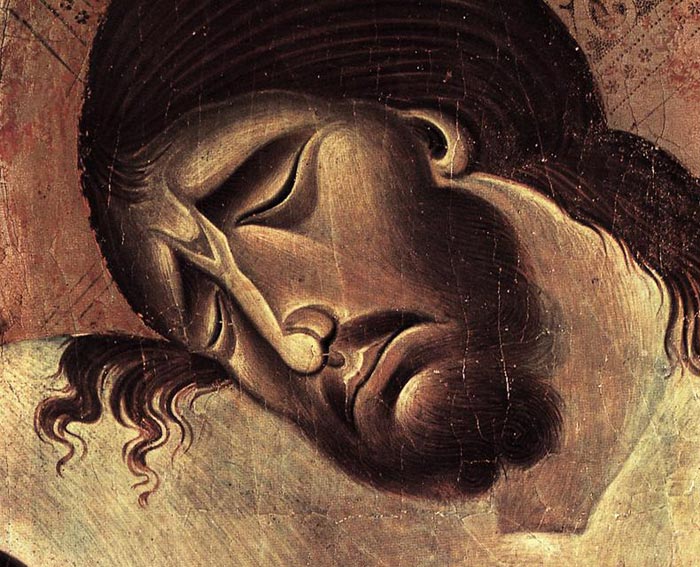

by Carlo Uchello

Why is the day before Easter Sunday called Holy Saturday? On Good Friday, Jesus was crucified and died. He didn’t rise from the dead until Easter Sunday. So, why do we refer to the day in the tomb as Holy Saturday? Why do we say it’s Holy?

Jesus rose on the third day – He was buried on Good Friday before sunset, lay in the tomb all day on Holy Saturday, and rose on Easter Sunday morning. Holy Saturday, then, was the only full day that He lay in the tomb. That, by itself, makes it holy. But is that all?

Holy Saturday is usually one of the most ignored days in Holy Week, and we may tend to view it as merely an unwelcome waiting period – a delay, even – between Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Or maybe we view it as a day to forget about the pain of Good Friday so we can get into the proper, happy mood for Easter Sunday.

What does it have to do with us, anyway? Well, if on Easter Sunday nothing has changed but the calendar, then we have nothing to celebrate and Easter is just like any other day, except for the dyed eggs and the superabundance of candy.

Back to the tomb. What, exactly, was going on in the tomb on Holy Saturday? If we had been there in the tomb, with Jesus, what would we have seen? Did He simply lie there, dead and unmoving, all day and all night on Saturday, and then spring to life instantaneously on Easter Sunday? Or was His resurrection a gradual process, perhaps indiscernible at first, followed by a mild and gentle stirring, as if awakening from a usual night of slumber?

If we had been there with Him in the tomb, what would we have observed on Sunday morning? Would He have slowly begun to move, then gradually sit up? Did He rub His eyes and hold His head in His hands, aching at first with the pain of His crucifixion, His hands and feet and side in agonizing, holy pain?

Popular images of Easter morning show Jesus, radiant, outside the tomb – and sometimes standing with his feet off the ground, as if he had floated out of the tomb, as though the Ascension into heaven had already begun. What were the mechanics of the Resurrection? Did the stone roll, of its own, from the tomb’s opening? And did Jesus then simply walk out of the tomb, where he remained until the women who visited the tomb found the tomb empty, and mistook Him for the gardener? Or was the Resurrection something akin to a bomb going off, with the stone cast aside like a mere tiddly-wink, and Jesus rocketing from the tomb? Or did Jesus simply push back the stone, Himself, and just walk away, matter-of-factly?

If we had been there in the tomb with Jesus, we might have sat next to Him, or across from Him, as the stone was rolled back. But exactly what would we have seen?

Perhaps it is foolish to think about seeing anything. With Jesus dead and in the tomb, the world was in darkness. The forces of evil seemed to have conquered the forces of goodness and light. It appeared that we were meant to spend the rest of our lives in fear. But then Jesus is raised from the dead – and our world is no longer broken and our lives are no longer to be filled with despair.

Our lives are spent in anticipation of resurrection, both in the present life and in the one that is to come. In a way, our entire lives are a kind of a theological purgatory, as we await our own resurrection in Christ. We are stuck in Holy Saturday until we can find our way to the other side.

My own faith journey lay in apparent slumber for 25 years, until one day, 20 years ago, without any fanfare, I awoke to a life in Christ. It isn’t the same for everyone, to be sure. Many people – perhaps most people, I don’t know – are raised in a faith and remain there, more or less, for their entire lives. And I know several people who can point to the exact moment in their lives when they accepted Christ as their Savior. I can’t. Sometimes I wish I could, since it seems so important. But then, when was the exact moment when I became an adult? When did I first become truly aware of the needs of others? When did I first realize that one day, I would die? All of these are important, but I can’t point to a single moment in time when any of these things happened.

But what I know for certain is that over time, in small and indiscernible ways, my heart opened up to Christ and to all humanity in a way that it never had been open before – where though I sometimes fail, I try to accept everyone and everything just as they are. And although it is clearly difficult (and even at times seemingly impossible), with Jesus it is indeed both possible and necessary that we love one another. It is necessary that we accept both good and bad, and those who are still asleep, by praying for them and helping them awake to their own life in Christ. And we have to acknowledge that there are many who will never wake up, and it is our duty as Christians to pray for them anyway. Perhaps extra hard.

Does Jesus stir in the grave? Is His resurrection gradual or instantaneous? Like Jesus, our own Holy Saturday may not follow a gradual, continuous path from slumber to life. There may be movement, both small and large, as well as long periods where it appears that nothing is stirring.

But we can make a choice to work toward emerging from our slumber. The key is love. Love is the animating force that propels us on our journey from Holy Saturday to our own Easter experience – our resurrection in Jesus Christ.

Whether you believe that we are all fallen angels in need of awakening, or whether you simply accept that we need to awaken to our own life’s true calling – our true mission or purpose in life – Holy Saturday can serve as a reminder that we are in need of our own Easter experience. We need to stir from our mortal slumber and find a way to roll back the stone that has blocked us from living our true life and experiencing that which we are meant to be, and that which we are meant to live.

And what is the stone that blocks us from living our true life and experiencing what that which we are meant to be? It’s our lack of awareness – an awareness that we are all interconnected with everyone else. It’s our inability to see, or accept, that we are all members of the Body of Christ. It’s our unwillingness or inability to accept everyone else, especially those people who aren’t like us, people we don’t like, and people who may even mean to hurt us. It’s our eagerness to exclude these people, and to treat them differently. It’s our limited sense of responsibility toward everyone and everything that God created. To put a point on it – it’s our inability to recognize and accept that everyone is a part of God’s creation, no less important than whatever importance we place on our own position in God’s creation. And along with that recognition and acceptance is the realization that we are all responsible for one another, and for building up God’s creation – and that we are to do more than simply not actively work against it. This is the time to recognize that we need to do more than simply avoid sin. We need to seek out goodness. The absence of evil in our lives does not equate to the presence of goodness. That’s not the way it works, and we know it in our heart of hearts. We cannot consider ourselves to be good merely because we believe that we are not as bad as other people. We need to actually be good, and seek and do good things. This is the work that God has given us to do. To love one another. Not in the abstract, writing-a-check kind of way, but in the real, day-to-day encounters we have with all people, and with the people whom we never meet. No exceptions.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus’ last commandment to His disciples is to love one another. And Jesus consorted with tax collectors and prostitutes and the outcast of society, provoking derision and outrage from the religious authorities of His day.

Our yearning for love is the struggle to recover our connectedness to the divine and the eternal. When we love, then, we are attempting to reestablish something of a state of union with the Divine. Our yearning for love is our attempt to regain an immutable oneness with God, who is love personified.

Sometimes an unexpected jolt makes us realize that we’re not in control of what we thought we were, or we realize that what we thought mattered in life really doesn’t. This is especially true when we face an unexpected shock – a devastating diagnosis, the sudden death of someone close to us, or losing a job unexpectedly. When something like this happens to us (and it always does, even if it hasn’t happened yet to you), we may wonder where God is. And sometimes we realize that those all-too-familiar episodes that we call coincidences really aren’t so coincidental, and no other explanation can suffice except for the realization that God is with us. Those moments – sometimes large or small, sometimes painful or life-changing – are all glimpses into God’s presence, and they are gifts. We can choose to ignore or deny these glimpses of God’s presence, and if we do, we make it more and more difficult to recognize them when they recur. But when we accept them gratefully, when we are open to receiving them, we notice these glimpses more and more. We may question whether it is possible or even desirable to live in a state where these glimpses into God’s presence can be sustained. And then, at last, we realize that to sustain these glimpses would be to experience the perfect and complete love of God.

Finally, we come to realize that the only way to really know God is to know love, and to know love we must open our hearts, and not only to those whom we know, but to everyone we encounter, and to those whom we never encounter. When we do that, not only do we know God, but we show our love for Him.

When we feel connected to God, there may come a moment when we feel that we are connected to every living being. When this happens, we finally understand God’s commandment that we love our neighbors, even our enemies. When we can love every living being and see the face of God in our neighbor – every neighbor – we will have entered into the heart and mind and complete love that is God. And when we choose to focus our lives on God, then nothing is an accident. And living in this moment is the Kingdom of God on Earth, or a glimpse into it.

Every time that we reject someone, we reject Jesus, who loved everyone. Every time we return hatred or violence with anything other than love, when we curse our neighbor or demonize other people, we are cursing Jesus, and we are driving more nails into His hands and feet. Every time we enforce old rules or pass new laws that separate us rather than unite us, we are piercing His side all over again. And in doing so, we extend the duration of our own suffering and delay the coming of the Kingdom of God on Earth.

Maybe that is the real reason we call it Holy Saturday. It’s holy because we, too, have a sacred obligation to sanctify our lives for a greater need, something beyond ourselves. Maybe Holy Saturday isn’t about inactivity. Maybe it’s the inner activity that we have to undergo before we, too, can find new life after the crushing defeat of our own crucifixion.

When we love, or even when we open ourselves to the possibility of loving another person, we allow a small opening to appear in the hardened shell of our isolated existence, and we get a glimpse of heaven on earth. Of God’s Kingdom on Earth.

The only force that could have raised Jesus from the dead was love; love was the force that allowed Jesus to raise Lazarus from the grave; so much more love was required for Jesus to rise on Easter Sunday. And love is the only force that can raise us from our own Holy Saturday slumber. Our love of others is required, but it is not enough – we need Jesus to raise us from our own graves of lassitude.

We are born in Christ. We die in Christ. We are with Jesus in the tomb, and it is Holy Saturday, every day.

“God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God, and God in him.” – 1 John 4:16

Carlo Uchello is a member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, where he serves as a Lector/Chalicer and on the Altar Guild. He has previously served on the Adult Education Committee.