by Gerry Lynch

Around the turn of the century, a theory emerged that the internet would render geography irrelevant; that we would all become digital nomads, telecommuting across continents with the ease with which we might pop down to the 7/11 for milk.

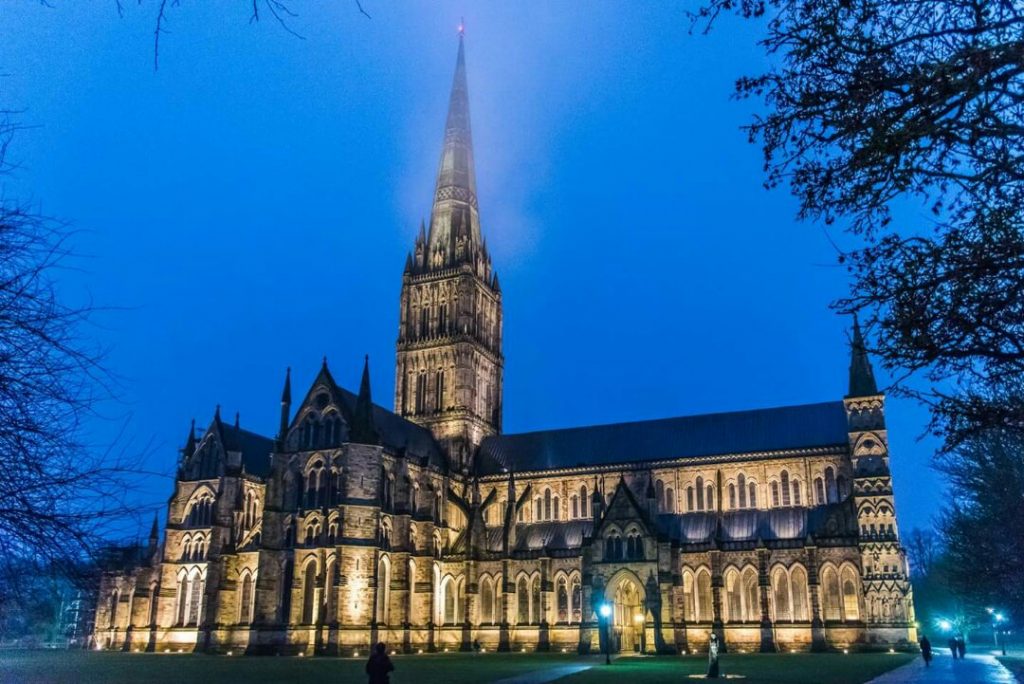

To a limited extent, that has in fact happened; I wrote this piece partially in each of two very different locations. Half was written in the extraordinary surrounds of Salisbury Cathedral Close, Europe’s largest; its 400 acres are traditional, genteel and ancient, surrounding a building where prayer and praise has been offered to Almighty God every day for nearly eight centuries.

The other half was written in the very different surrounds of the Maboneng Cultural Precinct in Johannesburg, where a new neighborhood of studios, workshops and apartments is rising in one of the most challenging parts of the City Centre, where armed battles between police and criminal gangs were commonplace until recently. The energy, creativity, and dynamism are life-giving, as is the joy of a racially integrated quarter in a city with a tragic history of dehumanizing people because of the color of their skin.

Both Maboneng and Salisbury Cathedral Close are, in very different ways, what the early Celtic saints might have called ‘thin places’, places where it is easy to detect the divine breaking into the mundane world. One is a place where the peace, gracefulness and timelessness of God surround people; the other is one where God’s energy, creativity and inclusiveness are the air one breathes on every street.

For, despite the over-optimistic claims of the turn of the century digital prophets, place still matters profoundly. There are negative as well as positive consequences of that. Far from our workplaces becoming geographically detached from where we live, over the past 20 years, jobs have concentrated in the biggest metropolises. In those cities, living costs have spiraled. “Making it” professionally for young adults increasingly means being able to sustain either exorbitant rents or excessive commutes on low wages – this is, increasingly, a privilege reserved to those who have parents willing and able to provide a generous subsidy.

Good jobs lie increasingly behind prohibitive economic walls of high housing costs, not just London to Los Angeles, but also from Johannesburg to Jakarta. Becoming a digital nomad generally involves spending time in a high cost metropolis first. This is part of what is directing the rage in ‘left behind’ communities in America’s flyover country, the left behind post-industrial town of Britain and France, but also in places like India and the Philippines, where a crude, angry, nationalism plays well in poverty stricken provinces that seem set to be permanently excluded from prosperity.

So, making more places viable and pleasant places to live is one of the key questions facing the 21st Century world, despite the internet. Any Christian case for a just social order must take note of the importance of place and the damage wreaked on people in places which are ignored and despised. The places in which we live and work can include or exclude, liberate or repress, inspire or depress. They matter tremendously to us.

Places also mattered to Christ, profoundly so. The child for all peoples and all times was born in Bethlehem, raised in Nazareth (can anything good come from Nazareth?!?!?!), died and rose from the dead in Jerusalem. He was a man of and from definite places, each of which had particular reputations and social resonances.

Two places stand out in the Gospel record for their importance to Christ: the desert and the Temple.

Deserts, like the rest of our world’s retreating wildernesses, are vital to sustaining our planet’s ecosystem. For Christians, they have additional importance: as the last remains of earthly creation before The Fall, however we understand that concept, they connect us with our Maker in a direct and profound way, too deep for words, healing us when the cares and demands of the world threaten to overwhelm. Christ is like us in every way except sin, and that includes that he found His earthly ministry at times spiritually and pastorally exhausting. It was the wilderness that refreshed and healed his soul.

In contrast, the Temple was a human-made place in a bustling city environment. Places of worship are in important respects sacramental. Like the Eucharistic elements, they involve the working of the natural bounty of God by human hands and human minds, with the product thereof surrounded and saturated by prayer.

The psalms that have been sung in Salisbury Cathedral over many centuries are the same as those sung in The Temple when Christ walked its precincts. Prayer is soaked into the Cathedral’s stones. It has been a place where many weary souls have found rest and refreshment. The daily round of prayer has been offered – and this is truly extraordinary – more than a quarter of a million times. Walking through one of the gates into the Close, one senses time expanding to become what it truly is, a stream that connects us to the infinite it just as it grounds us in the moment. Physically, it is a beautiful building in a beautiful setting, for sure, whether on a balmy summer evening as the magical light of sunset in these high latitudes grows slowly richer and redder; or on a winter day when the mist rolls across the grass and enshrouds the spire.

The sense of awe one feels here, however, is more than merely a function of beauty; the presence of God is palpable: “ineffably sublime”, as the words of the hymn might put it. There is something genuinely out of this world there that is difficult to describe and impossible to quantify. That, in itself, is a refreshment in a world where we are categorized and numbered and monetized to make it easier to sell us things we don’t need to an extent that degrades our humanity.

George Herbert was one person who sensed that ineffable presence in this majestic Cathedral. Rector at Bemerton, then a separate village but now a district of Salisbury where his church of St Andrew remains open daily for prayer, Herbert would walk the mile or so across the water meadows to attend Evensong, sometimes carrying an instrument to assist with the music making. It was the round of prayer in Salisbury and Bemerton that called to Herbert to reject privilege, professional advancement and potential power to become a simple country parson.

Beyond the Cathedral, Sarum College is another powerhouse of prayer in the Close. It has been training priests and offering Christian hospitality for 150 years, welcoming students and visitors from across the world. Its prayer life has been greatly enriched by the arrival in 2010 of a Benedictine community in the house next door.

Sarum College offers lodgings and meals to students, pilgrims, conference delegates and ordinary tourists. Far from the world of corporate hotel chains and corporate academia, the welcome visitors receive is unforced, gentle and warm, rather than slick and saccharine.

It is a privilege to give people the opportunity to refresh their spirits in this profound, prayer-soaked, environment.

Visitors of all faiths and none are welcomed. One Muslim groups holds its annual conference at the College every year, citing the peaceful atmosphere – and the food! That is an important symbol in a world threatened by fundamentalisms. Many of the tourists who stay are of no particular faith, but find themselves touched by awe in spending a night or two in Salisbury Cathedral Close.

But for Anglicans and Episcopalians, this is a particularly special place. American Episcopalians, especially, tend to take delight in finding that a world that had existed in their imaginations is real. Of course, we have our challenges and disputes in the Close: this is a real, living and working, community, not a plastic theme park. It is, however, a real place of refreshment.

Many of our visitors leave after a week or a month with their commitment to their existing ministry renewed or else with definite plans for a change; others find they have the space to develop ideas for a book, a building project, or a new social ministry.

More than that, time in a “thin place” like this can help people see how deeply God is present where they are. For God is just as present in the strip malls, the housing projects and the cookie-cutter suburbs as He is in places where His presence is easily palpable and, yes, ineffably sublime.

A little bit of the sublime does us all good from time to time!

Gerry Lynch is the Communications Director for the Diocese of Salisbury in the Church of England. His photo, used above is Salisbury Cathedral at Night

Staying in Salisbury’s Cathedral Close

To arrange a slice of the sublime in Salisbury, England, contact Sarum College by email info@sarum.ac.uk or telephone (44) 1722 424800. Rates and availability can be found on our Stay at Sarum page, though our hospitality staff will offer special price packages for longer stays with meals and library access. Sarum College staff can also give advice about sources of grants for study breaks, email development@sarum.ac.uk for further information.