by George Clifford

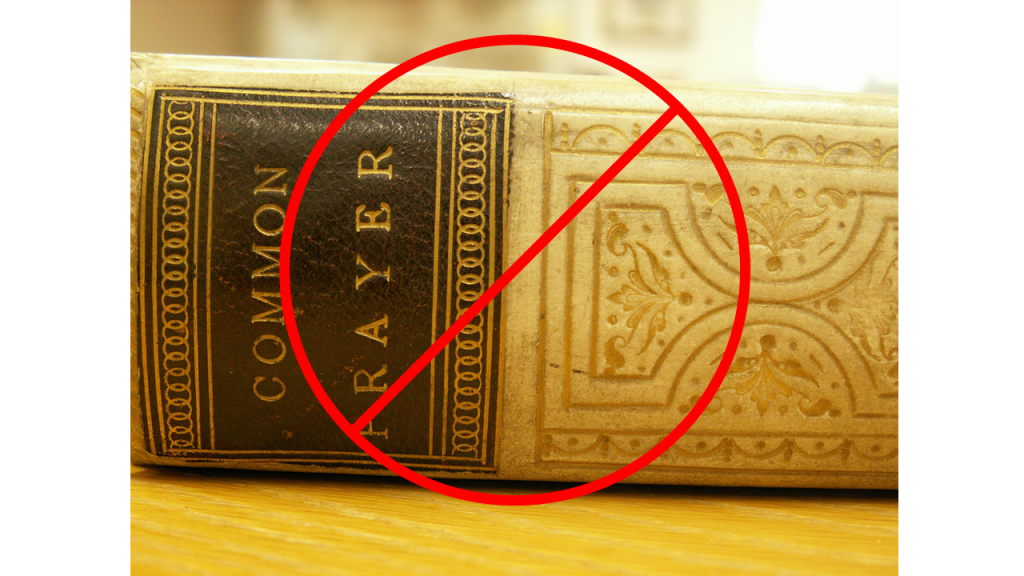

In my last contribution to the Episcopal Café, I proposed that The Episcopal Church (TEC) publish its next revision of the Book of Common Prayer exclusively in a digital format. That proposal triggered a flurry of comments, mostly negative. Those responses are worth answering even though they failed to address many of the issues I raised in support of TEC utilizing an exclusively electronic (digital) Book of Common Prayer.

Revising the Book of Common Prayer will require at least ten years from today. If next year’s General Convention (GC) appoints a task force or tasks an existing body to draft a revision, the 2021 GC might forward that draft to dioceses for comment, asking the body that drafted the revision to carefully consider those comments; the 2024 GC could then debate the revised draft, probably amending sections and perhaps authorizing trial use; if the trial enjoyed popular acceptance, the 2027 GC might adopt the revision as TEC’s new prayer book. The actual timeline would conceivably (probably?) take longer, especially if some groups find some of the proposed revisions particularly problematic.

By 2027, our world will be far more digitally dependent than it is in 2017. Comfort with electronic media will be even more widespread. Some elementary, middle, and high schools already issue each student a personal computer or tablet, increasingly relying upon digital instead of printed materials. A growing percentage of college textbooks are available only in a digital format. Commercial sales of e-books continue to grow rapidly.

Consequently, for many people juggling a bulletin, prayer book, and one or more hymnals while trying to worship will feel increasingly awkward, distracting, and unhelpfully anachronistic. A forward-looking TEC will choose to adopt contextually appropriate technology rather than clinging to outdated media. As one response to my proposal noted, printing the first Book of Common Prayer represented utilizing the best technology then available. Since that time, branches of the Anglican Communion have published various editions of the Book of Common Prayer adapted to their context and in their language(s). Moving to an exclusively digital version of the Book of Common Prayer is simply the logical progression of this living tradition.

Furthermore, the proposal to publish any revision in an exclusively digital format is actually less radical than it might appear. TEC and others (some unauthorized) already make the Book of Common Prayer, other liturgical resources, and much of our hymnody available electronically. Illustratively, growing numbers of people, ordained and lay, say the daily office utilizing digital resources that incorporate the relevant Book of Common Prayer materials and prayers, scripture readings, and sometimes music and/or historical information about the saint(s) or event commemorated that day.

Incorporating hymns and service music into the revised electronic Book of Common Prayer may likely, as another respondent noted, raise copyright issues. That is not a reason to reject electronic publishing. Instead, it constitutes an issue that those who draft the revision and TEC’s lawyers will have to address. A printed Book of Common Prayer that incorporates hymns and service music would be both physically unwieldly and too large to fit in most pew racks. Only an electronic version offers the convenience of having all of our liturgical resources in a single, readily accessible source.

A digital resource will allow congregations and dioceses to make unauthorized changes, a problem that more than one respondent to my original proposal highlighted. These respondents ignored my observation that this already happens. Like them, I value being part of a Church that is defined by common prayer rather than common belief. However, ostrich like behavior that tries to ignore the unfortunate practice of local, unauthorized changes to the Book of Common Prayer’s liturgies and rubrics is not constructive. Not printing a revised Book of Common Prayer will neither accelerate or decelerate the use of unauthorized changes to the liturgy. This is a separate issue, one that deserves our attention, but not a reason to object to publishing a revised, comprehensive Book of Common Prayer in an exclusively digital format.

Currently, TEC has a number of alternative liturgies (e.g., for the eucharist) that congregations may use with their diocesan bishop’s permission. These liturgies are not in the Book of Common Prayer. Thus, congregations utilizing these liturgies must either print a service leaflet that contains the full liturgy or leave attendees in the dark about the timing and wording of participatory responses. These liturgies represent a de facto step away from total reliance upon a printed prayer book and a step toward use of a digital resource. The same issues arise when using the Book of Occasional Service’s seasonal and other liturgical resources.

Advantageously, relying upon a comprehensive, digital version of TEC liturgical resources will allow timely, no cost updates to language and content, e.g., replacing the outdated, exclusionary masculine terms in the rubrics with gender neutral ones and including both newly adopted materials as well as items authorized for trial use. As the multiple revisions to the Book of Common Prayer in this and other Anglican provinces attest, the Church’s worship is framed in continually evolving language and liturgy.

Finally, none of the respondents to my original piece adequately addressed the substantial financial costs to congregations and individuals who would need or desire to purchase printed revisions of the Book of Common Prayer and other TEC liturgical resources. These costs would greatly strain the financial resources of many of our small congregations. And TEC consists primarily of small congregations. One respondent did raise the important issue of environmental harm attributable to an increased number of congregations printing a leaflet for each service containing the full liturgy. However, that cumulative negative effect will very probably be significantly less than the combined adverse environmental effect attributable to printing both tens of thousands of copies of a revised Book of Common Prayer (TEC has over 5000 congregations) and the weekly leaflets containing the full liturgy that many congregations presently print.

I appreciate some people deriving personal comfort in holding a printed book. However, the Church is not about me or any other individual. The Church exists to minister to the world, particularly those hurting or spiritually empty persons who seek a different or new form spirituality. Over half of all Episcopalians began their Christian journey in another denomination. Concurrently, the fastest growing religious demographic in the US is the number of people who self-identify as having no religious preference, many of whom lack any religious background. Meanwhile, our culture is relentlessly switching to digital.

Becoming a people who truly welcomes both those moving from another denomination and those with no previous religious identity requires TEC to make its worship resources and materials as user friendly as reasonably possible. One vital component of this welcome is to provide the entire liturgy, words and music, in an easily accessible format, e.g., leaflets printed with the full liturgy, loaning attendees a handheld electronic device that displays the liturgy, projecting the liturgy onto one or more large screens, or a mix of these options. A digital Book of Common Prayer that includes our hymnals and other liturgical materials best supports all of these options, best utilizes TEC resources, and is most contextually appropriate for TEC as it lives into the twenty-first century.

George Clifford, a priest in the Diocese of Hawai’i, served as a Navy chaplain for twenty-four years, has taught ethics and the philosophy of religion, and now blogs at Ethical Musings.