The Magazine

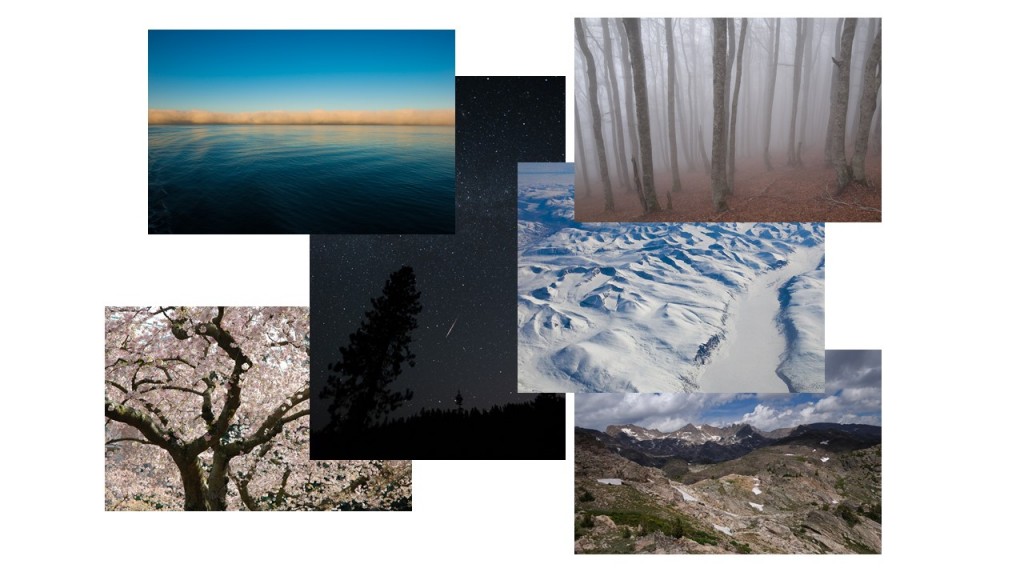

Photo essay by Jim Friedrich

Perseid meteor shower, east side of Washington’s Cascade mountains (2013)

The very term “Creation” implies a theological view. The universe of matter and energy is something created, something given. We didn’t produce it ourselves. We don’t own it. We receive it, all of it, including our own being and self-awareness. This foundational reality is sometimes lost amid the personal and social constructions of habitual life, but it is always recoverable. Just go outside and look at the stars. In this case I drove 100 miles over the Cascade mountains east of Seattle to find a forest road free of light pollution during the Perseid meteor shower of August 2013. Did I feel small under such a sky? Only if I were to insist on my own separateness. The glory of the heavens is participatory. It’s a dance, and we’re all in it.

Fog bank, Puget Sound (2014)

The Creation in Genesis 1 is founded on difference. The first day introduces light into the singularity of darkness. On the second day, God divides the water below from the infinite Beyond with the interposition of sky. And everything since has been a matter of this or that, here and there, yes and no. The Creator has such a penchant for difference! But when it comes to human and divine, God has blurred the boundary, allowing the opposites to mix rather freely. Just so does this fog bank in Puget Sound – a theophanic image for me of the Cloud of Unknowing – simultaneously accent and obscure the division between sea and sky, earth and heaven.

Greenland from 35,000′ (2014)

Thoreau once said of a remote Canadian lake that to be aware of its existence, though he himself would never get there, cheered him enormously. Simply to hear its name assured him that there were “oases of wildness in the desert of our civilization.” Without such wildness, the world – and the soul – would soon be exhausted and reduced to sterility. This alien landscape of glacial ice, photographed with my phone from an airplane somewhere over Greenland, generates for me a similar sense of wild immensity. Walking upon it is an experience I will never “collect.” But my spirit soars to know it is there. But for how long?

Beartooth Mountains, Montana (2014)

In the ancient world, the orderliness of creation was a dominant theme in both pagan and Judeo-Christian thought. God was a skilled craftsperson, and the earth, created for sustainable human dwelling, was the product of benevolent design. The wild unruliness of mountain landscapes, unsightly jumbles of rocks beset by inhospitable storms, were problematic for civilized theorists well into the seventeenth century. Occasional prophets and mystics would venture into the high country to overhear the news from heaven, but it wasn’t until the Romantics that we really fell in love with mountains. We now find it renewing, not threatening, to wander a terrain which we can neither exploit nor tame, but only contemplate and enjoy. Like God’s own self, the otherness of mountains releases us from egocentricity. A day spent among the clouds in an alpine ramble is not deducted from our allotted span. Rather, as John Muir said, it makes us “rich forever.”

Beech forest, Camino de Santiago west of Roncesvalles (2014)

What is the forest trying to tell us? It has haunted human imagination ever since our primeval ancestors abandoned the world of trees for the open skies of savannah grasslands. The shadowy sylvan world we left behind became the abode of myths and projections, dreams and fears. Pathless and wild, the forest (from foris, meaning outside) represented the antithesis of civilized order, the dark wood where the traveler is soon lost. It could be the dangerous abode of outlaws and demons, or a place of refuge and escape. The vast wooded expanses of prehistory, where a squirrel could travel a thousand miles without touching the ground, have long since been cut down to make room for agriculture and human settlements. What remains, like this beech forest in the Spanish Pyrenees – one of the largest remaining in Europe – still has the power to enchant, even as it poses urgent questions about the physical and spiritual consequences of deforestation.

Cherry tree, University of Washington (2007)

The Yoshino cherry trees on the quad of the University of Washington are the Hallelujah chorus of a Seattle spring. The annual eruption of fresh color after the winter drab has been an irresistible metaphor of resurrection for hymn writers and altar guilds since ancient times. Theologians may caution us not to confuse nature and revelation. Christ’s resurrection stands uniquely apart from the vegetative cycle of death and rebirth. But who can resist the festive bloom all around us at Easter? Even Jesus used a nature metaphor, the grain of wheat that dies to become fruitful, to describe the Paschal Mystery. And I’m pretty sure these cherry blossoms give the Author of Life particular pleasure.

The Rev. Jim Friedrich is a liturgical innovator, filmmaker, photographer, musician, storyteller, teacher and writer. He is a lifelong Episcopalian: his first church was a movie theater and his second was a stable. He wrote and produced award-winning videos on “The Story of the Episcopal Church” and “The Story of Anglicanism.” He lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington, and blogs as The Religious Imagineer at http://jimfriedrich.com/.