by Martin Elfert

Near the end of the 1970’s, I had the opportunity to study bullies in their natural habitat. I enrolled in Kindergarten as imaginative and somewhat eccentric child, small and poorly coordinated. Thus, when class let out for recess and I walked out onto our elementary school’s playground, the bullies all turned my direction. I was like a wounded gazelle appearing on the Serengeti.

I quickly realized that a physical response to the bullies’ clenched fists and leering threats was impossible – my thin arms and slow feet made fight and flight equally untenable. And thus I knew that I was going to have to resort to something subtler. Thankfully, I was and am pretty good at subtlety. And I clued in to a strategy pretty fast.

What I came to understand is that bullying is built out of a perverse reciprocity. What is seductive for the bully – what feeds him – is the reaction of his victim to his threats and his taunts: tears, rage, disorientation, and terror are all equally delicious. Deprived of these things, the bully goes hungry. And so I resolved to wage a campaign of starvation.

If you could hop into your time machine and watch me in those days, you would see me not so far from the school’s main entrance, my back against a wall made of brick. Standing between me and freedom is a boy several grades ahead of me, several stone heavier, and several inches taller. With a practiced snarl, he asks me, “Do you want to die, kid?”

Now look from the bully to my face. What you will see a there is not fear or anger or anything else. Rather, what you will see is a remarkable resemblance to the wall behind my back. I had learned how to go totally flat. Inside, my heart might be racing. Inside, I might be ready to throw up. But on the outside, I betrayed nothing, I gave them nothing. Watch now as the bully becomes confused and then frustrated and then exasperated before abandoning me altogether to look for easier prey.

I was proud of being unteaseable, proud of being unbullyable, proud of having found the sling that, even if it didn’t kill Goliath, did turn him away. More than thirty years later, maybe I am a little proud still.

And I suppose that would be the happy end to a hard story of childhood cruelty except for this: when I grew up and bullies stopped being part of my life, I found that the blank mask that I had so carefully learned to hang over my features didn’t want to come off. Sometimes I was – I am – like that brick wall when I don’t need to be. Sometimes I am startled and saddened when a loved one tells me: I had no idea that you were having a good time, I had no idea that you were happy.

About a year ago, I sat with an elder and told him this story, told him about my strategy of blankness and how it has stayed with me for so long, a guest in my home years beyond the invitation that I gave him. And the elder asked me one of those beautiful and simple questions that wise folks sometimes just know to ask: Is that strategy still something that you need?

No. No it isn’t.

I guess that I am telling you all of this near the beginning of Lent, because I wonder if learning how to take off our masks might actually be part of what faith is all about, if loosening the straps on those masks might be a kind of Lenten discipline. Jesus, after all, is the one who refuses to wear a mask. He is the one who is totally present, who is totally vulnerable, to you and to me in our hardship and our joy alike. And, if Thomas à Kempis is right and we are called (however imperfectly) to imitate Christ, then joining him in his vulnerability is part of the task of discipleship.

Your mask may not be like mine, it may not be blank. Yours might feature cynicism or steely resolve or anger. It might feature the smile that you have been ordered to wear so many times. It might features something else. Regardless of what your mask looks like, I wonder what might happen if you took it off for a while. I wonder what might happen if you put down the strategy that has served you so well for so long and looked out at the world with your own tears and laughter. If you looked out at the world, bullies included, with your own unshielded face.

The Rev Martin Elfert has a background in theater and currently serves as the Associate Dean of the Cathedral of St John the Evangelist in Spokane, WA.

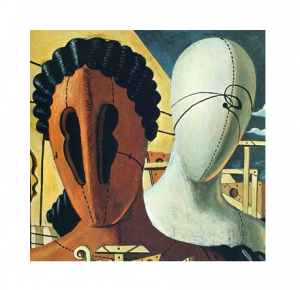

image: the two masks by Giorgio de Chirico