by Bonnie Anderson and Dan Webster

This movie makes it abundantly clear how deep rooted racism in this country really is.

It’s a sobering look at a piece of Civil War history that’s not widely known. It’s probably a side of Confederate Mississippi many would like to keep quiet. If our nation were a family in therapy, not every family member would want to deal with this part of our history. But we must as families, communities, parishes, dioceses, states and regions if we are to heal the gaping wounds of racism, bigotry and xenophobia.

After seeing a “historical” drama we may wonder which parts of the film were actually true and which parts were invented. In this film there’s no need to wonder. The film’s writer and director, Gary Ross, has made the facts and the inventions perfectly clear in a website where approximately 36 scenes and topics are documented and explained.

The website also provides a source list and access to the actual sources used. This kind of historic accountability to film goers is a “first” in film-making history and sets a pretty high bar for future directors of historical dramas who may choose to leave the audience still wondering about what is real history and what is imaginative license.

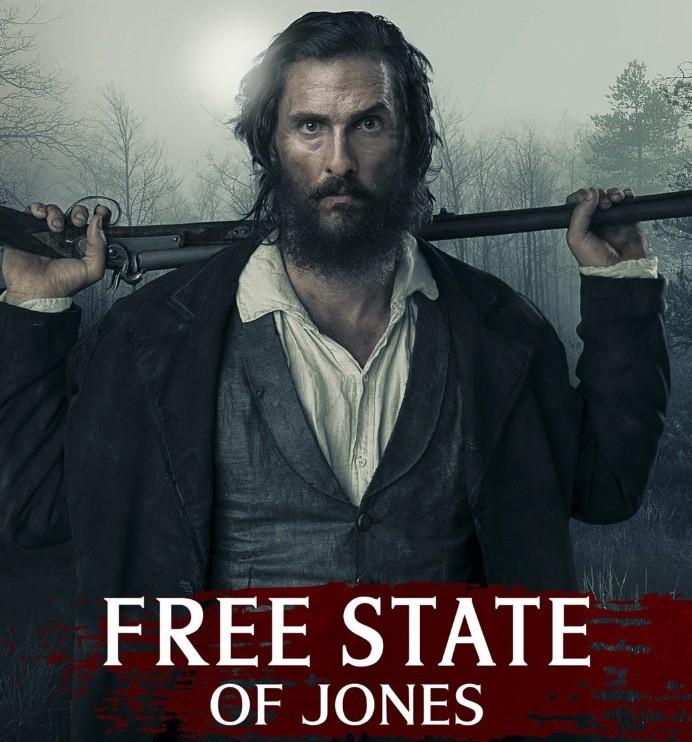

Newton Knight, masterfully played by Matthew McConaughey, leads an uprising against the Confederates. Johnny Reb soldiers are taking crops and livestock to feed the troops. Poor farmers and runaway slaves team up. Knight was an ally to the renegade slaves and we could not help but wonder if he rightly should have had a supporting role instead of the lead.

Knight served as a medic in the Confederate Army but walked away. You may be surprised to learn there were Confederate dissidents, many of whom deserted when learning that sons of plantation owners were exempt from the draft if their fathers owned a certain number of slaves. It was too much to risk their lives to keep the rich, rich. That realization initially prompted Newt Knight too, but soon he became an ally to “run-away” slaves affirming that “you can’t own a child of God”.

The “R” rating reflects the gruesome aspects of this country’s bloodiest war. There’s ample on-screen evidence of the human toll that war took and makes a very good case of the futility of warfare. But the editing between events in the 19th century and how it affected the trial of a Knight descendent in the 20th century is powerful. It shows just how we are a product of our history and the work still necessary to right the wrongs of decades.

God shows up often here. Secessionists and slaves find comfort in words from the Bible. Burying a young boy killed in battle, Knight reads from Psalm 139 as he leads a graveside service. Other scenes quote Scripture and remind us of Abraham Lincoln’s observation that both sides claimed to have God on their side.

The film is poignant, not only for its reminder and illumination of the sins of slavery, but also for its portrayal of the horrific events inflicted on people of color in the south following the Civil War and during “Reconstruction.”

This film’s definitely one our readers should see. After all these years, this film, sadly enough, is timely. Moses Washington (Mahershala Ali) former slave, dissident and register of voters post-Civil War summed it up when he said, “You can’t own a child of God”.

In the current atmosphere of repealing part of the Voting Rights Act, of the disproportionate deaths of young black men and women by police or security guards, of the covert and overt use of racist language in our partisan political life, we would all do well to be reminded where we have been. If we do that we can chart a course to that beloved community the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., talked of so frequently. It’s time we move from dreaming to living free.

Bonnie Anderson is a very active lay leader in her parish, diocese and in the wider Episcopal Church. She is an experienced community organizer and lives in suburban Detroit. Dan Webster is an Episcopal priest in Baltimore, Maryland and a former broadcast news executive. But don’t expect only east coast urban perspectives here. As it turns out, they both grew up in Southern California. They blog about films and faith at Faith Reels