THE MAGAZINE

Several years ago, I read a piece in a major daily publication about the reemergence of excommunication among mainline Protestant denominations. “Thank God I’m part of a denomination that doesn’t engage in that craziness,” I thought, perhaps a bit smugly.

Today, I have learned through personal experience just how wrong I was.

I know what you’re thinking. Right about now you’re saying, “But the only form of excommunication we have, per the Book of Common Prayer, is repulsion from communion. Either the author doesn’t get it, or he did something really awful and was asked not to take communion.” Sadly, neither is true.

My problems began when, as a vestry member, I discovered numerous questionable financial practices in my parish. The details aren’t important, but it’s fair to say that any prudent person would have cause for concern. Similar issues abounded in the area of human resources, where staff routinely complained about harassment from other staff members. And the discovery of a non-parishioner, late at night, shredding papers in the parish offices shortly before a major staffing change, was disconcerting, to say the least.

I tried hard to be fair. My rector was someone I liked tremendously, and I said to myself repeatedly, “He just doesn’t understand the issues, and he’s got a lot on his plate.” And knowing that seminary provides little training in the administrative skills needed to run a parish, I felt certain that the issue was primarily that the rector, from his vantage point, just didn’t see the ugliness that went on behind the scenes.

Certainly, I knew that change doesn’t come easily. And it’s axiomatic that change agents can face strenuous pushback.

That said, as I continued to lobby to fix these issues, I was startled to discover that the most vociferous opponent to change was none other than the rector. “That’s odd, I thought. Surely he can see the damage that these issues are causing the parish. And I know he cares.”

Things became worse in the following months. We had several situations in which my rector publicly excoriated me, including in front of non-parishioners. I spoke one-on-one with my rector, asking that he share any criticisms or concerns about me one-on-one, versus in public fora, and that seemingly fixed things for a while.

But the problems continued, and more and more I saw the can being kicked down the road, and my concerns ignored or dismissed. Or they’d be blocked and countered; I’d complain about a staffing issue, and the rector would say, “But that person is gone.” To which I’d reply, “But that’s not who I am talking about, and I don’t know why you are bringing up someone else.”

Finally, in frustration, and increasingly concerned about the possibility of personal liability, I resigned from the vestry. The announcement surprised no one, given the very public slights that the rector had sent my way over the previous year.

The good news, I thought, is that my resignation would allow me to share my concerns with the diocese, without placing myself in a situation of possibly divided loyalties. Surely, I thought, the diocese would want to fix things.

Wrong again. My complaints were largely brushed off and I was told that workplace harassment was not a violation of the canons. Nor were verbally or emotionally abusive behavior by clergy or employees under their control. Same for major discrepancies in the parish financials and serious breakdowns in internal financial controls. Increasingly, it seemed like rape and murder were the only two things that would cause the diocese to act against clergy, and I wasn’t so sure even about those.

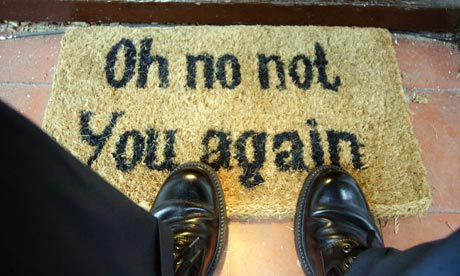

Shortly afterwards, I got an email from the rector. It was a sneaky bit of priestly double-speak, for it attempted to make it sound like I had already left the parish and transferred elsewhere, which was not the case. But the real message was clear: “Neither you nor your family are welcome in this parish.” In addition, the email announced that the rector, on his own initiative, had removed me from various positions within the parish, including an elected one. This was done very publicly, resulted in speculation in certain circles that I or someone in my family had somehow done something truly evil.

Shortly afterwards, my parish email account suddenly went dead. We stopped receiving parish mailings. A prayer request, sent by a family member on my behalf after a serious accident, vanished, never to appear in the bulletin. Parish staff and volunteers both confirmed that they had been instructed to exclude me and my family from parish life.

More of the same followed. My family’s name disappeared from the parish directory, despite the fact that we continue to pledge and attend services, the latter at least occasionally. Three memorial donations my family made disappeared into space; the funds were received and not returned, despite not being used per the terms of the solicitation. (A few days ago, faced with imminent litigation, the parish agreed to return the funds.). And several matters that were specifically confidential were allegedly shared by the rector with parish staff and others.

It’s fair to say that the situation has truly caused me great suffering. For the first time in my life, I have suffered from depression and panic attacks. I’ve also developed an anxiety-related case of irritable bowel syndrome, culminating in a disastrous and humiliating experience at family celebration last summer. But I am taking medication to address these issues, and getting psychological care, both of which are helping.

In recent months, a new wrinkle has emerged, which is character assassination, apparently from clergy in the parish. One allegedly questioned my integrity to a third party, while another apparently said, through a vestry member, that I am “unbalanced.” The result is that my family and I are shunned by a great many people that we used to consider friends.

Where are other parish leaders in all this? The answer is mixed. My observation is that unhealthy family systems rarely see themselves as such. And charismatic clergy who abuse their powers can lead even educated, sophisticated laity down the wrong path with surprising ease, particularly when, as here, they have built up years of personal loyalty within the parish.

Where is the diocese in all this? So far, sitting on its hands. It would seem a simple matter for the bishop diocesan to tell the clergy in question to knock it off, but this has not happened. And working towards healing and reconciliation would seem to be in everyone’s best interest, but the diocese has made no move to do so. And anytime the matter lurches into the public eye, there are those who speculate that somehow I am behind it. Certainly, I continue to resist being bullied, but it must also be recognized that the matter has taken on an ugly life all its own. Meanwhile, one diocesan official asked, “Why would you even want to be part of that parish?” But that’s not the point—the point is clergy misconduct, and the question is insulting.

Where is Jesus in all this? It’s a question I wish the diocese would ask. Jesus, it seems, would support healing and reconciliation. And he would be all too familiar – and none too happy — with clergy who use their positions to oppress others.

It’s ironic, too. When the Title IV disciplinary canons were revised, the concern was all about the disciplinary process being used to bully clergy. Yet laity appears to have little recourse against abusive clergy. Unless it involves sex or outright theft, you are on your own in many dioceses, and there is nothing in the canons that explicitly prevents de facto excommunication, as I have described here.

Would I again be willing to address questionable management, financial and human resource issues in my parish? I like to think so, but these days, I am not so sure. Given everything I’ve been through, it would be far easier to turn a blind eye.

The flip side is it’s disheartening that one the hallmarks of Episcopal polity, which is democratic self-rule, seems not to apply in this case. Traditionally, the paradigm is that the parish can’t get rid of the priest without the bishop’s permission, and the priest can’t get rid of laity, absent criminal activity or other serious wrongdoing. It is under this ordered scheme of governance that I gave sacrificially of my time, talent, and treasure, yet my rector purports to be able to unilaterally separate me from my investment. Had I known that to be possible, I would have been much more judicious in my giving. And if it comes to it, I am going to insist that my pledges be returned, as I gave within the framework of our canons, but these canons are no longer being applied in my parish. Instead, it seems to me that the parish is an autocracy. A pleasant one for those who go along and don’t make waves, but an autocracy nonetheless.

What does the future hold? I don’t know. But there have been some positive outcomes. I have made a surprising number of new friends. Others, that I considered friends, have fallen by the wayside, and that’s probably for the best. And I have seen several individuals, my rector included, for what they really are. That in itself is encouraging, for I suspect that few ever have that opportunity.

Meanwhile, we’re a resurrection people, and I’m reminded that what initially looks like an empty tomb can, in fact, be a sign of great joy. Perhaps we’ll even see an effort in future general conventions to prevent abuses of these sorts.

Your prayers for me, my family, and those I love, as well as my rector and parish, and my diocese, would be be greatly appreciated. I hope to be able to write more at some point, perhaps with more positive news.