The Magazine

by The Rev. David Hedges

This Spring I will have been vegetarian for eleven years. I first spent time without eating meat as a Lenten discipline in 1999 or 2000, and it was the first time that I had a Lenten discipline of any note. I loved two things about it. First, there was a certain satisfaction in eating more deliberately and making specific choices rather than simply eating whatever was available or whatever suited my pleasure at the moment. Second, there was that thing which is common to all Lenten disciplines, which is to say an exercise in making choices because of a personal commitment to God.

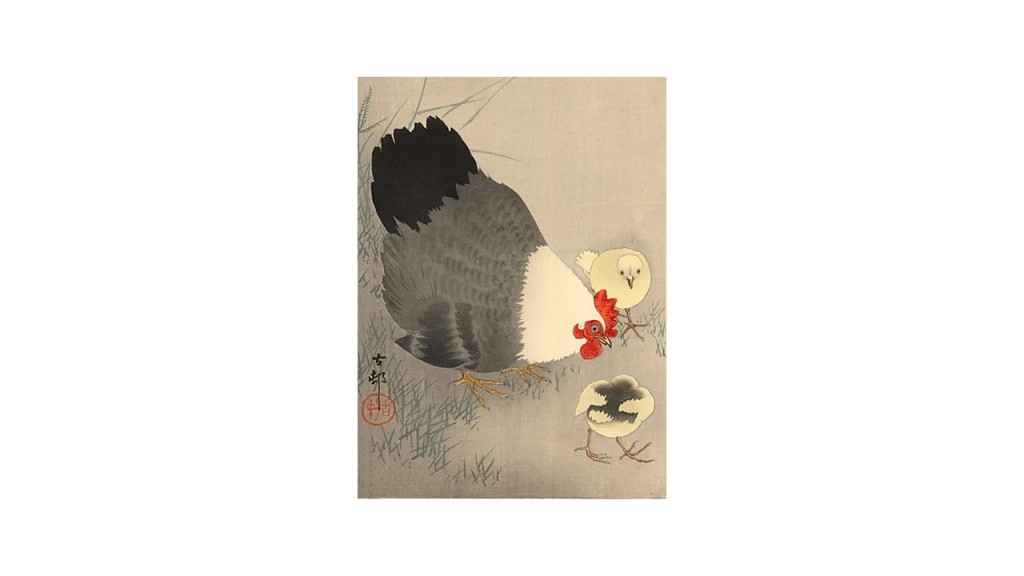

For several years thereafter I continued to go meatless for Lent. But it was in 2004 that I decided to make the plunge and become a committed vegetarian. At the time I was in seminary at Seabury-Western and our ethics class came to the topic of animal rights. Our visiting ethics professor, Trevor Bechtel, a Mennonite ethicist and long-time vegetarian, said something that stuck with me. “Animals don’t need rights,” he said. “Animals need people to stop beating them up.” That made sense to me on a number of levels. But primarily it gave lie to the thing I kept telling myself: I would become a vegetarian but I like meat so much.” Bechtel’s words made me think: What if I had to explain myself to a chicken?

The decision to take the plunge and become vegetarian was sparked by a discussion of concern for the lives of animals. But for several years of appreciating vegetarianism before actually becoming one, the underlying theme was the broader ecological benefit. Livestock raised for meat, and especially cattle, consume prodigious amounts of grain and water, and much of it in the American West, where water use is becoming an ever more contentious issue due to the increase of droughts. Livestock are also a major source of greenhouse gases. As a result of these and other factors, vegetarianism has been said to have the greatest positive impact on the environment of any life choice a person can make. Although I am not vegan (vegans, in addition to eschewing meat, also refrain from consuming dairy products, from wearing wool, leather, fur, and from the use of any animal product) I am quite aware that the environmental benefits of vegetarianism are greatly magnified by practicing veganism. I believe that vegetarianism is therefore one of the most faithful responses to God’s command to Adam in Eden to “till [the earth] and keep it.” (Genesis 2:15)

It was in a closer reading of Genesis, however, that I came to understand vegetarianism not only as an ethical commitment but as one having religious significance for me. In the story of the Garden of Eden, God provides “every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food,” and tells Adam “you may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat.” We all know what happens with that particular tree – but we often ignore the rest of the trees. This plant-based diet is one component of a created order that does not include predation or meat-eating. It is only later in the story of the rainbow covenant after the flood, that God gives humans permission to eat meat (Genesis 9:3-5). While God gives us permission to eat meat, it is not part of the original plan. The Anglican priest and ethicist Andrew Linzey suggests that this permission is a concession to human weakness and violence. Further, when we come to the end of the Bible, the final chapters of the Revelation bring us back to life in a garden: the new Jerusalem descends from heaven to earth and the city and the garden are reconciled. Human civilization and the created order come together by God’s act, and once again people feed on plants, as “On either side of the river is the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, producing its fruit each month.” (Revelation 22:2)

I do not take these biblical images as a literal command to be vegetarian. I do not think the Church can rightly require Christians to be vegetarian, and I prefer to shy way from anything that smacks of a purity code or a list of clean and unclean foods. I have always understood this as my choice, and have striven not to judge those who eat meat. Nothing turns people away from a vegetarian lifestyle like a self-righteous puritan attitude. One of Jesus’ more powerful teachings, after all, is that “it is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person, but what comes out of the mouth that defiles.” (Matthew 15:11) However, from these images we can gain a context for vegetarianism as a personal spiritual practice that is aligned with God’s will for a peaceable kingdom in which violence and predation between creatures does not exist, and in which human society coexists in harmony with the created order of nature.

The Rev. David Hedges is Rector of Saint Peter’s Church in Sycamore, Illinois. He will represent the Diocese of Chicago as a Deputy at the 78th General Convention.