By George Clifford

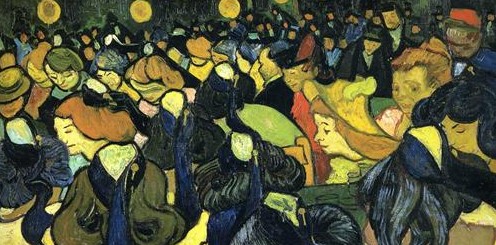

Zorba the Greek tells the story of an uptight Englishman who visits an Aegean island where, after several emotionally traumatic experiences, his last big hope for economic success collapses. Faced with complete catastrophe, he doesn’t cry, whine, or curse God. Instead, he turns to his earthy guide to Greek village life and says, “Zorba, teach me to dance.”

Religious rituals teach us to dance with God. For many Episcopalians, the shape of our Sunday rituals changed dramatically with the adoption of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer. Holy Communion replaced Morning Prayer as the usual Sunday worship service.

Reflecting on my spiritual journey set in the broader context of American culture, two dynamics seem to have had significant roles in bringing the change about. First, I (and many others) sought a greater emphasis on community to balance an unhealthy cultural bias in favor of individualism. Morning Prayer too easily accommodated individualism, permitting attendees to avoid personal interaction. Passing the Peace during Holy Communion at least required attendees to pretend to interact as they mumbled greetings and perhaps shook hands. In the congregations with which I’m familiar, resistance to the Peace has gradually yielded to attendees learning to value a few moments to interact with other worshipers. The ritual of the Peace developed from being an awkward interruption of individual worship to an affirmation (sometimes even a celebration) of our communal identity and worship.

Second, the scientific materialism and philosophical reductionism that permeates our culture has made the inadequacy of words for communicating transcendent realities increasingly apparent. Shifting from Morning Prayer to Holy Communion better balanced the cognitive content of our worship services with greater emphasis on both affect and physical engagement. In addition to the listening, verbal responses, singing, and posture changes called for in Morning Prayer, Holy Communion involves eating/drinking, touch with other people, and movement (at least to and from the altar). Congregations that use incense also enlist the olfactory sense. Drawing people more deeply into the ritual has the potential to draw people more deeply into the transcendent mystery of God’s presence.

Kathleen Norris in The Cloister Walk described the power of rituals to bind a community together and to bind individuals into a community. She memorably illustrated that power with her observations of a Benedictine monastic community.

I repeatedly observed the same power of ritual in my ministry, a binding that occurred more rapidly in transient military communities and more slowly in civilian communities. People acquired the local rhythms through repetition while they concurrently learned the local stories that imbued those rhythms with meaning. Rituals formed individuals into a community, giving their lives meaning.

Paul Tillich insisted that ritual, including the associated story or myth, requires continual reformation and renewal for the ritual to remain vital. I don’t foresee an end to ritual. The search for meaning is basic to the human condition. However, I suspect that the Church will mostly shift from a highly stylized form of Eucharist meal toward a more casual, fuller meal format (this is already happening in some places). I expect that the number of people who find traditional Christian theological formulations satisfying will continue to diminish while the number attracted to post-theistic narratives continues to increase.

Acknowledging the pervasiveness and accelerating pace of change has become so commonplace as to be trite. A Christianity that attempts to remain static, desperately clinging to its current ritual forms and theological formulations, is dying. Refusing to change is tantamount to issuing an ecclesial do not resuscitate order.

Thankfully, the patient is not terminally ill. Christianity need not die. But it is like the uptight Englishman in Zorba the Greek after his repeated setbacks. Time is becoming critical. The Church needs to change and to keep changing at a faster pace if it is to stay alive. What will be our next dance, when will we learn it, and who will be our guide?

George Clifford is an ethicist and Priest Associate at the Church of the Nativity, Raleigh, NC. He retired from the Navy after serving as a chaplain for twenty-four years, recently authored Just Counterterrorism, and blogs at Ethical Musings.