THE MAGAZINE

by Donald Schell

Like many Episcopalians, I grew up in another Christian tradition in a church our family has been part of for over a hundred years. My mother, a retired Presbyterian minister in her early 90’s, now serves that church part-time. But I’m not a clergy kid and her work there is a small miracle.

I’d been an Episcopal priest for a dozen years when mother’s Presbytery generously invited me to join her colleagues helping ordain her in a sweet symmetry with my own ordination where Presbyterians, Lutherans, Jesuits and a rabbi (colleagues in my new work with Yale Religious Ministry) laid their hands atop Bishop Stephen Bayne’s hands as he ordained me. Ecumenically rooted and ordained at the hands of the first Executive Officer of the Anglican Communion I know our Anglican Communion struggles simply come with the territory.

Christian formation and identity for me were shaped not just by difference, but by contradiction and conflict. From my own earliest experience of church community, my family was out of sync with people in our church that we loved. My Presbyterian home congregation leaned toward independent fundamentalist churches in cultivating ecumenical contact. In the years I was growing up there, our pastors identified as evangelical and shunned Presbyterian program materials. Weekly at home I’d grill my mother with questions about what I’d heard in church on Sunday:

Doesn’t God have more purpose in mind for us in this world than witnessing to Christ and converting our neighbors to be Christians just like us?

If you’re teaching adult Bible classes, how can your good friends say women should keep silent in church?

Isn’t evolution true?

Aren’t some Catholics as Christian as we are?

Do you worry about going to hell?

How can people say Negroes are all cursed descendants of Ham when the Noah story isn’t literally true?

Does my Sunday School teacher really believe Martin Luther King is a communist?

Mother always encouraged the questions, and would offer her own questions, and think patiently with me. My dad, a physician and a skeptical and inquisitive scientist, was simply glad to hear I had questions. He summed up his faith by confessing how much he couldn’t claim to know, offering a general reference to things the church said that didn’t make sense to him, and reiterating his lasting debt to C.S. Lewis who had given him a way to live with his uncertainties.

With the most troubling questions (like the Sunday School teacher’s claim that Martin Luther King’s was a communist pretending to be a Christian), I’d ask why we didn’t just find another church. My mother replied, “This is our church family. We don’t agree with everyone here, but we’ve been here as long or longer than anyone else, and faithfulness to church family is part of church for us.”

When mother was elected to session (church council), old friends left the church in protest. More of them left later when the Session voted to sponsor her for ordination. And later again, after she’d retired and returned to serve this congregation, at the Executive Presbyter’s request, mother weathered the storm of the senior pastor trying to take the congregation into schism over the Presbytery’s vote to welcome LGBT ordinands and clergy. Though he was afraid to fire her, the pastor regularly preached that mother was Spirit-defying troublemaker. Yes, I’m proud of her, and mother’s courageous, patient wisdom shapes my response to Canterbury, GAFCON, and the condemning voices among our brothers who are Anglican primates in Africa – so far as we can tell, we’re following the Spirit, so we’ll try to stay in relationship because that’s what we’re called to do.

My own conscious commitment to living with conflict in the loving, freeing work that shapes and forms us began with high school Sunday evenings when I sat through many repetitions of “Just as I am,” stubbornly resisting altar calls as preachers in churches our youth group would visit exhorted us to wonder yet again whether we’d really, truly, and genuinely given our hearts to Christ.

I knew I couldn’t come forward with any integrity. The nascent Episcopalian kept thinking, “Yes, some people do experience a ‘moment of conversion,’ but others of us have an arc of formation that stretches back even before we were born, and now practice shapes us to God. I know Jesus loves me and I’m learning to love as I follow him.” As a priest, I care more for human formation as the Spirit breathes in all that live, and don’t expect everyone can or should have a conversion experience. With Irenaeus of Lyons I trust that the glory of God is a living human being.

Congregational singing shaped me.

Again, some of that shaping was by resistance and protest. Sunday evenings as we sat singing “There is a fountain filled with blood,” “I was sinking deep in sin,” “When the roll is called up Yonder” and “Do Lord,” I’d keep hoping we’d get to sing the gems from that tradition, hymns I still love like “Amazing Grace” and “Marching to Zion.” Singing from tunes from the Geneva Psalter, Bach Chorales, or plainsong treasures like “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” on Sunday mornings stirred hope for connection with the broader and more ancient Christian tradition.

And in my last two years of college, attending a Lutheran Church, singing guided me to the practice of embodied formation in liturgy. Repeatedly singing Regina Frexell’s adapted plainsong settings for Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei, taught me the deep formational power of simple, beautiful texts and tunes.

My wife and I are just now completing an out-loud, reflective read-through of the whole Bible. She, the cradle Episcopalian, struggles wondering, “how all this can be sacred scripture.” Reading it today and loving its mix of inspiration and conflict, judgment, terror, mercy, and love, I’m grateful for years of unexpurgated Bible stories in Sunday School, for weekly recitation of newly memorized individual scriptures, and even for “sword drill,” where the teacher called out a Bible verse and we’d race to be the first to find it, and stand to read it. Sunday School’s uncensored journey through stories from Genesis, Exodus, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, I and II Kings, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Jonah made the book for me family stories with all the wisdom and bafflement, tenderness and unarticulated hurt that old family stories can carry, and yes, the Spirit moves graciously in the mix.

6 p.m. Wednesday night was the moment my family’s stubborn faithfulness to our church made most sense to me, when seventy-five people stood gathered at tables for a spirited singing of Old Hundredth. Then we’d shuffle along the serving table with our plates sampling the feast our moms had cooked at home – prayer in song and feasting. Wednesday potluck shaped me for weekly communion.

After potluck the adults’ Wednesday prayer made less sense to me, so I’m grateful for our Wednesday youth gathering. Our leaders were young couples from BIOLA or Bob Jones University now headed for a Presbyterian seminary and assigned to work with us for a year or two of “Presbyterian retread,” as one of them put it. Our conversations touched my heart. Like me, our youth leaders were struggling to stay grounded in a very personal love for Jesus while opening to the intellectual, social, political, and religious change that swirled round us.

From the gifts and disappointments of the church I grew up in, I’ve found a home in our Episcopal church where I trust we’re invited to receive blessing and nurture, but also to stay and face conflict and confusion together. Tradition and experience teach me that where the Spirit is stirring, wherever something new is emerging, there WILL BE conflict, but if we stay what emerges is communion.

The Rev. Donald Schell, founder of St. Gregory of Nyssa Church in San Francisco, is President of All Saints Company

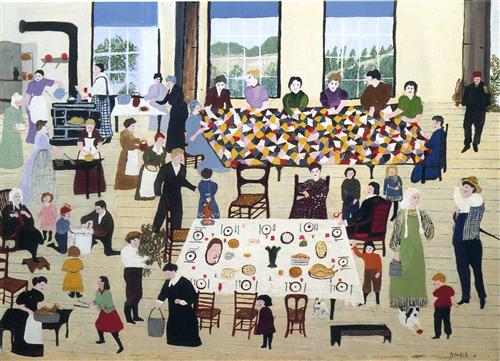

image: The Quilting Bee by Grandma Moses