The New York Times reports on a research paper investigating the political opinions of religious leaders in the USA, and finds that

America’s pastors – the men and women a majority of Americans look to for help in finding meaning and purpose in their lives – are even more politically divided than the rest of us, according to a new data set representing the largest compilation of American religious leaders ever assembled.

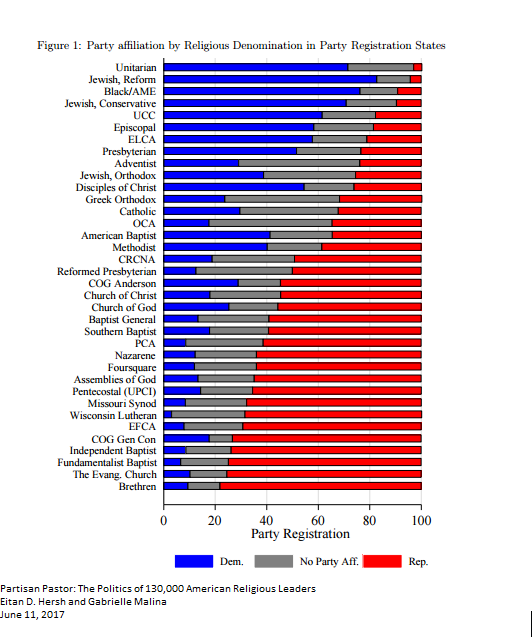

The researchers, Eitan D. Hershand Gabrielle Malina, described their interest in the Introduction to “Partisan Pastor: The Politics of 130,000 American Religious Leaders.”

With detailed data on pastors within all of the major denominations, we expect to find that a denomination is much more informative of a pastor’s political affiliation than a congregant’s. The causal process that may have led denomination to bear a weaker relationship to politics in the mass public is unlikely to apply to pastors. After all, pastors are religious elites who represent specific denominations and their associated theological worldviews. In weekly sermons, pastors translate the connection between theological teachings and real world social and political issues for their congregants. From such a position of spiritual and moral leadership, pastors can shape the political agendas of congregants, as well as advocate specific issue positions that likely hold greater weight than positions taken by other political or social elites.

The New York Times summary of their results supports the conclusion that pastors are more politically cohesive within denominations than their congregants.

Consider Methodists and Episcopalians, two Christian denominations whose congregants have relatively similar political compositions, with 43 percent and 55 percent identifying as Democrats, respectively, according to the Cooperative Congressional Election Survey. But their pastors’ politics are quite different. While Methodist pastors are just as split as their congregants, Episcopalian pastors are strongly Democratic, roughly equivalent to Hawaii or Washington, D.C., in terms of partisanship.

This difference extends to the political views of members of the two churches. Episcopalians were much more likely than Methodists to express support for issues like gay marriage, immigration and abortion rights. Across denominations, the researchers found that the political affiliation of a congregation’s leader was a stronger predictor of the congregation’s policy views than the political affiliation of the congregation as a whole.

In other words, the personal political opinions of the pastor have significant weight when it comes to the direction and involvement of the congregation as a body politic.

Read the New York Times report here, and the original research paper here.