by Esther Dharmaraj

It is hard not to be spellbound by Paul Thomas Anderson’s disturbingly beautiful Phantom Thread, Daniel Day-Lewis’ mystifyingly memorable Reynolds Jeremiah Woodcock, and Vicky Krieps’ enigmatically sensational Alma. It is a most unconventional, unparalleled older boy meets girl story. Both Woodcock and Alma veer away from the archetypal Mr. Rochester and Jane Eyre, Max De Winter and the second Mrs. De Winter or even Professor Higgins and Eliza Doolittle. They first meet over a long breakfast order, right after he has his sister – played exquisitely by Lesley Manville – depose from the Olympian Hill another young muse who has become a “gloppy” annoyance. Even in Woodcock’s and Alma’s first interaction there is the appearance of equality in spite of the obvious disparity in gender, disposition, age and situation. He is an exacting, middle-aged fashion designer while she is a much younger, charming waitress. She is unnerved by the invasion on her personhood the first time he takes her out to dinner and she fits quite adeptly into the sophisticated, functional Woodcock London home as his muse and more.

Over the course of several fittings for debutants and duchesses and numerous breathtaking sartorial exhibitions, we think, we find Alma at the very brink of the all too familiar fate of women – pilfered and discarded. It seems a crime to refer to buttering toast and pouring tea into cups as grating, but that is how Alma’s breakfast rituals are perceived by the fastidious Woodcock and the writing appears to be on the wall. Is there another quiet send-off with a Woodcock designer gown in the offing? It is at this juncture that the story unveils actions and responses that challenge a more conventional view of love. Through food as a metaphor for love, Alma begins to find and express her language of love and Woodcock begins to partake of it.

While the consensual nature of the giving and receiving of this food of love is suggested, the story-teller leaves the genesis of this particular food deliberately obscure leaving many disturbed and disoriented. It takes a spectacular story-telling to allow characters and their actions to reside in hues of grey, beckoning the audience to be enraptured by the layered and the complex.

Of the various layers the story invites the audience into, I was enraptured by the idea of vulnerability. The story made me think of the indispensable importance of vulnerability in any authentic interaction and meaningful relationship and particularly in any interaction and relationship of intimacy. In a truthful contrast to self-sufficiency that inanely boasts – “I don’t need you,” vulnerability honestly readies one’s being for that which can be received only from another. It is in the awkwardness of vulnerability that some of the most intimate of human experiences are lived. And what lends such a soul-stirring loveliness to this vulnerability is the fact that it is often chosen and not imposed.

Esther J. Dharmaraj lives in Simi Valley, CA with her husband. They are parishioners of St. Francis Episcopal Church. A life-long Anglican/Episcopalian, Esther has a Master’s degree in English Literature from the University of Madras and taught high school English in India before emigrating to the United States of America some ten years ago. She has written for periodicals in India and Stateside. Esther loves a good and thought-provoking yarn.

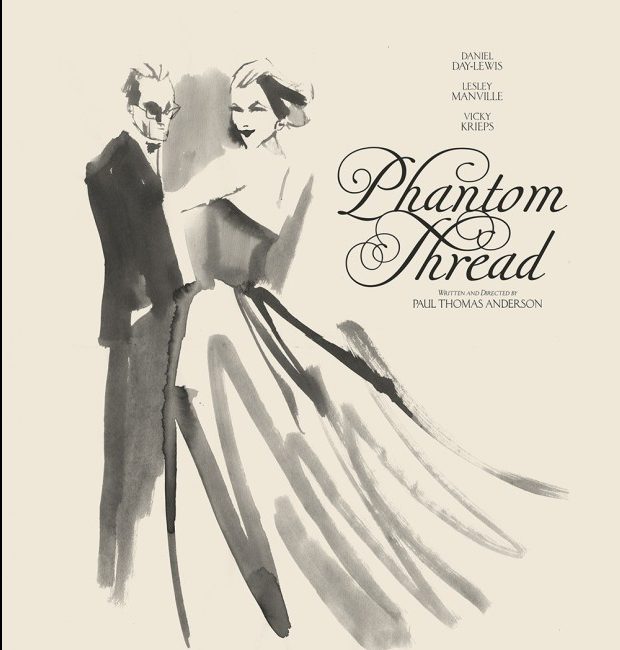

image: alternate movie posters lovingly created by Midnight Marauder & Tony Stella