There has been a whirlwind of reactions to the grand jury investigation in Pennsylvania which uncovered thousands of abuse cases over many decades and a pattern of denial and coverup that continued to imperil vulnerable children. Several people offered their thoughts to the Café; below we offer some of those in hopes that we in the Episcopal Church might redouble our efforts to make church a safe and welcoming place.

We start with Tom Buechele, a retired (but still serving) Episcopal priest who was formerly a Roman Catholic priest in Iowa and his reflections on the culture he knew then and how it came to where we are now.

Once again the Roman Catholic Church is rocked by sexual abuse charges by priests against children. This time it’s 6 Diocese’s in the State of Pennsylvania.

For me it’s like round 10 of a heavyweight championship fight. Round 1 was when I was a Roman Catholic Priest in the Diocese of Davenport, IA. (1968-1989). Time and again some of us clergy were witness to some really strange behavior by our fellow clergy.

One day as I was coming in the Chancery Office (Bishop’s and Diocesan headquarters) in Davenport, the then 2nd in authority to the Bishop was rushing out of his office.I asked, “what’s the hurry?” He responded like I should already know, “I have to go down to Ottumwa, IA to bail Fr.———- out of jail.” Oh, really., I thought. What’s that all about?

Later, I learned that the priest had been arrested for molesting a child. He admitted to Diocesan authorities as early as 2002, that he had abused at least 12 boys. He was infamous in the sexual abuse charges that were brought against the Diocese in 2007. The New York Times reported on December 4, 2007 The Roman Catholic Diocese of Davenport, Iowa, reached a $37 million settlement to compensate victims of sexual abuse by clergy members and let the diocese emerge from bankruptcy. At that time the plaintiffs were 156.

Some of us priests of the Diocese were quite concerned early on. There were “let’s get nude” gatherings of priests and seminarians with lots of alcohol. I was so grateful I was never invited. There would have been immense pressure to attend as priests of authoritative positions were involved in the gatherings.

Many conversations at dinner and social gatherings among us clergy brought up the names of many priests who were suspected child abusers. Gradually it became clear to some of us that child abuse was frequent in the Diocese. We also came to learn that there is and was “no cure.” Still the prevailing mind set of the authorities was that if only they could get treatment. If only we assign them to places where there are not many children.

Some of us brought it up at Priest Senate meetings, only to see the subject ignored. I was told by a priest friend, who was on the national Priestly Life and Ministry Committee, that clergy abuse of children had come before the national Bishop’s conference a number of times, only to be buried by the then Cardinal of Philadelphia…guess where? PA.

Bishops who supported coming clean and admitting the scourge were later not promoted to offices of higher rank in the USCCB. They were ignored and passed over for promotion.

Sexuality and sexual identity were basically ignored in our clergy formation. The integration of appropriate sexual response in one’s life was never addressed.

We were dismally unaware and uneducated. I clearly had my own sexual misgivings and guilt from “sins”. Many acted out in adult homo-sexual relationships, many more in adult female relationships. I sought counseling outside the confines of Church structures and finally left the active ministry after 22 years.

I have since learned that good priest friends of mine had been abused as children by their parish priests or that they had brothers and sisters who had been abused. Their pleas and complaints went unacknowledged. And then still other priest friends were accused of sexual abuse only later to be found innocent.

Truthfully, I mourn for the good guy priests. Those who have stayed in spite of abuse, either by intimation or in reality. I mourn for those who “blew the whistle” that nobody heard. I mourn for those who remained faithful to their vows and maintained a balance through years of faithful service.

As in the case of the #METOO it was never about an exciting and pleasurable sexual act, it was about the distortion and abuse of authority and power.

As William Falk, a Catholic High School graduate and Editor-in-Chief of The Week, wrote “If the Church is to reclaim its lost moral authority, it will have to tear down its secretive, all-male hierarchy. If the Church is to be saved, it will let priests marry, and it will welcome women into the priesthood and Vatican. The alternative is increasing irrelevance.”

Next, we hear from Nathan LeRud, Dean of Trinity Cathedral in Portland, OR who also shared these thoughts in the opinion pages of the Oregonian newspaper. This was posted here at the Cafe earlier this week as well.

Sexual abuse in church tears families apart, destroys lives and relationships, and can severely damage a trusting relationship with God. Christians around the world have been deeply and rightfully disturbed by news in recent days concerning the Pennsylvania grand jury investigation into the abuse perpetrated by hundreds of Roman Catholic priests. Stories like this are not new: Many religious leaders have betrayed the trust of many faithful people, and not just in Roman Catholic churches. The times in which we live make this an important moment to reckon honestly and compassionately with the realities of gender, power and sex abuse in our houses of worship.

The Episcopal Church’s record in regard to sex abuse is far from spotless. Our priests and lay leaders have been guilty of horrible crimes, and our institution has tended to protect the powerful at the expense of their victims. Although my denomination has different structures of authority in place that have helped to mitigate against the scale of abuse other denominations have seen, this is not a moment for any faith community to claim moral high ground. When one part of the body suffers, all suffer. Many faithful people, and not just Roman Catholics, will have to answer for the sins committed by some clergy. I feel this in a visceral way when I walk down the street wearing a white clergy collar. In that moment, it doesn’t matter how my denomination’s practices and policies may differ from another’s: I represent a faith tradition that has damaged thousands of lives. The pain and trauma experienced by some in our midst is the responsibility of us all.

Therefore all faith communities — not just Roman Catholic communities — must work for change. Becoming communities of radical hospitality requires that we become communities of trust, where the integrity of pastoral relationships is preserved and protected. At Trinity, we are looking closely at our screening and monitoring policies around sex abuse. We have been scrupulous over the past decades in screening and monitoring those who work with children, and now we are expanding our policies to all volunteers who represent the Cathedral, whether they’re teaching church school, singing in the choir or serving the homeless. Abuse doesn’t just happen to children. Congregations must learn how to look out for each other and treat one another with respect and dignity, regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, ability or creed. Not because our liability insurance requires us to, but because this is the kind of people Jesus calls us to be.

Many Christians are offering prayers for victims of abuse. This is important. But prayer without action is prayer incomplete. I encourage other faith leaders to join me in taking necessary steps to ensure that systems of safety and accountability protect the most vulnerable in our midst. It may be some of the most important work we do, when we do it in the name of Jesus.

And lastly, Eric Bonetti asks could something like the scale of abuse seen in occur in the Episcopal Church and highlights some shortcomings in our own policies and polity. Eric is a lay person and regular contributor to the Café.

The recent release of the Pennsylvania grand jury report, which details allegations of sexual misconduct between Catholic priests and more than 1,000 children and vulnerable adults, has created a firestorm of controversy in the media, and rightly so. But before members of other denominations, including The Episcopal Church, breathe a sigh of relief, it makes sense to ask the question, “Could it happen here?”

The answer, I suspect, is that it could, for even with the recent changes enacted at General Convention, protections within The Episcopal Church do not go nearly as far as do those in many Roman Catholic dioceses. Thus, with fewer protections — or roadblocks, if you will — against bad behavior, it is entirely possible that The Episcopal Church could experience a similar scandal.

In considering these possibilities, let’s start by looking at Catholic Church policy. This includes the Model Code of Pastoral Conduct, which has been adopted by many Catholic dioceses, including Pittsburgh. (References in this article are to the version adopted by the Pittsburgh Diocese, found in PDF here.) In reviewing this policy, several things are immediately clear:

Catholic policy is more specific than most Episcopal policies. For instance, the former specifically addresses inappropriate photography, conflicts of interest, use of alcohol while serving as a volunteer, responding to emergencies, access to locker rooms and other high-risk locations, various forms of non-sexual harassment and more.

Catholic policy is broader than most Episcopal policies and includes a wide variety of pastoral boundaries. For example, the Catholic policy covers gossip, intimidation, respect, disclosure, physical intimacy with friends and family members of those with whom clergy have a pastoral or counseling relationship, conduct by lay volunteers, and many other aspects that touch on healthy church dynamics. In short, Catholic policy isn’t just about preventing sexual misconduct; it’s about maintaining healthy boundaries at all levels of church.

Of course, there’s a larger issue, and that is that many Episcopal dioceses don’t even have such written policies. Instead, dioceses typically rely on the often amorphous guidance afforded by church canons, as interpreted by the bishop, canon to the ordinary, and possibly the chancellor, as well as local vestries and wardens. That, of course, presupposes that these individuals have both the time and the knowledge needed to be effective in these roles—suppositions that, in today’s era of resource constraints at all levels, may prove to be at variance with reality.

Where the Catholic Church really excels, however, is in the advantages afforded by its relatively monolithic structure. Thus, while dioceses retain considerable latitude in implementation and approach, there are key aspects of Catholic policy that are non-negotiable. These are enforced by an audit, conducted by an independent outside audit firm, per written policy established by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, which includes site visits, review of misconduct prevention training, a detailed assessment of church responses to allegations of misconduct, reviews of costs associated with misconduct prevention training, and more. The annual report is voluminous, with the 2017 version comprising 74 pages, and is made publicly available in PDF here. It’s well-done, and a good read for those who may wish to professionalize misconduct prevention within The Episcopal Church.

There’s another, higher, policy level at which the Catholic church excels in its efforts to protect against misconduct, and that is within its Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People. That document establishes a church-wide framework for efforts to prevent misconduct. Among other things, it:

Establishes a cultural baseline for a pastoral response to allegations of misconduct, including ongoing efforts at healing at reconciliation, predicated on Pope Benedict’s pronouncement, “It is your God-given responsibility as pastors to bind up the wounds caused by every breach of trust, to foster healing, to promote reconciliation and to reach out with loving concern to those so seriously ”

Establishes the requirement for clear, publicly disseminated standards of clergy conduct in all dioceses and eparchies.

Forbids confidentiality agreements as part of settlements of allegations of wrongdoing, unless requested by the complainant.

Clearly states the willingness of the Catholic church to share research and other resources in the effort to eliminate the scourge of sexual abuse of minors.

Creates a structure, organization, and policies to assess, on an ongoing basis, the efficacy of training, reporting, and compliance efforts.

This contrasts sharply with the results of the recent Episcopal General Convention, in which the House of Bishops repeatedly removed provisions from proposed legislation that would have incentivized dioceses to implement specific provisions to protect against sexual misconduct, and established reporting on such diocesan efforts. That begs the question: If the episcopacy indeed is serious about eliminating sexual abuse and misconduct, why not be publicly accountable?

Consider these actions in light of the findings of the report commissioned to study the failures of the church in the wake of the Heather Cook debacle:

[I]n almost every case that we examined, the ecclesial structure and polity of our church proved to contribute negatively to the situation. Clericalism, a misunderstanding of hierarchy, the canonical autonomy of parishes and dioceses, and a polity that hinders the enforcement of expectations all contributed to inactivity by responsible persons and bodies (such as bishops, chancellors, vestries, Standing Committees, search committees and consultants, Commissions on Ministry, and seminaries)….An often underdeveloped theology of forgiveness also contributed to the abusers being given multiple opportunities to repeat their behaviors without consequences.

Moreover, the report notes that efforts at the national level to address alcohol abuse by clergy date back to 1979. A review of the resolution passed in 1979 by General Convention reveals that most diocese still have not followed through on its requests that the dioceses establish written policies for the treatment and care of those struggling with addiction.

Meanwhile, anecdotal evidence suggests that misconduct prevention training efforts remain similarly hit or miss in the Episcopal church. Why do I say anecdotal? Because there is no central point of collection for data on these efforts, even within most dioceses. Indeed, few if any dioceses audit compliance with sexual misconduct prevention training, and it is not unusual to encounter parishes in every diocese in which people are entirely unaware of such requirements. Nor is there any real mechanism to deal with local clergy who choose not to comply, and it’s a safe bet that clergy who do engage in misconduct probably are not the first in line when it comes to implementing policies and guidelines to protect against such actions.

Nor do most dioceses have any formal mechanism to care for victims of misconduct outside the limited provisions of the Title IV disciplinary canons. Even there, training and familiarity with the requirements of Title IV is uneven, with many bishops, canons to the ordinary, and other officials unsure of their role in the process. Thus, those who bring forward a claim often must hope for a sympathetic bishop, intake officer, or local clergy; if these aren’t present, there is little likelihood of a positive outcome. Indeed, it’s worth noting that Catholic policy discourages use of clergy as intake officers, as victims of abuse may find it difficult to share their experiences with a member of the clergy.

Of course, not everything is sunshine and roses in the Catholic church. The Pennsylvania grand jury report is a damning piece of documentation that will result in lasting issues for the church, including loss of membership and diminished trust. Moreover, the annual compliance report notes pointedly that many prior suggestions made by the audit firm have not been implemented, while further commenting on the tendency within the church to become complacent—proof that churches, for all their differences in polity and doctrine, often are remarkably consistent in their approach to such matters.

Meanwhile, some positive signs are afoot in The Episcopal Church. The recent shift in national policy to recognize that abuse comprises much more than sexual misconduct is a good sign, as is the recognition that abuse affects women and men as well as children. And, at least on paper, members of the House of Bishops have pledged to work towards a safer church for all persons.

Where does this leave The Episcopal Church? From this author’s vantage point, the answer is that The Episcopal Church is late to the game. While it may not face the challenges caused by the requirement of celibacy, the accomplishment of GC79 seem, at best, a recognition of the need to move forward and improve the church’s efforts to prevent and respond to abuses of power. Meanwhile, there exists the very real threat that the church could experience its own major crisis as people more fully explore issues of power and abuse within the church.

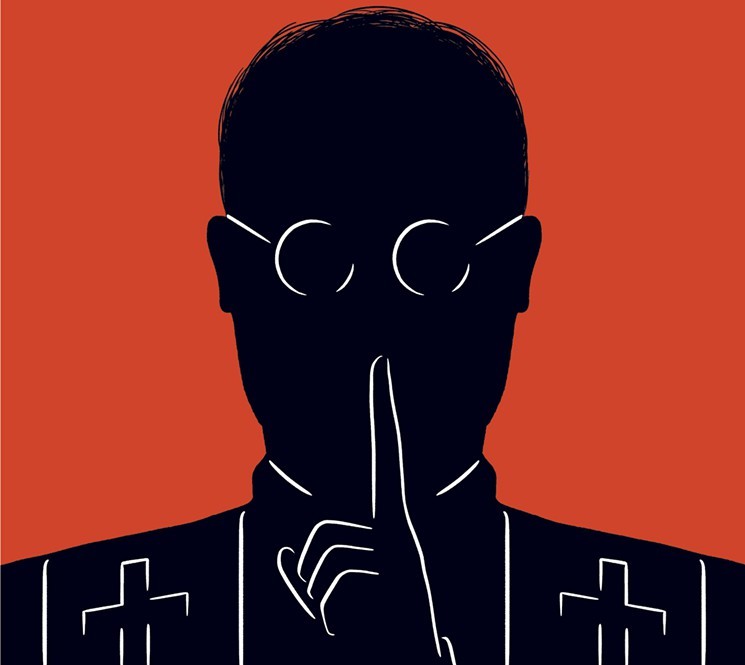

image by Matt Chase, Dallas Observer