by Aloysius Peter Thaddeus, Jr. J.D.,

It has happened to me, and I’m pretty sure it has happened to most people in the last 18 months. There you are talking to your neighbor, or a somebody at work, or maybe somebody you have sat next to at church for the last 20 years and it happened! Once upon a time they were rational, reasonable, and steady people and suddenly they lose their mind right in front of you. And when it happened you turned your head to look at little closer at your once sane friend. Then you take a step back, “What did you say?” you ask.

Now all you did was make the tiniest joke about some event connected to a political figure running for the highest office in the land. The response was faster than texting teenager: “That’s fake news from that hijab wearing, Muslim loving godless baby killer of doubtless parentage!” or “That’s fake news from that raciest, narcissistic, lying, lecherous Cotton-Headed Ninny muggings!” (I paraphrase.)

It happens on the internet, especially on the internet. People you know who usually post pictures of little girl tea parties in fields of blue bonnets with bunnies scampering about on their Facebook page were now reposting stories with headlines like “Candidate so and charged with six space alien registered sex offenders for operating a marijuana farm in an East Texas Corn Maze.” My last attempt at engagement on social media was posting this question: Regardless of how the election turns out, how are we going to go forward as members of the body of Christ? The first reply post I received was from a longtime acquaintance with whom I had shared many meals in his home: “You better watch it, if ______ wins you’ll be living under Sharia Law,” was his reply.

That was it. There was no way to have a thoughtful discourse on the course of Christianity in social media. What in heavens name happened to these people? I am in Seminary and a postulant for Holy Orders. I cannot avoid the question. The question remains for me, for us, as a Christian: How do we love our neighbor as ourselves in the face of a polarized world and church?

I recently read a church news interview with some clergy on how they handle preaching in a parish with widely different views. One priest was quoted as saying “So, Scripture becomes a kind of grounding that you have to keep submitting yourself to – to the claims of the text – so that you are staying in contact with God as the source of preaching.” Another was quoted “It’s another thing to ask how are we as gospel people to embody our lives now. How are we to enact gospel witness? …[P]reachers have to cast a larger vision of “justice, forgiveness and God’s love.” That’s good. Could there be more?

In the same church news story Presiding Bishop Curry observed “It can be pastorally helpful to actually talk about something that everybody’s thinking about but afraid to voice,” Curry said the next question is “how do you move forward and offer a word and help people navigate a context that is complex – morally complex?” Brave words. How many of us have the faith to be that brave?

I came across this blog post in a class assignment by Charles Eisenstein written just after the election, “We’ve got to stop acting out hate. I see no less of it in the liberal media than I do in the right- wing. … I think the pain beneath is fundamentally the same pain that animates misogyny and racism – hate in a different form. Please stop thinking you are better than these people! We are all victims of the same world-dominating machine, suffering different mutations of the same wound of separation. Something hurts in there.”

Eisenstein is not advocating for a withdrawal from political conversation. Instead he says we need to change vocabulary. It is one thing he says to speak hard truths but we have to uncouple those from the inevitable “Aren’t those people horrible?” follow up comment. If we don’t, he says we are accepting an invitation to dark side. Eisenstein suggests we put aside that judgment like language and engage those we vehemently disagree with a plain inquiry. We don’t we just ask someone why think the way they do?

I think Eisenstein is on to a good thing. For many years, I was privileged to practice law and had license to question people who were almost always hostile, if not directly to me, then my client. What I found to work for me when questioning folks is to ask “why”. Not to cross examine them. But ask, why were you suing my client? Or why do you think this happened this way? Or why do you feel that way? This seemed to engender a human response akin to “Thanks for asking, let me explain”. I was given the opportunity to see a different point of view.

But back to Eisenstein. Usually, those evangelizing compassion do not write about politics, and sometimes they veer into passivity. We need to confront an unjust, ecocidal system. …We must not shy away from those confrontations. I see the question as staying engaged instead of enraged.

“To love your neighbor as yourself means not only to love the person whom the legislation was trying to help but it’s also about loving the person who disagrees with you, Bishop Curry says, Republicans and Democrats must see each as neighbors, as defined by Jesus, “if you want to be a Christian,” he said. “The truth is we are not the Republican Party at prayer and we are not the Democratic Party at prayer,” he said. “We are the Jesus Movement and that makes a difference.”

So how do we change? How do we follow the great commandment to love our neighbor as ourselves? How do we engage as a Christians? I don’t the know solution to this polarization. A change in perspective can change your point of view. What all this suggests to me is that we need to change our perspective. One way to respond as a Christian is for each of us to engage in a new spiritual practices that address how we relate to people on the other side of the opinion spectrum? One spiritual practice could be that when we meet somebody who has an opinion different from our own, that rather than confrontation, we try and see the world through the eyes of the person by asking why they see the world the way they see it. Rather than confrontation with that person with your own opinion, ask them what the world looks like from the where they sit. Ask them how they see the world. Try to understand why they believe what they believe.

Another spiritual practice we engage in begins with remembering that we are all created in the image of God. Once you recall that, then imagine that every person you could be Jesus. If you do that sincerely, I believe you will change your perspective about that person. And once you change your perspective, you will likely change your point of view and begin to see them more clearly.

As my seminarian colleague and friend Katherine Harper told me recently, “We are beautifully broken people and complicated human beings.” Would it not be worth it understand each other just a little better.

Aloysius Peter Thaddeus, Jr. J.D., is a Postulant for Holy Orders, Episcopal Diocese of West Texas, and Masters of Divinity candidate, Episcopal Theological Seminary of the Southwest

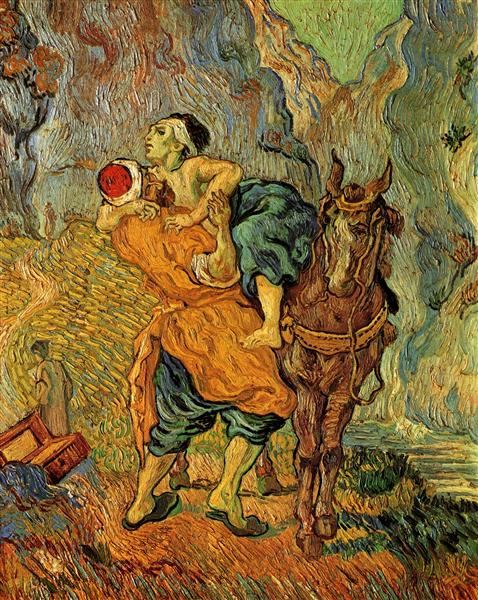

image: The Good Samaritan, after Delacroix by Vincent Van Gogh