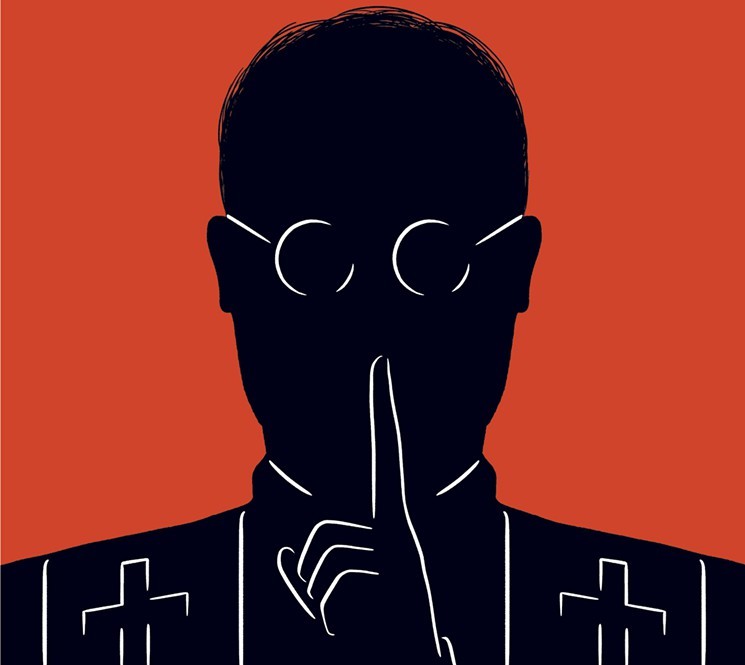

For nearly two decades, since at least the Boston Globe investigation in 2002, sexual misconduct and abuse by clergy-persons has been a prominent cultural issue. Stories of abusive behaviors have been shared across the religious spectrum; in the Southern Baptist Church, The Roman Catholic Church, and in the Episcopal Church as well.

By and large, repeated investigations around the world of various churches have found that church hierarchies prioritize protecting their own reputations over either caring for victims or seeing that perpetrators face justice. It should not be too difficult to imagine that the revelations of cover-ups and duplicity on the part of church authorities is a significant contributing factor to falling trust in religious institutions.

Yet despite the continuing uncovering of pervasive abuse and resultant cover-ups, church authorities seem to repeatedly be shown not grasping the scale or seriousness of the trauma. Given this tendency towards dismissive-ness; responses around the world has been, by and large, ineffective and half-hearted.

Recently, Pope Francis promulgated new canon laws meant to address the problem. Outlined in an apostolic Letter called Vos Estis Lex Mundi, the Roman church, for the first time, defined a process for reporting allegations, supporting victims, and protecting whistle-blowers with actionable means of accountability. Notably, though, the accountability on offer is only within the church and the new law does not mandate reports to civil authorities, though bishops in the US do have guidance that encourages reporting and working with civil authorities.

Accountability that stops short of extra-institutional justice seems unlikely to satisfy a skeptical public that the church is not just another institution focused on self-preservation above mission. And even though most of the public scrutiny (at least here in the US) has been focused on the Roman church; ALL churches are affected as the vast majority of those outside the church are unlikely to appreciate the nuances of denominational identity.

One potential barrier to a more open church with greater accountability is the expectation of confidentiality in confession. Most churches have held this confidentiality inviolate in the belief that without it, potential penitents would not seek reconciliation with God and the church, though that belief has never been scrutinized in any methodical manner of study. The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayers says, concerning reconciliation (p446); “The secrecy of confession is morally absolute for the confessor, and must under no circumstances be broken.”

Of particular note in the Episcopal church’s rite for Reconciliation of a Penitent is the absence of manifested repentance in the rite. The penitent’s promise of an amended life is as close it gets. Though the priest may offer “counsel, direction, and comfort” after the penitent offers confession, there is no explicit expectation of restoration or justice for any victims before absolution is pronounced.

A slim majority of states have included clergy in their mandated reporting laws. However, most of those also recognize a clergy-penitent privilege that exempts knowledge learned through a process of reconciliation from the mandatory reporting requirements.The absolute seal of the confessional is, however, being challenged. Proposals to force mandated reporting, even in confession, have been advanced in Australia and California.

The Church of England has its own history of childhood sexual abuse as shown in the recent UK government Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. Several years ago, the CoE set up a working group to examine whether the seal of confession should cover cases such as child sexual abuse. In a recent statement, the group summed up the current status as;

Having listened to the person’s confession of sin before God, the priest will help

them to know God’s forgiveness afresh. That includes a formal prayer for ‘absolution’

(i.e. being released from guilt for sin), and also guidance about how to walk the path

of repentance. That may mean a readiness where appropriate to face the legal

proceedings by which justice is upheld within our society. The current Guidelines for

the Professional Conduct of the Clergy state that ‘If, in the context of such a

confession, the penitent discloses that he or she has committed a serious crime,

such as the abuse of children or vulnerable adults, the priest must require the

penitent to report his or her conduct to the police or other statutory authority. If the

penitent refuses to do so the priest should withhold absolution’

In an understated way, the working group report acknowledged that the absoluteness of the seal was under attack, suggesting that this may be an area where the church’s traditional perspective is up for reconsideration.

At present, the ‘seal of the confessional’ is upheld in the Church of England’s

ecclesiastical law. The Working Party did not reach a consensus as to whether this

should change. The diversity of view within the Working Party would be reflected

more widely in the Church of England. Some Anglicans feel very strongly that the

ministry of confession is an integral part of the church’s life of the church, and that its

proper practice is inseparable from the unqualified observance of the seal. Some

observe from their experiences that the Seal of the Confessional can offer comfort to

survivors of abuse who, trusting in the absolute discretion it promises, may confide in

a priest for the first time and by so doing find that they are able to unburden

themselves and begin the process of healing. Others feel very strongly that the

church cannot continue with any aspect of its practice that stops information being

passed on which could prevent future abuse or enable past abusers to be brought to

justice.

Continued uncovering of the history of abuse and cover-up found in Christian churches will only make demands for accountability grow louder. The long-privileged status of the Christian church in the US is decaying and our exemptions from common expectations, like reporting knowledge of sexual abusers, along with it. Convincing a skeptical public of our commitment to prevention and accountability of predatory practices is an evangelical imperative.