THE MAGAZINE

by The Rev. Harold Clinehens, Jr.

I purchased Naomi Klein’s book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate back in January. According to “The New York Times”, “The Guardian”, “Christian Century”, Bill McKibben, National Public Radio, and God knows who else, Klein’s tome is the new required reading for all matters relevant to climate change.

And yet, it sat on the corner of my desk for over two months. I saw it every day and every day, thought, “I really need to start reading that…” yet, I did not. There was a part of me that really didn’t want to know what was in it… perhaps a metaphor for the denial and dilly-dallying many of us practice around this scary subject.

But as I was packing for my annual Lenten retreat, I threw it in the car and then spent most of the retreat reading it. I hope… no, I pray that you’ll read Ms. Klein’s book yourself, but in the meantime, here’s a summary of the central thesis: Because of our decades of mass denial and dilly-dallying, we now are left with a stark choice: Allow climate disruption to change everything about our world, or change pretty much everything about our economy to avoid that fate. Now.

For decades, climate scientists have been sounding the alarm: Reduce emissions down to a level that (hopefully) will keep the planet from warming no more than 2 degrees Celsius, or face disastrous consequences. And because of our endless delays, The International Energy Agency now warns that if we do not get our emissions under control by 2017, our fossil fuel economy will “lock in” extremely dangerous warming. As Fatih Birol, the IEA’s chief economist, bluntly put it, “The door to reach 2 degrees (Celsius) is about to close. In 2017 it will be closed forever.” Yikes!

If that statement doesn’t catch our attention, I don’t know what would. Admittedly, a lot of people might say, “What’s the point? We’ve blown it.” But not Naomi Klein. When asked, “Is it possible for us to reach this goal?” Her response is “absolutely.” But then she rejoins,“ Is it possible without making a bunch of structural changes on many different levels? Not a chance.”

Years ago, in the midst of feeling the familiar anxiety around preparing for the annual parish fund raising effort, someone cut through all the usual machinations, and stated the best definition of stewardship I’ve ever heard: Stewardship is all we do with all we have, all the time. If the stewardship of our dollars is important, how much more so, our planet? Both involve sacrifice, yet many of us go blithely on our way, unwilling to be inconvenienced even a little bit, when it comes to our behavior vis a vis the resources we use.

On our way to the aforementioned retreat, my spouse and I observe the same thing we do every time we’re on the highway. We consistently drive 70 miles per hour (too fast for optimum fuel consumption), yet people consistently overtake us as if we’re sitting still. I’m old enough to remember that there was a time when the national speed limit was 55 mph.

The National Maximum Speed Law (NMSL) in the United States was a provision of the 1974 Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act that prohibited speed limits higher than 55 miles per hour (90 km/h). It was drafted in response to oil price spikes and supply disruptions during the 1973 oil crisis.

While the law was extremely unpopular, widely disregarded by motorists, and ultimately repealed by Congress in 1995, it did reduce fuel consumption (and therefore emissions). The safety benefits of the law were also disputed; despite the fact that in the first year the law took effect there was a decrease of 4000 in the number of automobile fatalities. Predictably, after the law was repealed, traffic fatalities increased by 15%.

Go ahead and laugh, but I wish we’d return to a national maximum speed law. If such a speed limit were enforced, not only would emissions be reduced, but states that now constantly complain about not having enough revenue would have a lot more of it in their coffers. And yes, I understand that compared to coal-fired power plants and multinational manufacturing, reducing our highway driving speed would be but a drop in the bucket, but is that a reason not to do it?

It’s not unlike fasting. A good reason to fast is, it’s OK to be a little hungry, not to mention the slight sense of solidarity we might feel with the two billion plus people in the world who are always hungry. Likewise, slowing down on the highway inconveniences us just a little. Can we inconvenience ourselves for the sake of the planet? For the sake of each other? As a statement of solidarity that we’re all in this together, and each trying to do our small parts? In the words of Jon Kabat-Zinn,

“The little things? The little moments? They aren’t little.”

A few years ago, when crossing the border from Washington State into Canada, I noticed a sign on the Canadian side admonishing motorists not to idle their engines while waiting. It was a little thing, but the message was clear: Canadians are thinking about reducing fuel consumption and emissions; and encouraging consciousness and behavioral change (notwithstanding the oil lobby’s barbaric commitment to extracting Canadian tar sands). How many times have we seen someone step out of a car with the engine running and the AC going, lock the car, and disappear for five—ten—fifteen minutes? We have to change the way we think and the way we behave. 2017 is just around the corner.

President Jimmy Carter was known for encouraging energy conservation long before it was “cool.” In July of 1979, he addressed the nation about the fact that “too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption… He urged Americans “For your good and for your nation’s security to take no unnecessary trips, to use carpools or public transportation whenever you can, to park your car one extra day per week, to obey the speed limit, and to set your thermostats to save fuel. Every act of conservation like this is more than just common sense—I tell you it is an act of patriotism.”

The address was initially well received but came to be derided as the “malaise” speech and is still invoked as proof that any politician who asks voters to sacrifice to solve an environmental crisis is on a suicide mission. The speech also has been criticized because Carter proposed no structural modifications that could change corporate behavior.

Certainly, one set of rules does need to apply to players big and small, and many structural changes need to be implemented as soon as possible. In This Changes Everything, Naomi Klein makes many outstanding suggestions for both structural change and how each of us can become more involved in our communities.

But that doesn’t let you and me off the hook regarding our personal, daily, hourly behavior. It occurs to me that President Carter’s words are more prescient than ever.

Stewardship is all we do with all we have, all the time. Can we inconvenience ourselves a little? Because “the little things… the little moments… they aren’t little.”

The Rev. Harold Clinehens is a retired Episcopal priest, who’s served parishes in the Dioceses of Northern California, San Joaquin, Arizona, Los Angeles, Northwest Texas, and Arkansas. He and his wife, Beverley, reside in far Northern California under the shadow of Mount Shasta.

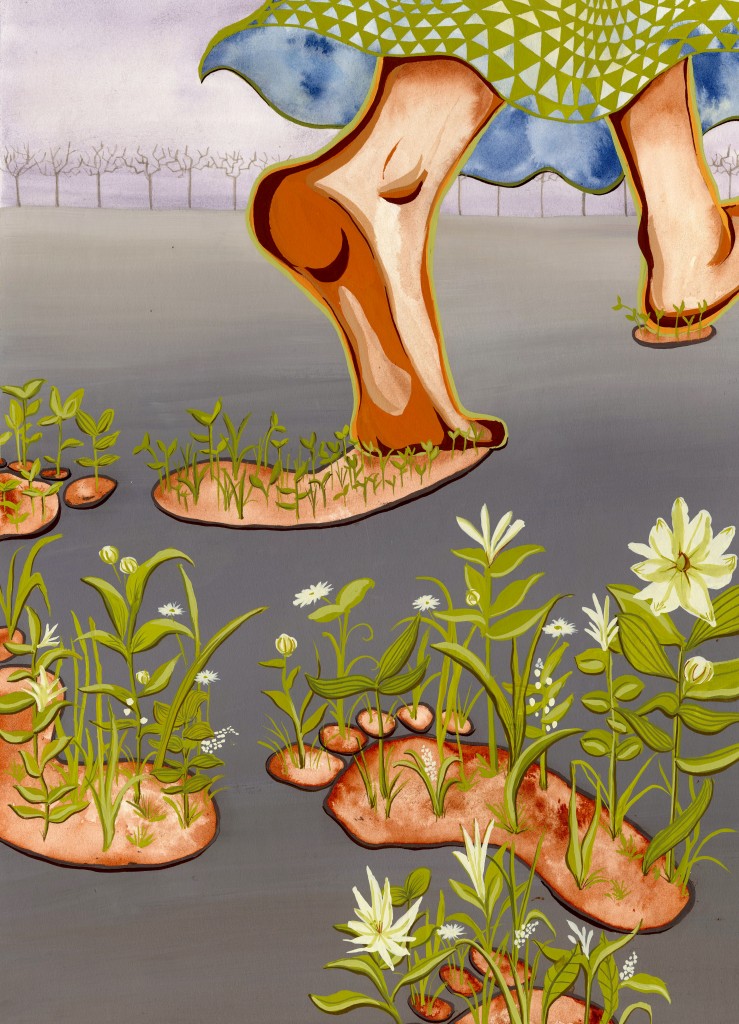

illustration by Caitlin Ng