THE MAGAZINE

by George Clifford

When I was a Navy chaplain, I spent most of my time working with people who did not participate in organized religion. Intriguingly, individuals who considered themselves Christian but who did not attend church often asked me, “Why should I attend worship?” If they were interested, I gave them my answer to their question. Suspecting that those present for worship services attended for various reasons, I occasionally addressed the question in a sermon.

Now, reflecting on three decades of ministry, I realize that my answer to that perennial question changed several times, morphing from a simple we worship because God commands it, citing, e.g., the fourth commandment, to Anglican pastoral vagueness of encouraging individuals to do what is helpful, to offering a fresh perspective on worship.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the noun “worship” as “the feeling or expression of reverence and adoration for a deity.” That definition coheres well with what I learned about worship in seminary, traditional explanations of why Christians should worship, and my answers to the question early in my ministry.

However, I now view that definition of worship as highly problematic. A God who desires – if not demands – human adoration appears grotesquely narcissistic. Such a god seems to be nothing more than a divinized celebrity whose insatiable ego needs prompt ever-more outrageous behaviors to command public attention.

Rethinking worship pushed me intellectually and spiritually to recollect my goals as a priest. In seminary, I read H. Richard Niebuhr’s The Purpose of the Church and its Ministry. His cogent summary of that purpose as the increase of the love of God and neighbor has consistently guided my ministry.

How can (or should) worship increase our love of God and of neighbor?

The answer to the second part of that question, increasing our love for our neighbors, seems more self-evident than the answer to the question’s first part. In communal worship, neighbors – from near or far – gather. Sharing the peace and receiving Holy Communion from broken bread and a common cup are visible signs that we are God’s family. These acts invite us to deepen our relationships with one another. The readings, prayers, and often the sermon emphasize loving one’s neighbor. Even the use of the first person plural in prayers and the Nicene Creed remind us that life is not an individual existence but a communal journey.

Answering the first part of that question, how worship increases love for God, required a significant shift in my thinking about worship. Traditional teachings about worship tend to objectify God, even if that is unintended. This can easily make God seem unreal, the impassive and often unknown object of worshipers’ adoration, praise, etc.

The shift in my thinking was actually subtle and occurred over a number of years. Instead of telling people that they should worship because God commanded it, I realized that I had begun suggesting that people attend worship because it was often the only hour set aside each week in which to think intentionally about God.

Then I started to consider how thinking about God and one’s relationship with God might be a catalyst for an increased love of God. My thoughts kept returning to two verbs: connect and align.

When I love someone, I want to connect with that person. God is omnipresent and wants to connect with me. The barriers to connecting with God are all on my side of the relationship. These barriers may include a lack of desire to connect with God, faults or personality traits believed to prevent one from having a relationship with God, or a lack of attention to God.

Evangelism efforts, including some preaching, often presume a lack of desire to connect with God. Evangelism has earned a deservedly bad reputation for using egoism to try to motivate people to desire a relationship with God. This generally entails proclaiming Christ as the alternative to spending eternity in Hell. That is, one should desire God as a means to satisfy the selfish desire to avoid hell. Manipulation of this type, even if well-intentioned, unhelpfully supplants the moving of the Spirit, for which loving one’s neighbor is often the best catalyst.

Some people imagine that sin is a barrier to having a relationship with God. One may have the hubris to believe that s/he has committed the unpardonable sin or too little self-respect to believe that God can even love her/him. I once had a parishioner who had been an ardent and regular attendee at worship. Then he sinned in some way that he deemed so horrific he could not even summon the courage to name it. He was convinced that if he entered the nave, the roof would collapse and injure everyone present. The good news of the gospel is that God loves us just as we are. Neither sin, pride, narcissism, lack of ego strength, nor anything else diminishes God’s love for us.

Mindfulness training, such as that taught in centering prayer and various forms of meditation, aims to improve attention to God. Widespread western interest in the meditation practices of eastern religions highlights our neglect of this essential element of the Christian tradition. Worship becomes undeniably relevant when it helps attendees to connect with God.

Yet real love entails more than a connection. Illustratively, real love between two people is not hooking up for one night but denotes an ongoing pattern of healthy mutuality. Inevitably, real love changes both of the parties in a relationship.

Christian theologians have historically emphasized God’s immutability. Nevertheless, the Bible repeatedly describes God as having a new or altered thought/intention. One possible explanation, advocated by some process theologians, is that God’s omniscience does not extend into the future. If so, human thoughts, words, and actions may sometimes change God’s thoughts or intentions.

I know (NB: I am certain on this point, whereas less than certain about God) that having a relationship with God changes a person. The more I love God, the more deeply I want to enter into that relationship, the more I want to become like God. This attraction stems from who God is rather than any desire for personal gain or aggrandizement. When I connect with God, I want to align my life in a pattern of ongoing healthy mutuality with God that inevitably changes me.

Conceptualizing worship’s purpose as (1) increasing the love of God by helping people to connect and then to align themselves with God and (2) increasing the love of neighbor has given me a theological framework for understanding the what and how of worship.

Liturgy is not merely a laundry list of activities assembled and sanctified by tradition or personal preference. Instead, good liturgy invites people to gather, to seek intentionally to connect and to align their lives with the one who is life itself, to enter more deeply into a community that seeks to incarnate that life on earth, and then to go into the world to love God and neighbor more fully.

Worship’s two-fold purpose also contextually guides my liturgical choices within the penumbra of that branch of God’s family in which I live and minister, the Episcopal Church: rites, forms, manual acts, music, homiletic moves, etc.

Most importantly, I have what I believe is a credible and comprehensible twenty-first century answer to the perennial question, “Why should I worship?” My answer no longer depends upon guilt to motivate attendance (God said to attend implies one should feel guilty when absent) nor idiosyncratic personal preference (make the sign of the cross or kneel as seems helpful). Worship is an opportunity to connect with the mystery that we name God, more fully align one’s life with the one who is life itself, and to grow in love for one’s neighbor.

George Clifford is an ethicist and retired priest in Honolulu, HI. He served as a Navy chaplain for twenty-four years, recently authored Just Counterterrorism, and blogs at Ethical Musings.

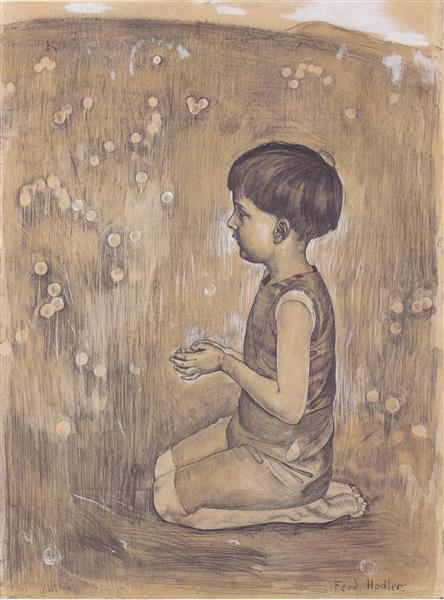

image: Worship by Ferdinand Hodler