by Kathy Staudt

I have been teaching in a forum series locally on the theme “Why Be a Christian,” and in the course of that I’ve been digging a little deeper into Presiding Bishop Michael Curry’s efforts to call the Episcopal Church back to our identity as a “Jesus movement,” even as I’ve been surprised and a little dismayed by many “liberal” Episcopalians who confess they have “trouble with the Jesus part.”

When I teach about Christian spirituality I often remind people that at least in the historical tradition, when Christians talk about “following Jesus” they mean not only following precepts of a great Wisdom teacher, which Jesus certainly was, historically, but about following and knowing the post-Resurrection Jesus, experiencing the holy through our experience of the Living Christ who promised to be with us always, to the end of the age (Matthew 28:20)

But I think that Episcopalians and others who identify as mainline Protestants or “progressives” have been shy about Jesus-language, largely because of the way that self-identified conservative Evangelicals have emphasized as normative a “belief in Jesus Christ as personal Savior”, but tying that to a highly individualistic theology that tends to emphasize personal salvation from damnation, fear of judgment, and conformity to community norms that are considered “Biblical” through a fundamentalist lens.

A watchword of “liberal” Christianity, beginning with Harry Emerson Fosdick and picked up by Verna Dozier and Bishop Michael Curry among others, is that we need to learn to “follow Jesus, not worship Him.” I would be on board with this if we added “follow Jesus, not just worship Him,” but my experience tells me that the energy that allows us to follow Jesus’s teachings comes from a more mysterious place that the tradition has named as the work of the Holy Spirit or as the encounter with the Living Christ. We not only follow the teachings of our great Wisdom Teacher; we seek to be empowered, through prayer, worship, and spiritual practice, by the God who desires New Life for all of Creation, who was Incarnate in Jesus. We are called both to follow Jesus and to worship together, to embrace the mystery of the divine life, in which His story invites all Creation to participate. This is what our sacramental tradition affirms when we call ourselves “living members of our. . . Savior Jesus Christ” – sent “to do the work you have given us to do, to love and serve you as faithful witnesses of Christ our Lord”) as our prayer book has it (BCP. 365-6).

As I explored “Jesus movements” of the 20th century I came to realize that I myself am a product of the revival of a Jesus-focus that we saw in the US in the 1960’s and 1970s, expressed in the “Jesus people” of hippie culture, in the charismatic revivals in the Roman and Episcopal churches, in the strengthening of movements like Intervarsity and Campus Crusade for Christ, and also – strikingly – in movements like Sojourners and Call to Renewal that persist in tapping the energy of the Living Christ to build “base communities” dedicated to the service of the poor and work for social justice.

Looking at “Jesus movements” in the Christian tradition, we can see that across the political spectrum, times of revival have come with the invitation to embrace a relationship with the Living Christ. So the progressively oriented Social Gospel movement of the turn of the 20th century was powered in part by the question “What would Jesus do?” – a question nourished by deeply personal prayer. Jesuit spirituality invites companionship with Jesus as we discern our path for life, and Franciscan spirituality embraces the God of Creation incarnate in the humble Child, calling Christians to a life of following Jesus that embraces Poverty of Spirit. These are spiritual traditions that have been available to what our culture labels as “liberal” or “progressive” politics – but the Church often seems disconnected from these rich resources in our tradition, even when the words of our liturgy and hymnody invoke them.

I think we Episcopalians and liberal Protestants have become shy about embracing a relationship with the Living Christ because we have ceded language about “following Jesus” – even the word “discipleship”– to the theological discourse of American fundamentalist evangelical Christianity. And the reasons for this divide have deeper theological and cultural roots that I’ve uncovered in looking at my own journey of faith, which is very much “Jesus centered” though I’ve often been shy about using that language in Episcopalian circles: I want us to get over this shyness. But here’s my story. My testimony, if you will.

I came into the Episcopal Church as a young adult in the mid-1970s, playing my guitar for the student chapter service at St. John’s Northampton, on the campus of Smith College. I learned not only the early folk masses of Ian Mitchell (now largely forgotten) but also many of the songs that energized my evangelical friends who attended the Thursday Eucharist and were also active in Campus Crusade for Christ. In fact, part of what drew me back to active involvement in Church was the way I experienced, in one of my evangelical friends, a person who clearly lived into and took great joy in an ongoing, prayerful relationship with Jesus. Just being in her presence was transformative. We differed theologically on a lot of things (I’ll get to that in a minute) but there was a core experience that attracted me, and that I came to find in the celebrations of Eucharist at St. John’s – affirmed in the new liturgical language that we were using and in the conversations we had in small groups about what this all meant for our lives. But it was about experience at first, not doctrine or belief. And that experience was about Jesus, though because of the excesses of my Evangelical friends I gradually became more shy about claiming my experience in that language. Luckily the Eucharistic prayers named it every time and gave me language that worked for me.

As I looked for a fuller theological framework I was particularly interested in the songs that everyone brought, songs that carried the energy of joyful spiritual experience. Two songs that friends sang with their guitars now strike me, as I look back, as reflecting 2 paths that the “Jesus movements” of the 1970s have taken – and have given me a clearer picture of the path we are called to follow now, and the theology that we need to embrace more explicitly if we are to reclaim our voice as Christians in the public square in this time.

The first song I learned, I Wish We’d all Been Ready epitomizes a theology of salvation and an eschatology that became dominant among many of the “Jesus people” movements of the 70s, especially those rooted in Pentecostal and charismatic traditions that were already focused on fear of damnation and the need to save souls. The lyric included these words: “Life was filled with guns and war/And all of us got trampled on the floor/ I wish we’d all been ready. . . there’s no time to change your mind. The Son has come and you’ve been left behind.” Friends who liked this song, many of them active in Campus Crusade for Christ, were what theologians call “premillenialists,” a tradition that became strong in the late 19th century in this country and that saw us as living in the “end times” dominated by Satan, and awaiting the imminent return of Christ to judge the world. This view has been enshrined more recently in the very popular Left Behind series books by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, and the growing popularity of this movement reflects a view of the social order and of political engagement that many of us who identify as “progressives” find both troubling and “un-Christian.” But in this world view, if the Rapture is coming, there is nothing to be done about the decay of the social order; the important thing is to rescue as many souls as possible from the judgment to come; and faithful Evangelicals have viewed this as a work of love – to save lost souls. Working to protect the environment or being concerned for future generations, in this scenario, is not worth the effort. It is in fact a distraction from the work of saving souls. : But the comfort of a relationship with Jesus is sustaining to people and so church life remains important in this continuing tradition. Interestingly, this premillennialist view has become more normative in many communities since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1947, which many have seen as a sign of the imminence of the “end times.”

Of course, people outside a conservative Evangelical community experience this message as harsh and exclusionary and many people associate this brand of Christianity with “Jesus movements.” I remember students I taught at the university level who believed that the basic message of Christianity was “if you don’t agree with us you will be damned.” And the name of Jesus was associated with this message.

But the other song we sang together, both at St. John’s and at Campus Crusade Bible studies, was “They’ll know we are Christians by our Love” – part of whose lyric goes “We will walk with each other, we will walk hand in hand, and together we’ll spread the news that God is in our land; we will work with each other, we will work side by side, and we’ll guard each one’s dignity and save each one’s pride.” This represents what theologians call a “postmillennialist” framework, which has been the dominant Christian view beginning with the gospels: the view that with the coming of Jesus, the promised restoration of the reign of God has begun, and the work of Jesus’ followers, empowered by the Holy Spirit and the presence of the Risen Lord, is to support the emergence of that reign through a devotion to intentional community, peace and justice. The Church begins and continues the “Jesus Movement” – carrying on the reconciling work of the Risen Christ in the world.

Many of us with a postmillennialist view of the coming of the Reign of God have become shy about invoking the name of Jesus because of its associations for people who have been wounded and excluded: but think about the gospel and Jesus’ practices of inclusion: should we surrender this core of our faith tradition just because we share it in common with a theological tradition about the end times that we reject? I believe we need to be aware of this fundamental difference in theological frameworks, and perhaps even name it more explicitly, when we claim the authority of Jesus for the work of social justice

The Presiding Bishop’s call to be “crazy Christians,” to “turn the world upside down,” to claim the “Jesus Movement” title is challenging for the reasons I’ve laid out but I believe it is the energizing call that we need. What would it look like, in our formation work, in preaching, in explaining and practicing liturgical and personal prayer, in testifying to our own experiences of the Living Christ, to be more explicit about our own theology of the unfolding reign of God and how it is distinct from other ways of being Christian. We have some eloquent contemporary voices defending this view in accessible language – think of the work of Brian McLaren, Jim Wallis, Cynthia Bourgeault, Marcus Borg, Phyllis Tickle, Richard Rohr and Ilia Delio among many others. The spirituality we are claiming transcends political categories like “liberal” or “progressive” though it may often intersect with those positions. But surely the current political climate underscores both the importance and gift of the teachings and the sustaining spiritual presence of the Living Christ, however named, in our life as the Church. I hope that we can claim this vision unapologetically and with boldness. This is our way of being Christian, and it is a life-giving way.

Dr. Kathleen Henderson Staudt keeps the blog poetproph. She works as a teacher, poet, spiritual director and retreat leader in the Washington DC area and is the author of two books of poetry: “Annunciations, Poems out of Scripture” and “Waving Back:Poems of mothering life”, as well as a scholarly study of the modern artist and poet David Jones.

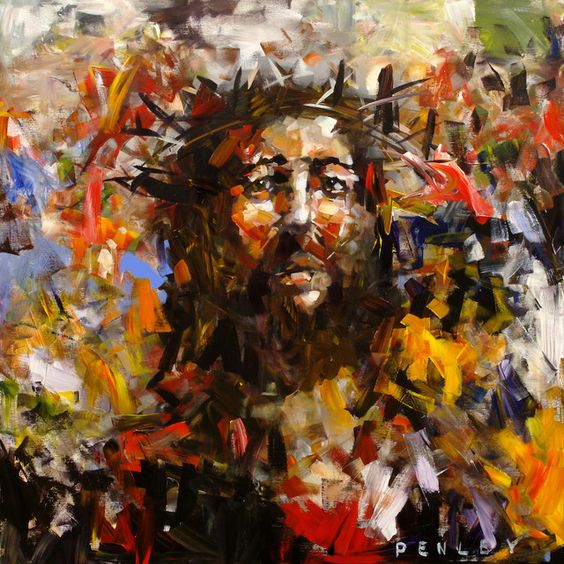

image: Jesus Christ by Steve Penley