A class discussion during the first week of my second semester of seminary left me feeling unsettled. One of my classmates nonchalantly remarked that she was attending seminary to search for mental and spiritual healing. Several classmates quickly echoed her sentiments. I dissented. I was not attending seminary to work on personal issues. Instead, I had reluctantly concluded that God was calling me to ordained ministry because that ministry was how I could do the most to make the world a more just, peaceful place. Seminary, I hoped, would provide the knowledge and skills to equip me for effective ministry.

At some points in the conversation, I sensed that at least a few of my classmates regarded personal brokenness as a prerequisite for ministry. That idea conflicted with my self-image. Although I have never considered myself perfect or whole, I still had enough self-awareness and confidence to recognize that I, a child of privilege with reasonably good health, had the relational competence, education, and marketable skills to live well without attending seminary. My understanding of call emphasized service and not self. Any personal benefits that might accrue from ministry seemed incidental rather than essential.

My efforts to convince my seminary classmates that Jesus’ power to heal the sick was not dependent upon Jesus’ being ill or broken failed. I have occasionally wondered what happened to my classmate who attended to seminary to find healing. I hope she found the path to health that she sought without becoming an unintentional source of hurt for others.

However, during almost four decades spent in collegial ministry, much of it in a supervisory capacity, I almost inevitably observed problems when the sick tried to heal the sick. Sometimes it worked. Most often, it ended in tragedy, e.g., as occurred in the ministries of a former Suffragan Bishop of Maryland and that of a gifted colleague at the Naval Academy who was arrested for public indecency.

Thankfully, effective ministry does not require health, wholeness, or perfection. If it did, the Church would not have any ministers, lay or ordained. Nevertheless, effective ministry requires awareness of one’s disease(s), brokenness, or imperfection while having sufficient health (1) to set and keep appropriate boundaries to avoid harming others, (2) to be a channel of the grace that heals self and others, and (3) to be an icon in and through which others meet God.

Twenty years ago, a laicized Roman Catholic priest, a former vocation director for his diocese, told me that a major reason he had left the priesthood was that his superiors, faced with declining vocations and desperately needing priests, repeatedly lowered the standards of candidates for holy orders. This became intolerable when his superiors directed him to accept candidates they knew had serious mental health problems.

Pressures to accept individuals and move them through the ordination process are growing in The Episcopal Church (TEC). Even though TEC currently has no shortage of clergy, too few are willing to serve small congregations, particularly in rural or geographically remote areas. Consequently, some dioceses are developing alternative ordination paths. Hopefully, these dioceses will maintain TEC’s historic insistence on refusing to ordain those with significant mental, physical, and spiritual impairments. Admittedly, TEC’s screening never identified every troubled individual; furthermore, clergy sometimes develop problems after ordination. Yet the process, as I know from watching hundreds of chaplains from faith groups without similar screening requirements, is essential for safeguarding the health of the Church and well-being of its members. Concurrently, a few diocesan ordination processes appear reluctant to impose stringent requirements for mental, physical, and spiritual health on putative ordinands, wanting to honor the call the individual and sponsors think that they have heard.

TEC’s continuing numerical decline will inevitably increase pressures to generate ordinands. Ironically, the necessity of ensuring healthy ordinands varies inversely with institutional health. A more stable, institutionally flourishing Church has far greater capacity for identifying clergy with problems, minimizing the harm those individuals can do, and guiding them into wellness programs and positions that provide close supervision. A weaker institution has less resilience, less capacity for averting harm from dysfunctionality, and more pressure to accept aspirants.

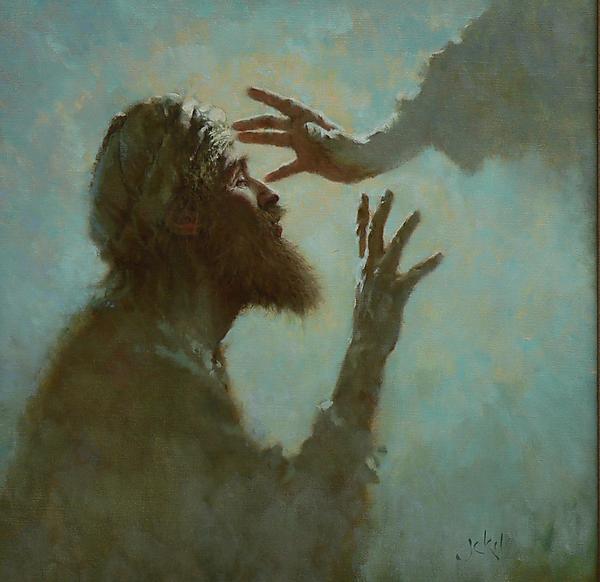

My sporadic, though continuing, reflection on classmates’ explanation that they attended seminary to find healing has deepened my appreciation for metaphors about Jesus that connect brokenness and ministry. Brokenness in these metaphors does not connote illness or imperfection. Illness and imperfection may help a minister to stay grounded in his/her humanity, reveal the minister’s need for healing, and encourage awareness that s/he journeys as a fellow pilgrim. But this brokenness can never displace or replace God as the source of healing.

Instead, brokenness in metaphors that connect brokenness and ministry connotes Jesus giving himself in love to us: his life poured out (spent) for us; his wounds (physical and emotional pain suffered because of his uncompromising love) being a source of healing for us; his emptying himself (becoming human) that we might become whole. Through his being broken for us (both his passion and in Holy Communion), we enter into the health of his wholeness. God’s love flowed then and now through Jesus to heal the sick and restore the broken to life.

My ongoing prayer asks that I may be broken (spent, emptied, or poured out) so that the love of God and neighbor may increase. In living into that prayer, I have experienced life, love, and God more deeply than I could have imagined when a seminarian.

George Clifford is an ethicist and retired priest in Honolulu, HI. He served as a Navy chaplain for twenty-four years, recently authored Just Counterterrorism, and blogs at Ethical Musings.