, believe that the “Christian history” promoted by this advert is equal and comparable to those of consumerism and film fantasy – nor, as a senior cleric, should he.

Yes, it encodes a philosophy of life — one that a lot of us would still find understandable and might even wish we could live by a bit more consistently. It is a philosophy shaped by the conviction that we are most human when least obsessed with defending and promoting our self-interest and when recognising our shared human needs.

The problem is, says Williams, that the general public has decided that all religion is dangerous stuff.

Religion has fostered cruelty, obsession with power, inhuman repression, exploitation, dishonesty and misery. We tend to forget that much the same is true of politics, capitalism, socialism, science, alcohol, sex and football.

And

Every vicar is really a mad jihadist in mufti.

If he is defending the advert on the grounds of competing philosophies, then the concept of free speech and fairness may be his argument. But when Dr Williams promotes the virtues of the Lord’s Prayer and its history against a background of “peace and goodwill, to coin a phrase,” his choice of tone towards the general public, “cloth-headed persons,” and popular culture might be found to work against him.

Which is not to say that Dr Williams is wrong about the public perception of religion, at least according to the comments sections of various online news outlets. One comment to his own article responds:

here is no such thing as sane religion.

like mental health problems there is a wide spectrum, from those with harmless problems who will make a harmless nuisance by e.g. talking to themselves in public, through to those who can not restrain themselves from murdering everyone in sight… but they are all still problems.

unlike mental health problems, which are not the fault of the sufferer, it requires a continued and conscious effort to persist in having religious beliefs in the face of morality and intelligent thinking, especially in the modern world.

So what are the ways in which we can promote an image of Christian religion as a force for “peace and goodwill” in the world?Advertising prayer? Arguing for advertising prayer? Or something else? Read the article here, then have your say below.