Last Monday we posted an item about an interview with famed British comedic actor Stephen Fry “where he is asked a hypothetical question by presenter Gay Byrne. “Suppose it’s all true, and you walk up to the pearly gates, and you are confronted by God. What will Stephen Fry say to him, her, it?”

Fry responds with indignation, stating that he’d criticize God for the natural evils within the world. Fry explains that his atheism is founded not merely on the idea that there is no God, but that if there was a God, he’d be a monstrous and capricious creature.”

Several commenter in the UK have published responses worth looking at. The problem of evil has been a fertile ground of study and speculation in theology for a long as, well… for as long as there’s been theology.

Giles Fraser, writing in the Guardian admits to an admiration of Fry’s honesty in his answer as well as Fry’s willingness to speak truth to power (even a power he doesn’t believe in).

And though I think there is a whopper of a mistaken assumption at the heart of his answer, I nonetheless think it was an admirable one.

Why? Because what Fry was asked was what he would say to God if he met him face to face. And this presumes that God exists. So imagine: Fry is sitting opposite God and telling him that he is a bastard because he invented cancer and insects that burrow into children’s eyes. These things are pinned on God by Fry because God is literally the creator of everything and all-powerful. God could have done something to change the situation, but he chose not to. QED: he is a bastard.

What greater example of speaking truth to power could there be than this? And for absolutely no reward. For if Fry is right about God being an omnipotent bastard, then he could hardly expect to be rewarded for his honest observations. He tells the truth then burns in eternity. In this scenario, Fry is entirely heroic in his truth telling.

Too many religious people actually worship power. They imagine the source of ultimate power, give it a name (God, Allah, Yahweh) etc, and then try and cosy up to it, aligning their interests with those of the boss. In this they are just the same as many non-religious people, except they believe that ultimate power is metaphysically situated. Whether it be a king or a prime minister or a CEO or God: the temptation is always to suck up to power.

Author Madeline Davies also admires Fry’s willingness to answer honestly, suggesting that struggling with the answer is an important part of what it means to live faithfully – to follow Jesus even in the face of contrary evidence; to follow the one whose answer to death is resurrection.

I don’t have the answer to Fry’s question.

But I have rejected his God.

I can’t, and don’t, believe in a God who is “capricious, mean-minded, stupid”.

Neither do I believe in the sort of heaven presented in the film on death produced by the British Humanist Association, which he narrated – a place you hope to scrape into if you’ve done enough good things to merit a reward.

To be fair, Fry was responding to the sort of God given to him by the presenter: the bouncer at the “pearly gates”.

(Incidentally, it was quite funny when this presenter said: “And you think you’re going to get in?”

My personal impression of God post the two-year Bible read is that he has a soft spot for ranters.

I also imagine he found the Speckled Jim episode hilarious.)

So, no, I don’t spend my life cravenly thanking a God who sits on a cloud just watching while we suffer.

The God I believe in is loving, compassionate, present – sometimes through other people – and cries with those who suffer.

“Jesus wept”

posted by Jon White

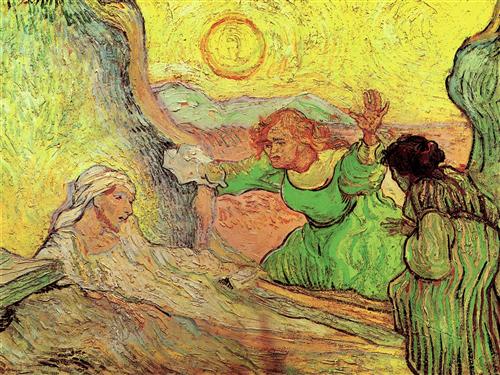

Image: The Raising of Lazarus by Vincent Van Gogh