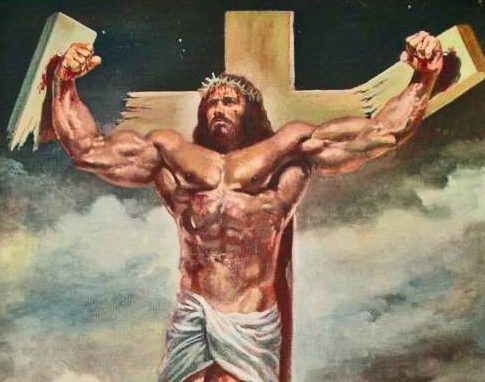

81% of white self-professed Evangelical Christians voted for Donald Trump, which has confounded many who see in Trump’s self-professed sexual assault, multiple divorces and hateful rhetoric values that are anything but Christian. On the website Religion and Politics, historian Kristin Du Mez has a post, Donald Trump and Militant Evangelical Masculinity, that seeks to explain how so many Christians came to see in Trump their potential deliverer. She offers an interesting historical review of the process where over several generations, evangelicals began to frame Jesus and Christianity as hyper-masculine, thus contributing to the rise of Trump.

“The truth is, many evangelicals long ago replaced the suffering servant of Christ with an image that more closely resembles Donald Trump than many would care to admit. They’ve traded a faith that privileges humility and elevates the least of these for one that derides gentleness as the province of wusses. Having replaced the Jesus of the gospels with an idol of machismo, it’s no wonder many have come to think of Trump himself as the nation’s savior.

Indeed, white evangelical support for Trump can be seen as the culmination of a decades-long embrace of militant masculinity, a masculinity that has enshrined patriarchal authority, condoned a callous display of power at home and abroad, and functioned as a linchpin in the political and social worldviews of conservative white evangelicals. In the end, many evangelicals did not vote for Trump despite their beliefs, but because of them.”

She notes that many Christians began to conflate their faith and American patriotism in facing the existential fear of Soviet communism, and feeling that a robust response was needed to protect both the nation and the faith.

“Evangelicals staunchly opposed communism, and their reasons for doing so were many: communists were anti-American, anti-God, and they threatened God-given rights and the integrity of the family. A strong military was necessary to ward off the communist peril, and strong men were essential to a strong military.”

But the war in Vietnam created a conflict, because as it degenerated into a confused quagmire and domestic opposition increased, evangelicals felt that their faith was threatened by the various social justice movements of the 1960’s and they began to see upholding traditional gender roles as a Christian imperative;

“But the rising generation caused reason for concern. Young men sporting long hair and flowered shirts dodged the draft, shunned authority, and shirked their duty to protect America from the threat of global communism. The Vietnam era would emerge as a pivotal moment in the relationship between American evangelicals and the U.S. military. In the 1940s and 1950s, evangelicals had often looked askance at the military, which they saw as a source of moral corruption for young men. But as Anne Loveland has argued, evangelicals who supported U.S. military action in Vietnam came to hold the military itself in high (and often uncritical) esteem.”

The end of the Cold War might have seemed to undermine the basis of this movement, but the changing economy that lessened the ability of families to get by on a single (male) wage earners salary created anxieties that were then bolstered by the emergence of a widespread fear of terrorism in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

“The moral certitudes of the “War on Terror”—framed by evangelical president George W. Bush—abruptly replaced the post-Cold War malaise. Once again America needed strong, heroic men to defend the country, at home and abroad.

Evangelicals, many of whom had never strayed from Cold War gender constructions, stood at the ready to address these new conditions. “When those two planes hit the Twin Towers on September 11, what we suddenly needed were masculine men,” Farrar wrote in his 2005 book King Me. “Feminized men don’t walk into burning buildings. But masculine men do. That’s why God created men to be masculine.” In no uncertain terms he repudiated the earlier “Tender Warrior” motif: “The trend today is to major on the ‘tender’ and minor on the ‘warrior,’” but “in the trenches you don’t want tenderness.”

It is not difficult to imagine how evangelicals, steeped in literature claiming that men were created in the image of a warrior God, might be receptive to sentiments like those expressed by the late Jerry Falwell, in his 2004 sermon “God is Pro-War.” In fact, surveys demonstrate that traditionalist evangelicals are more likely than other Americans to approve of U.S. engagement in a preemptive war, support military action against terrorism, and condone the use of torture.”

It is into this stew of hyper-masculinity and sense of existential dread into which walked Donald Trump, with many evangelicals seeing in him, the embodiment of the tough, no-nonsense aggressive leader who could lead the people out of their perceived chaos.

“This brand of militant masculinity also helps explain the lack of outrage on the part of many evangelicals when it comes to Trump’s character issues. Dobson himself, one of Trump’s most influential evangelical supporters, urged fellow Christians “to cut him some slack.”* More tellingly, the Rev. Robert Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas and stalwart Trump supporter, explained his endorsement of the unconventional candidate in this way: “I want the meanest, toughest, son-of-a-you-know-what I can find in that role, and I think that’s where many evangelicals are.””

It’s important to remember that the hatefulness and bigotry that has followed in the wake of Trumps campaign and election, regardless of Trump’s personal beliefs or intentions, are rooted in our history and that it is this underlying fear and paranoia that the Gospel is meant to confront.