Which of these metaphors—out of step or marching to a different drummer—best describes the Church?

Personally, I want the Church to march to a different drummer. The drumbeat that we hopefully seek to hear is the drumbeat of God’s Spirit calling us to embody a radically Christian ethic. In particular, the Church follows in Jesus’ footsteps by incarnating an ethic of love and care for creation; that is, practicing a radical hospitality that welcomes all equally and simpler living.

Marching to a different drummer does not connote Christian superiority or exclusivity. Instead, the metaphor connotes Christian uniqueness, rooted in the gospel of Jesus, yet affirming of others who march to their own drummers, following other paths to God, perhaps sometimes intersecting or even sharing the Jesus path.

Marching to a different drummer also does not connote a militant understanding of the gospel. I chose the metaphor in spite of that unfortunate association because the metaphor resonates with my lengthy military service and because of our cultural familiarity with it.

However, I’m afraid that too often we equate the metaphor of being out of step with that of marching to a different drummer. On the one hand, I want the Church to be out of step with our social context because we hear a different drummer (that is, God’s Spirit) and live in ways that constructively differentiate us from others. Unfortunately, statistical evidence relevant to that claim is decidedly mixed. For example, Christians live longer but may have a higher divorce rate.

On the other hand, I don’t want the Church to be out of step with our social context because we have become fixated on adiaphora, indifferent things of no ultimate value. Each year, Christmas decorations, music, and advertising appear earlier than they did the previous year. Each year, I hear Christian lamentations about rushing the Christmas season, skipping Advent, and ignoring Thanksgiving. This year, I suddenly realized that these laments are all about adiaphora.

Giving thanks is good, but the holiday of Thanksgiving, regardless of its origin, is really a civic rather than religious feast. I use the word feast intentionally: the average American consumes 4500 calories at Thanksgiving dinner. Interest in sporting events and shopping dwarfs interest in thanking God for one’s blessings. Surveys show that fewer than half of all Americans who eat Thanksgiving dinner take time to express their gratitude to God or one another.

The Bible is silent about Advent. The Church created Advent as a season of preparation for its celebration of Jesus’ birth. Why have four weeks of Advent? Why not have eight weeks? Maybe the season of Christmas should begin the Sunday after All Saints’ Day and culminate on December 25. We could then celebrate Epiphany the following Sunday. After all, the early Church took a pagan feast and baptized it, transforming it into the feast of Jesus’ nativity. Those early Christians recognized that marching to a different drummer does not always require being out of step with society.

Changing the ecclesiastical year, especially in a Church like ours, would require overcoming significant inertia and major administrative hurdles. The Church, by getting in step with when its neighbors start talking about Christmas, might seem more relevant to people who have no religious preference or who identify as spiritual but not religious.

Alternatively, fiddling with the ecclesiastical year might waste too much time and energy. The change, for better or worse, would further distinguish Episcopalians from Roman Catholics and other Western Christians who observe the liturgical year. In any event, the date of Christmas, as well as the length of Advent and Christmas, is unimportant.

The Church too often focuses on adiaphora. I don’t care when Advent starts or how long it lasts. Neither being in nor out of step on those issues communicates clearly and loudly the rhythm of the different drummer to whose beat God calls us to march. So I am very happy to have others, whether ecclesiastical or civic authorities, decide those issues.

Instead, I want to focus on the important stuff, the stuff that really matters to people who are trying to follow the drumbeat of God’s Spirit. I think Pope Francis gets this and that is why so many Roman Catholics experience Francis’ leadership as a breath of fresh air. I sharply disagree with Roman Catholic teachings on many theological and ethical issues; I doubt that Francis will change these teachings. However, he recognizes that in marching to the drumbeat of God’s Spirit the Roman Catholic Church must embody a Christ-like love. His predecessor’s emphasis on rigidly and incessantly proclaiming more contentious Roman Catholic teachings frequently put the Roman Church needlessly and unhelpfully out of step with society. We should try to stay in step with culture unless getting out of step is an unavoidable consequence of marching to the different drumbeat of God’s Spirit.

The next decade seems likely to be critical for The Episcopal Church’s future. We have journeyed through challenging times defined by our increasing commitment to social justice and the full inclusivity of all God’s people within the Church. The move has been costly and Episcopalians increasingly live on society’s margin. Will we slowly fade into oblivion, out of step but not really marching to a different drummer? Alternatively, will we, hearing the drumbeat of God’s Spirit ever more clearly and loudly, move confidently into a new era in which our congregations are centers of life abundant life, radiating God’s light and love, transforming their neighbors and the surrounding communities?

George Clifford is an ethicist and Priest Associate at the Church of the Nativity, Raleigh, NC. He retired from the Navy after serving as a chaplain for twenty-four years, has written Charting a Theological Confluence: Theology and Interfaith Relations and Forging Swords into Plows: A Twenty-First Century Christian Perspective on War, and blogs at Ethical Musings.

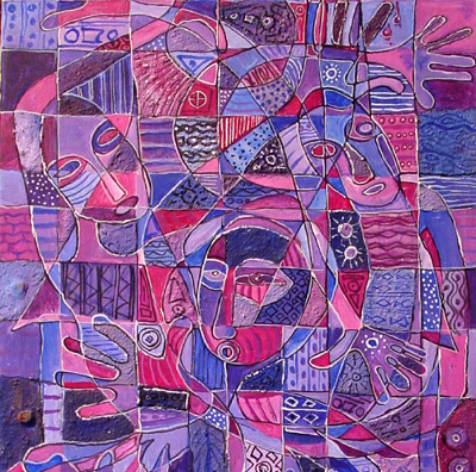

image: Drummer and Dancers (detail) by Nzante Spee, 1995 Source: WikiArt