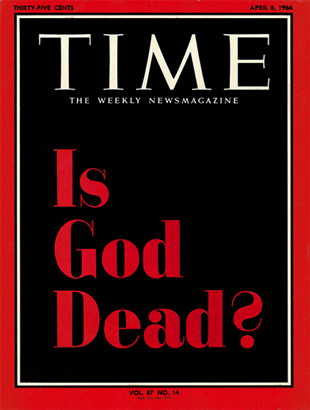

Fifty years ago, Time asked whether the idea of God had run its course and lost any real sense of authority. Reflecting on the rise of communism with its commitment to atheism, the horror of the Holocaust and the workings of the Vatican II, Time wondered if there was any future in the idea of real and relevant God;

Is God dead? It is a question that tantalizes both believers, who perhaps secretly fear that he is, and atheists, who possibly suspect that the answer is no.

Is God dead? The three words represent a summons to reflect on the meaning of existence. No longer is the question the taunting jest of skeptics for whom unbelief is the test of wisdom and for whom Nietzsche is the prophet who gave the right answer a century ago. Even within Christianity, now confidently renewing itself in spirit as well as form, a small band of radical theologians has seriously argued that the churches must accept the fact of God’s death, and get along without him. How does the issue differ from the age-old assertion that God does not and never did exist? Nietzsche’s thesis was that striving, self-centered man had killed God, and that settled that. The current death-of-God group* believes that God is indeed absolutely dead, but proposes to carry on and write a theology without theos, without God. Less radical Christian thinkers hold that at the very least God in the image of man, God sitting in heaven, is dead, and—in the central task of religion today—they seek to imagine and define a God who can touch men’s emotions and engage men’s minds.

If nothing else, the Christian atheists are waking the churches to the brutal reality that the basic premise of faith—the existence of a personal God, who created the world and sustains it with his love—is now subject to profound attack. “What is in question is God himself,” warns German Theologian Heinz Zahrnt, “and the churches are fighting a hard defensive battle, fighting for every inch.” “The basic theological problem today,” says one thinker who has helped define it, Langdon Gilkey of the University of Chicago Divinity School, “is the reality of God.”

Noting that fifty years had passed, the Pew Research Center finds that belief in God has proved more tenacious than the authors of the Time piece had imagined. Much as it was unlikely in 1966 to imagine the end of the Soviet Union, the resilience of faith, especially in Russia and China, seemed to have been beyond their ability to imagine.

According to Pew;

according to our 2014 Religious Landscape Study, nearly nine-in-ten American adults say they believe in God or a universal spirit.

To be sure, the share of people in the United States who say they believe in the Almighty has dropped a bit recently, from 92% in 2007 (when the Center’s first Religious Landscape Study was released) to 89% in 2014. And among the youngest adults surveyed (born between 1990 and 1996), the share of believers is 80%.

In recent years, there also have been small declines in other measures of religious commitment. For instance, between 2007 and 2014, the share of Americans who say they attend church or another house of worship at least once a week has dropped from 39% to 36%. During the same period, the share of Americans who say they pray daily also has dropped 3 percentage points, from 58% to 55%.

To be sure there have been declines in religious commitment, but the question remains to what degree that signals an equally marked decline in belief.

Between 2007 and 2014, for example, the share of Americans who are religiously unaffiliated jumped from about 16% to almost 23% of the adult population. However, it’s also important to point out that a majority of these “nones” (61%) still say they believe in God or a universal spirit.

Is the idea of God wounded, in transition or dying? Time may have been right that some of the more traditional ways of understanding God were falling, but is that due to a growth in understanding on our part maybe or something else?