THE MAGAZINE

By Kelly Wilson

Four weeks had passed since Palm Sunday, and the splintering leaves were still everywhere.

My wife and son had not been able to go to church with me, so I decided to bring home a handful of the long, stringy fronds, still wet from the usher’s bucket. Now the leaves lay drying on every table, shelf, and floor of the apartment. Yet we couldn’t throw them away. They were “sacramentals.”

The veneration of “blessed” objects is still relatively new to me. I grew up in a simple, Midwestern evangelical church, with grape juice for communion and a plain wooden cross on the wall. Back then, the veneration of a leaf would have been seen as pure idolatry.

Now, as an adult, I belong to an Episcopal church in a large urban cathedral. I work part time on the cathedral staff, so I get a “backstage” view of items being blessed, kissed meticulously folded, and otherwise cherished—even communion wafers that fall on the floor are dutifully consumed by the priests.

While I’m still skeptical that crackers literally become flesh, I do believe the sacred rituals and objects help align my mind—otherwise entangled in workaday concerns like balancing the checkbook—to an attitude of awe in the divine presence.

But I still don’t know all the rules of what to do with the “sacramentals” after we’re done with them.

I asked a few friends what they do with their leaves after Palm Sunday.

One friend, a lifelong Catholic, described hanging the palms over a crucifix on the wall, then returning them to church the next year to be burned for Ash Wednesday. I knew churches burned last year’s palms for ashes, but never realized parishioners brought them back after keeping them all year.

Many people fold the fronds into little crosses, then tuck them behind the wall clock or hang them from the rear view mirror. I had one of these crosses last year—my wife learned to fold them as a kid—but I don’t know where it went. There are probably centuries’ worth of relics similarly lost in homes all over the world, secretly radiating blessings from behind the dresser or the back of the drawer.

One friend didn’t realize her husband had been putting palms under the bed, year after year, until they moved and found a great pile of dead leaves under the mattress.

In the end, I went to where any good pilgrim would turn: Google.

Most religious websites agreed that I should hold onto the palms as keepsakes or bring them back next year. One suggested giving them as gifts, but that would just be passing my responsibility onto the next guy.)

I found my answer in the “Catholic Q & A” section of the Eternal Word Television Network website–a credentialed authority, to be sure: “Blessed palms may be burned and returned to the earth or simply buried.”

As long as I could find a lightly trod area to dig—not the easiest task in Manhattan—I could simply return them to the earth.

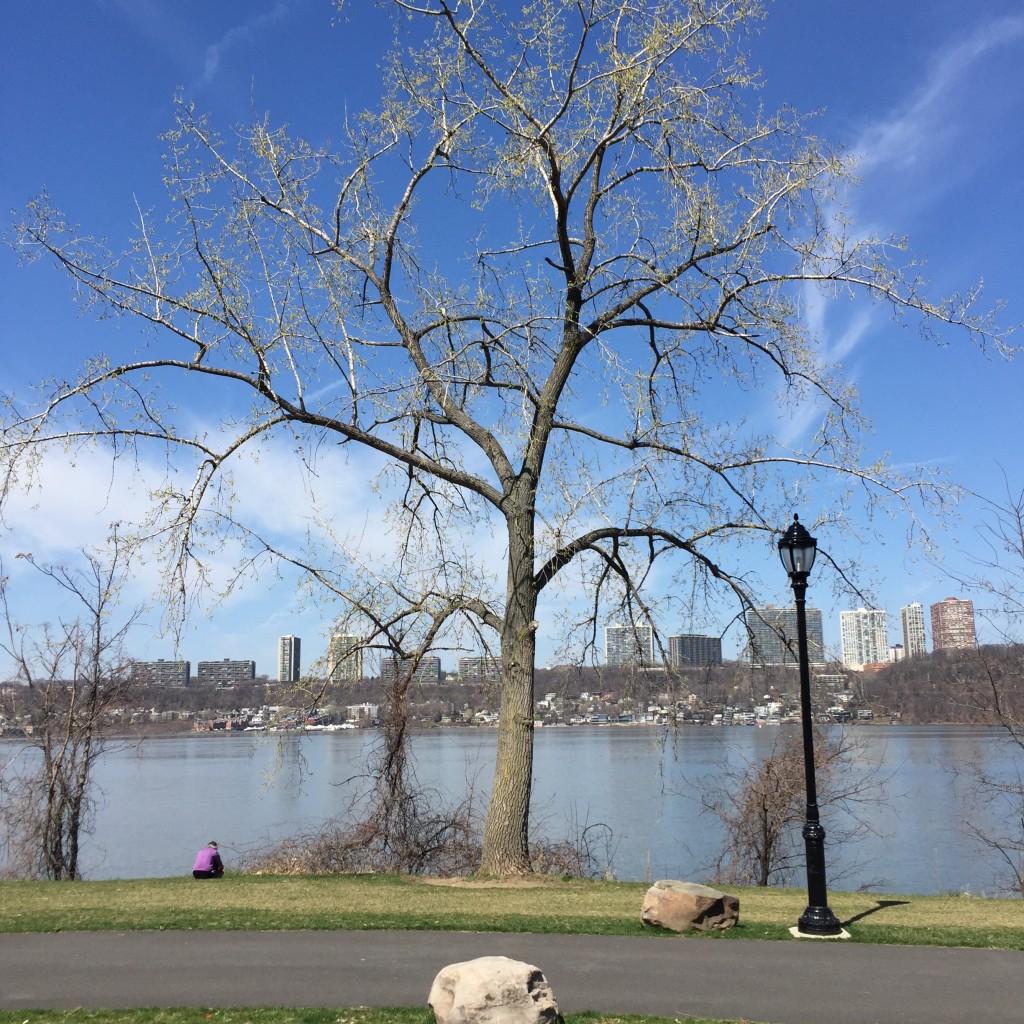

On one of the first warm Saturdays of spring, I folded the now-crisp palm leaves into a bundle, stuffed them into my backpack, and headed down to a park by the river. I brought my 6 year old son along—partly to teach him about a sacred tradition, and partly because he’s good at digging holes.

First, we tried nice spot under a tree, but the dirt was too hard for our tools—the orange plastic shovel and rake he would use at the sandbox later. We found a spot with softer soil down amongst the rocks on the river’s edge. With its evocation of baptism and the life-giving power of water, the Hudson seemed like a fitting resting place for holy relics.

As we began clearing away the beer bottle caps and cigar wrappers and glistening shards of glass, I wondered if this wasn’t such a great idea after all. Heaven only knows what one might find buried in the shallow soil among the rocks along the Hudson River. In my mind, every rock or root that we uncovered was either a disembodied hand or a smuggled packet of heroin.

Not that the Easter story is without its grit. It is a story of a murder, after all, or at least an execution, with real blood and dirt, with corrupt authorities and dirty informants, even people like us, digging through the dirt of an empty grave.

Still, I wondered if this wasn’t a huge sacrilege we were committing as we dug through the remnants of last night’s party.

It was then that my son pulled out at a rock that was particularly stuck, a tennis ball-sized chunk of quartz, and chucked it into the river.

“Hey, we need those rocks to fill it back in,” I said.

“No, we need this hole to be holy,” he said.

“But, if God made that rock, it is holy,” I said. I looked out upon the river, sweeping past us, up into the magnificent Hudson Valley. “All of this is holy.”

Then it dawned on me. Easter isn’t just the story of the holy coming to walk among the unholy. It’s the story of the holy coming to redeem creation, and resurrect what is holy in it, as well.

Who am I to say that there is someplace on this earth—which God Himself created—that is not holy enough for some sacrament?

The dirt was soft between the rocks, so it didn’t take us long to dig down about a foot. I laid the little bundle of leaves at the bottom of the hole.

I said a short prayer, thanking God for sharing this bit of his creation with us as a reminder of his story, then we pushed back in the dirt, smoothing it all over with the back of the shovel.

Our mission accomplished, we brushed off our hands and headed to the playground to play in the sun for the rest of the day.