THE MAGAZINE

by Maria Evans

“Now such remarks have I wished to advance in defense of the flesh, from a general view of the condition of our human nature. Let us now consider its special relation to Christianity, and see how vast a privilege before God has been conferred on this poor and worthless substance. It would suffice to say, indeed, that there is not a soul that can at all procure salvation, except it believe while it is in the flesh, so true is it that the flesh is the very condition on which salvation hinges. And since the soul is, in consequence of its salvation, chosen to the service of God, it is the flesh which actually renders it capable of such service.”

–Tertullian, Chapter 8, “On the Resurrection of the Flesh”

It is an unmistakable physical anatomical fact that we are made of meat–and lots of it. Muscles, ligaments, tendons, vessels, nerves, connective tissue, and bone all make up the physical aspects of our humanity. Meat can be cut, torn, and crushed. It can become necrotic or gangrenous. It can also pulse with every drop of the warmth of our blood, and animate our every move on this planet in our lifetime.

Before Tertullian succumbed to the heresy of Montanism, though, he challenged Marcion’s heretical idea that Jesus was somehow this divine illusion of meat–a human BocaBurger, if you will–to spare Christ from suffering on the cross. Tertullian insisted that Christ’s divinity was still wrapped up in meat, just like ours, that can bleed when it’s severed, hurt when it’s crushed, and caused him to suffer just as we suffer when it happens to us. As a result, as divine as grace and salvation are, they are still wrapped in meat–our meat–because of the incarnation of Christ. Christ didn’t just appear as a disinterested disembodied illusion of us, he was us.

Recent developments in the meeting of the Anglican primates illustrate there are those among us that still feel squeamish about the enfleshment of God’s love as expressed by monogamous committed relationships among pairs of LGBT Christians. Any recent flip through the U.S. political news reveals there are those among us who don’t want to enflesh refugees, Muslims, hungry people, homeless people, or the mentally ill. When I think of my own failings in my dealings with people, the times that make me cringe at my own brokenness are the times that I’ve managed somehow to emotionally de-flesh someone and make them a concept, or something less than a human being with meat and sinews on their bones. The illusion, of course, was that I could somehow reasonably and rationally de-personalize my feelings about something or somebody that hurt me. But in the end, I only de-personalized myself.

Perhaps the one true piece of evidence of our brokenness as human beings is our propensity to create a straw version of whatever it is about humanity that makes us feel uncomfortable or threatened, and toss matches at it without a second thought. Perhaps the greatest temptation any of us faces that has the risk of catapulting us into spiritual peril is to be tempted by the notion that we can somehow act on the tensions that plague our human existence without getting bloody ourselves. To pretend that our own brokenness doesn’t come into play is denial at best, idolatry at worst. Coming to terms with our own meatiness and God’s willingness to be meat among us is hard.

Yet, at the same time, it is precisely in the Eucharist where we are reminded again and again of Tertullian’s axiom, within the paradox of “broken” and “whole.” A loaf of bread can be completely intact, but, according to our theology, it isn’t truly whole until Christ is present in it. Yet the priest doesn’t use that whole piece of bread as a shrine to be guarded and protected–it is broken and distributed to broken people in the hopes they become more whole and go out into the world as agents of God’s restoration–God’s quest to make the world more whole. Part of that restoration is to resist the temptation to deny the fleshiness of those who wish to obliterate or shun our own flesh. Perhaps the toughest thing in the world is to see the people we disagree with the most as enfleshed beings, too.

The larger truth, of course, is that love, generosity, kindness and compassion stem from the messiness of life rather than from a disembodied notion of perfection. Christ became flesh to enter into a new relationship with our flesh. We know the genuine article because we’ve experienced the pain and emptiness of what isn’t.

When is a time that speaking or acting from your own brokenness enabled you to be the person most capable of rendering service to God?

Maria Evans, a surgical pathologist from Kirksville, MO, is a grateful member of Trinity Episcopal Church and a postulant to the priesthood in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri. You can also share her journey on her blog, Chapologist.

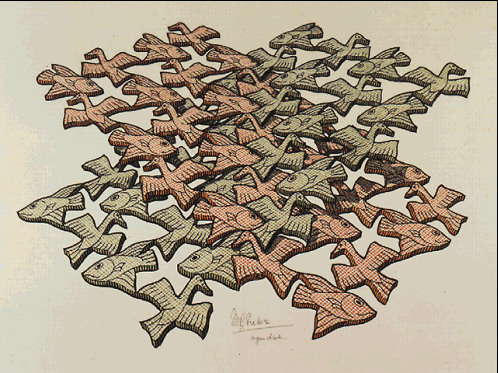

image: Twon Intersecting Planes Colour by M. C. Escher